(Update: As part of its Fiscal Year 2024 budget agreement, the Oklahoma Legislature approved a $96 million appropriation increase to the University Hospitals Authority in support of OU Health’s provision of otherwise uncompensated indigent care. The following article remains in its original form.)

A massive $1 billion debt load and another bond downgrade have combined with pandemic-related revenue loss and higher staff salaries to create a precarious financial position for OU Health, the state-supported hospital enterprise that partners with the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the OU College of Medicine to operate a fully integrated academic health system.

Created following a controversial 2021 merger and the $850 million 2018 buyout of a private hospital management company, OU Health operates the flagship enterprises of the OU hospital system, including the Oklahoma Medical Center, the Children’s Hospital, the Stephenson Cancer Center, the Harold Hamm Diabetes Center and the Edmond Medical Center. OU Health also includes the state’s only Level 1 trauma center.

Although the conflation of state and private resources and governing boards can be exceptionally confusing, state leaders uniformly view the OU Health enterprise as too important to fail — an incomparable intersection of Oklahoma’s highest-quality health care services, its largest medical education system, and the state’s social safety net.

“This is a state asset. It’s not like an ordinary hospital. It provides care that is not available anywhere else,” said OU President Joe Harroz, who also serves on the private OU Health governance board. “I think we’re going to find a path. Here’s the thing: We have to for the sake of our state, and we will.”

While OU Health officials declined to be interviewed for this story, leaders of the Oklahoma Legislature have acknowledged their concern about the health system’s financial picture, which includes a mountain of bond debt, covenant breach risks, a quiet loan from the OU Foundation, and a new operating plan for 2023. Vaguely described in press releases and public meetings, that plan involves staff reductions, increased patient quotas and other efforts to save and raise money.

The situation has stressed university officials, generating long hours of private meetings and delicate relations with legislative leaders, who have requested direct updates about OU Health’s plan to avoid bond defaults and build 45 days of operational cash onto the balance sheet.

In late January, House Speaker Charles McCall said OU Health is facing “real challenges” and may ultimately request additional financial assistance from the Legislature.

“It seems like that would be a logical assumption,” said McCall (R-Atoka). “[We are] going to want to know that OU has taken the necessary steps to right-size the situation, know how they are going to address their debt obligations and present a plan to the Legislature before the Legislature is going to consider that.”

Budget chairman: ‘Nobody likes surprises’

Whether lawmakers will need to appropriate millions of additional dollars through the University Hospitals Authority and Trust to support OU Health remains to be seen, but legislative budget leaders want a clear idea sooner than later.

“Nobody likes surprises. They assured me that they had a plan. They showed me the plan [in December] and by the beginning of the fiscal year July 1 they should be where they need to be on the daily cash on hand for days of operation — over 45 (days),” said House Appropriations and Budget Committee Chairman Kevin Wallace (R-Wellston).

Wallace said OU Health’s problems stem from a “perfect storm” and “terrible timing,” wherein the $825 million buyout of a private hospital operating company was compounded two years later by the pandemic-related economic disruption that hit American hospitals in 2020.

Months after hiring Dr. Richard Lofgren as CEO in February 2022, OU Health took out $150 million of additional obligations in an effort to improve liquidity, make operational investments and rectify the organization’s capitalization concern. But with debt repayments and sagging revenues challenging OU Health’s balance sheet, the organization ended 2022 by laying off about 100 employees and setting new patient-load obligations for physicians who teach at the OU College of Medicine.

As the state’s new fiscal year approaches July 1, OU’s Health challenges have spurred other creative conversations about financial options.

“From what I understand, there have been conversations with the Health Care Authority about bailing them out. And I sent the word, ‘Do not do that,'” Wallace said. “If that’s going to happen, they need to come here. We need to run legislation and direct those funds to be utilized that way by the Legislature, not the secretary of health.”

Underscoring the complicated relationships among state, private and quasi-government health care entities that operate on the hospital complex south of the State Capitol, Health Care Authority executive director Kevin Corbett is also Gov. Kevin Stitt’s Cabinet secretary of health, and he holds a seat on the five-member governing boards of the University Hospitals Authority and Trust.

