It’s Wednesday, Oct. 12, and I’m at the Loony Bin Comedy Club in Oklahoma City. Terri and Larry, the club’s owners, have collected a killer’s row of local talent for the first show of the club’s final week of business.

“You guys seem somber,” Terri tells our assembled group with concern in her voice. “I don’t want you to be sad.”

She’s usually so stern.

I can’t believe this is the same woman who dissuaded me from saying “goddamn it” on her stage 15 years ago.

It’s true. We are much quieter than usual. I think we are just trying to take it all in.

For 20 years, the Loony Bin has been a home for standup comedy in Oklahoma City, running six or seven shows a week. I’ve seen more bachelorette parties, bar fights and comedy sets done on a dare at this club than I ever wanted to see. Still, this place has also held its fair share of dreams.

After Saturday, it will be gone.

The Wednesday show is sold out, and after our brief meeting, many familiar faces — regulars from throughout the years — start to pour in. They flash me smiles as they walk by. Their recognition and anticipation energize me. I can’t wait to perform.

This is our night. Tomorrow, a touring comedian, William Lee Martin, will take over for the remainder of the week. It dawns on me that he will be the last comic to perform on this stage.

“Is William Lee Martin the same as Cowboy Bill Martin?” I ask my friend. “I opened for Cowboy Bill Martin more than a decade ago. It was one of my first weeks working here.”

“It’s the same one,” my friend replies.

“Why isn’t he a cowboy anymore?”

“He’s still a cowboy. It’s just tacky to call yourself a cowboy now.”

“It is?” I shrug. “Times change, I guess.”

Remembering the early days

It’s 2009, and the early Friday show is letting out.

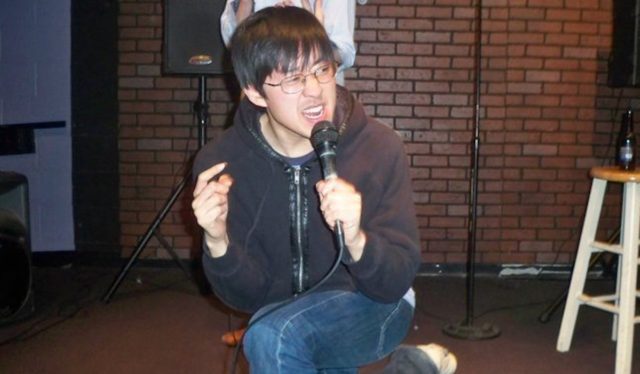

Brooding inside a cloud of second-hand smoke, I’m hiding behind another comedian’s merchandise table. I’m up against a brick wall in more ways than one.

Two touring comedians are coaxing drunk audience members into impulse buys that they won’t remember in the morning. I’m using the pair as meat shields to block death stares from exiting audience members — parting shots to remind me that I do, in fact, suck at comedy.

It’s my first week getting paid for standup, an opportunity I’ve slogged toward for two years. Prior to my first show, I had envisioned outperforming the headliner all week on my way to an abrupt sitcom deal with NBC.

Things haven’t gone as planned.

It’s my fifth show, and my sets — as well as the audience’s meek reaction to them — have steadily declined throughout the week.

Every performance feels like a bad date: Now that I’m here, I have to keep talking, even if everyone would rather I stop.

From my shelter behind the merch table, I peek out to look at the clock. I have another bad date in 30 minutes, but I’ve barely started to process the last one.

I attempt to wear this latest failure as a badge of honor. I remind myself of the famous video of Bill Burr where, during a disastrous show in Philadelphia, Burr puffs out his chest and berates the crowd for 11 minutes. With a feverish, hateful, improvised rant, Burr beats back a wave of criticism through sheer will.

In truth, my night’s more depressing than heroic. Yelling at people who don’t like my jokes isn’t appealing to me. Also, I’m not Bill Burr. People won’t romanticize the time a no-name comedian in Oklahoma City shouted at them for his entire set.

Whether I like it or not, I have to sit in this moment until it gets better or I do. I need to get over it.

In an effort to be optimistic, I decide to stop hiding and go stand with the other comics as they chat with departing audience members. Perhaps there’s someone in this procession who actually enjoyed my set, I tell myself.

I keep staring at the clock as clusters of people continue to walk by, thanking the other performers and shaking their hands. After a while, it’s apparent no one is coming to talk to me.

Just as I’m about to give up and head to the bar for another quick drink before the next show, I notice two women asking the other comedians to sign their breasts.

Both of the other comedians do as they’re instructed, and I stare into the middle distance.

“Hey, you,” I hear one of the women call to me. “You can sign our boobs, too.”

“Really?” I say with the surprised excitement of a child who is finally picked in a gym-class basketball game.

They hand me a Sharpie, and I scrawl “James Nghiem” before they can change their minds.

Their request, which feels like a merciful gesture, begins to change my night and my mood.

“It was a great show,” one of them says. “We got tickets to the next show, too. You did great.”

“You bought tickets to the late show, too?” I ask. I’ve never seen anyone buy tickets to the same show two times in one night.

“Yep,” she says.

“I’m just going to say the same jokes again. Are you sure?”

“That’s OK. It was so good. We want to see it again.”

“Thank you,” I say.

After some time, the women return to the show room to grab their seats. Funk music plays, and the DJ beckons me to the stage one more time.

Filled with confidence, I promptly bomb again, this time with two women who are wearing my signature sitting at the front table next to the stage.

Cheers to time spent

I blink and it’s 2022 again. Years have passed since that night, and I’ve never been asked to sign another breast. Maybe a more optimistic perspective is that I stopped performing terribly enough to warrant such pity.

For a moment, I think about all the strange things and personalities I have encountered in this building and wonder what I’ll see tonight.

Cheers to time spent, and to old, ugly scars that sometimes heal into interesting, attractive shapes on our skin — conversation starters for friends we haven’t met yet.