Gary Raskob, who is employed as the interim senior vice president and provost for the OU Health Sciences Center, also serves on the UHAT boards, which oversee some funding that benefits OUHSC.

With ‘junk’ rating, OU Health carrying more than $1 billion in debt

OU Health ended its 2022 fiscal year carrying at least $1.3 billion in debt, according to a December report from the bond rating agency Moody’s, which downgraded OU Health’s rating to Ba3, a level generally considered “junk” or below investment grade. Bond rating downgrades make it more difficult and expensive to borrow additional money.

Moody’s said the December downgrade “reflects the likelihood that [OU Health’s] cashflow will continue to be well below historical levels and expectations, which will contribute to further declines in an already weak liquidity position and increase the risk of a covenant breach,” a violation of lender-borrower agreements that can carry legal, compensatory or bond-rating ramifications.

Moody’s forecasted a “negative” outlook for existing OU Health bonds, which “reflects risks that cashflow in fiscal year 2023 will be materially less than budget and the system will require sizable external financing assistance.”

Senate Appropriations and Budget Committee Chairman Roger Thompson said the situation bears watching.

University Hospitals

Authority & TrustThe Authority (UHA) was founded in 1993 and originally had over 4,000 state employees managing the day-to-day operations of the University Hospitals. In 1997, the UHA Board proposed the privatization of the hospitals’ management to the Legislature and governor.

Legislation was enacted to privatize the operations of the hospitals under the University Hospitals Trust (UHT). UHT entered into a joint operating agreement with a private hospital management company (HCA Health Services of Oklahoma) on Feb. 7, 1998. The employees of UHA were transitioned to employment with the private company on Feb. 8, 1998. UHA has zero employees today.

On Feb. 1, 2018, UHT entered into a new joint operating agreement with an Oklahoma based 501(C)3 to manage the hospitals OU Medicine Inc. (DBA OU Health).

Source: UHAT

“I’m concerned about it. I’m not alarmed, but I’m concerned,” Thompson (R-Okemah) said in January. “I have met with them. I will continue to meet with them. I feel confident in their plan moving forward that they’re going to pull out of this. But to say that it is not concerning is not an accurate statement.”

Wallace said that between January and March, UHAT revised its official budget request for FY 2024, which had originally included only $7.5 million of new funding. Now, UHAT’s request is for $23.7 million in new appropriations.

OU Health officials have said little about their requests and goals, declining to be interviewed about the critical state hospital system’s finances and business plans.

But during an OU Board of Regents on Tuesday, new board Chairwoman Natalie Shirley said regents discussed OU Health problems during a private committee meeting and executive session. Shirley had been the regents’ designated appointee on the private OU Health board since January, but regent Bob Ross will now fill that role.

“As we have advised this board and the public before, there are certainly issues that OU Health is working through, but they have a tremendous team in place that I know will address the financial and organizational issues that are presented to them,” Shirley said in the public meeting.

In January, Thompson said he and OU Health leaders had not discussed additional state funding through the University Hospitals Authority and Trust.

Thompson said he must “understand all the numbers” and that his next meeting with OU Health officials will let him “sit down and go over the entirety of their books.”

The “numbers” on OU Health’s ledger are not entirely clear, but three major debt instruments have been publicly chronicled:

- A 2018 bond series ultimately totaling $1.16 billion that featured initial use estimates of up to $30 million for proton beam equipment, up to $400 million for hospital tower construction and up to $825 million for the buyout of HCA Healthcare, a prominent hospital-management company that had operated the OU hospital system since the late 1990s;

- A 2022 bonded loan for $50 million from Bank of America Public Capital Corporation that is secured by equipment owned by OU Health;

- A 2022 bond series totaling $100 million that is backed by the revenues of OU Health.

Additionally, an official with the OU Foundation recently confirmed to NonDoc that OU Health took out a loan from the university’s private fundraising arm sometime around the 2018 buyout of HCA Healthcare. Another official with knowledge of the situation also confirmed that the loan exists.

However, no one with OU, OU Health, OU Foundation or UHAT has been willing to provide details about the debt OU Health owes to the OU Foundation. As a result, it is unclear whether OU Health has met all of its payment obligations on that debt in recent years.

Wallace, the House budget chairman, said he has never heard of OU Health’s loan from the OU Foundation.

“I’m not aware of their contractual agreements,” Wallace said.

The Oklahoma Development Finance Authority, which has acted as a conduit for issuance of OU Health bond debt, provided a breakdown of OU Health’s repayment obligations for the $1.3 billion in bonds over the coming years:

Loading...

Loading...

‘We have some challenges in front of us’

If the OU Health situation sounds particularly dire in the short-term, that’s because it is, at least according to the public officials interviewed for this story.

“I’m confident we have an excellent team in place, but it’s going to take awhile,” OU Board of Regents member Frank Keating said in January while he was still chairman. “Obviously, the financial challenges are very real. The new leadership and the new structure needs to work, and I’m confident that is the case. We’ve gone out — certainly Joe Harroz has gone out — to find the best and the brightest for the purpose of providing these kinds of needs.”

Harroz said the 2018 buyout of HCA Healthcare was intended to allow OU to control its own destiny and long-term investments regarding the health system, and he said the reconfiguration of health administrators “was absolutely critical to have the modern kind of structure that can be successful.”

“There was not a way for OU Health to be successful the way it was structured. It was an anachronistic structure. It’s not how — not just academic health systems — but how any health system can really function. It was broken up. OU was in charge of the ambulatory piece, and the hospital had the piece over there. You had department chairs that were running their piece,” Harroz said. “You had basically four co-CEOs and multiple boards, and you can’t run an efficient operation and you can’t deliver — more importantly — patient care in a way that is efficient.”

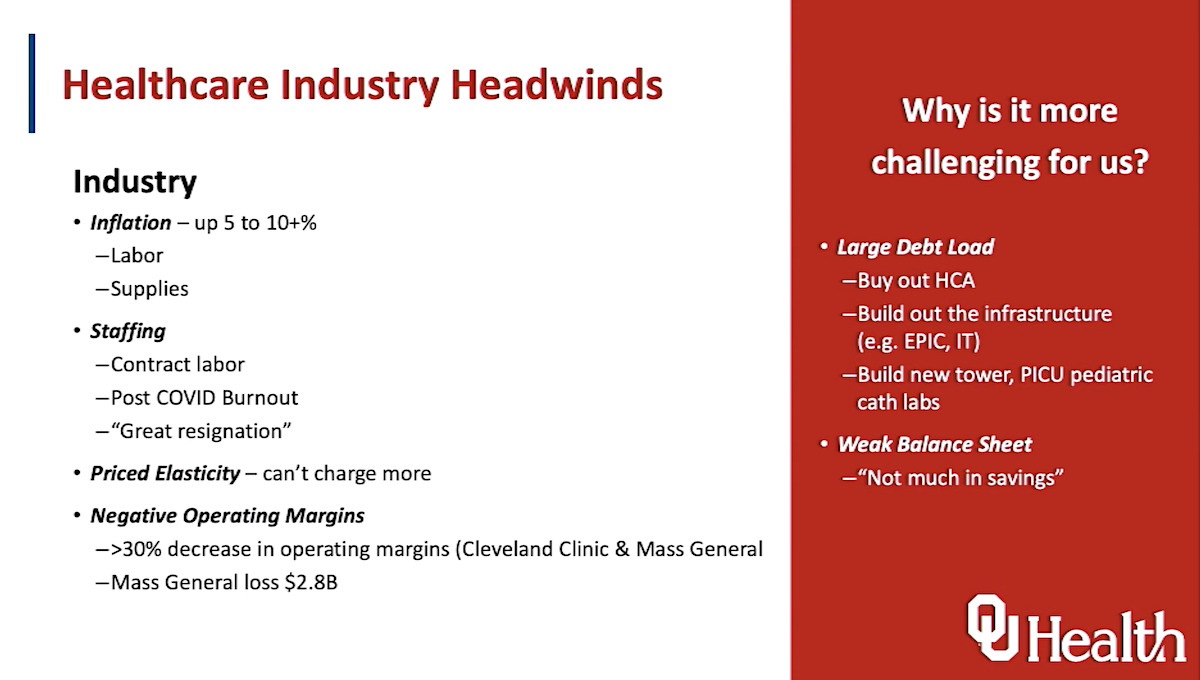

On Jan. 17, OU Health CEO Dr. Richard Lofgren outlined those efficiencies and briefly discussed the organization’s challenges during a 30-minute presentation to the Downtown OKC Rotary Club 29. Lofgren, who came to Oklahoma from UC Health in Cincinnati, said he was “well aware of the headwinds within the organization” when he took his new job.

“Coming into the pandemic as a start up (…) we didn’t have a particularly strong balance sheet to start that. So we do recognize that we have some challenges in front of us,” Lofgren said. “But I will tell you and leave you with the fact that I am incredibly optimistic. Optimistic about health care, optimistic about OU Health in particular. And why am I? It’s because of the mission. It’s because what we do matters.”

To that end, Lofgren noted a few vital statistics of the OU Health enterprise:

- More than 1,000 credentialed providers;

- About 600 residents in training;

- Community access to 74 subspecialties of care;

- About 6,700 Oklahomans transferred to OU Health each year for specialized services;

- About 575 ongoing clinical trials.

“We need to be at the forefront of really addressing the issues of health disparities,” Lofgren said.

But Lofgren emphasized that the 2018 buyout of HCA was followed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has strained the nation’s entire health care system. He noted that even the largest health care enterprises, such as Massachusetts General Hospital and the Cleveland Clinic, reported significant financial loses in 2022.

“The biggest issue we have facing us is really around inflation,” he said. “Our labor costs are up. Our supply costs are up in our institutions anywhere between 5 and 15 percent. We have a whole host of staffing issues as well. (…) There is a significant shortage.”

He said the hospital industry as a whole lacks “price elasticity,” which limits the ability to increase revenue through patient care.

“Apparently my suppliers can increase the prices, but I don’t actually have the luxury to do the same. Now, to be honest, looking at this audience alike, most of you all, you think we’re overpaid. Health care is already pretty expensive. We don’t really have an ability to pass that along,” Lofgren said. “Despite how expensive (…) and how big we are, we’re an industry that operates on pretty thin margins. So that this increase in the supply and labor costs and an inability to move our prices really does make it very challenging for all of us.”

Patti Davis, president of the Oklahoma Hospital Association, said her organization has contracted with a group called Kaufman Hall to analyze the fiscal situation facing all of Oklahoma’s hospitals.

“Hospitals have not rallied from the financial losses due to the pandemic even with federal assistance in surges one and two,” Davis said in a statement. “Federal assistance was not available for surge three and there is no indication that additional federal funding will be coming to hospitals. In Oklahoma, nearly 74 percent of hospitals had negative operating margins in 2022.”

Speaking after an OU Board of Regents meeting in January, regent Rick Nagel made similar observations about the industry.

“Everything about OU Health is getting attention, first of all because of the financial pressures that the entire system in the United States is under right now,” Nagel said. “To the extent that misery loves company, there aren’t really any health systems in America making any money right now. It’s a combination of all the obvious stuff: labor shortages, you’re not able to work with the same kind of patient load; the ones you are caring for are more expensive to treat.”

Nagel noted that the OU Health operating agreement with UHAT requires two annual payments of $20 million each from OU Health to the state, for a total of $40 million per year. At the Feb. 27 UHAT board meetings, members discussed SB 330, by Senate Floor Leader Greg McCortney (R-Ada) and Rep. Marcus McEntire (R-Duncan), which would allow UHAT to increase the required payments from OU Health without legislative approval of a modified operating agreement.

“As a function of the merger, there’s a contractual schedule on those payments. It’s not a question to us on being worrisome today. But as we look down line, we’ve got inflationary pressures everywhere, including the cost of our own professors,” Nagel said. “It’s been publicized, we’ve got a lot of debt.”