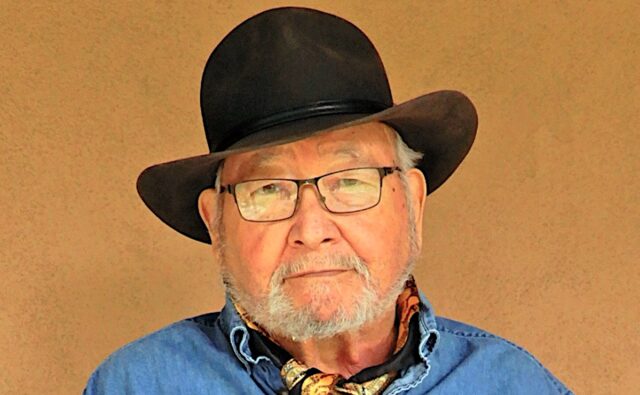

MOUNTAIN VIEW — N. Scott Momaday, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and scholar, had a special place in his heart for Kiowa County. He spent his early life there, and although his family moved out of state and his studies and career kept him away, he held onto a 40-acre tract of land that had been in his family for generations. The land was just a few miles northeast of Rainy Mountain, which became the focus of his second book.

All indications were that Momaday planned to hold onto the piece of property his entire life. But when he died Jan. 24 at the age of 89 in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the 40-acre Kiowa County property had a different owner.

In June 2022, the land was sold for $40,000, but not by Momaday or his daughter, Jill. Instead, the sale occurred during a public auction for failure to pay property taxes, and Jill Momaday said the family knew nothing about it. By the time she discovered what had transpired, the historic Momaday allotment was someone else’s. When another deadline was missed, it became too late even to claim money from the sale, about $39,339.37 after taxes and penalties were paid.

“My dad’s land has been taken without his knowledge,” Jill Momaday said Nov. 30, two months before her father died. “He didn’t get a penny for it. We knew nothing about it. He’s an elder. He’s 89. He’s been sick. He’s had COVID. It’s just horrific.”

In all, the complicated situation unfolded thanks to missed property tax payments of roughly $600, limitations in the state’s antiquated “legal newspaper” notice process and the coronavirus pandemic. Along the way, it has sparked criticism of the longest-serving elected official in Oklahoma, triggered traumas about lost land among citizens of the Kiowa Tribe, and stirred confusion about a cell phone tower that looks over Rainy Mountain, a sacred site for the Indigenous community where “loneliness is an aspect of the land.”

‘I do everything I do for everybody the same’

When she learned about the land sale in late 2022, Jill Momaday was aghast that Kiowa County officials had not done more to track down her father, who had moved to a different house in Santa Fe where the tax statements had not been forwarded. She said he also had contracted COVID in 2020 and was in failing health the last years of his life.

But paying property taxes on time is a burden that falls on a landowner, and Kiowa County Treasurer Deanna Miller said no tax payment was made by Momaday from 2018 until the county auction in 2022. His name was included in a legal notice published in 2019, which started the process of putting the land up for auction if property taxes went unpaid for the next three years as well. Miller said she followed state law and treated Momaday’s situation the same as she did others who failed to pay their property taxes.

“I do everything I do for everybody the same,” Miller said.

Jill Momaday said her father had leased the property for about 20 years to a neighbor who farmed the land. When she discovered the person who purchased her father’s land at auction was the son of the man who had leased it for years, she grew even more frustrated. Then, she heard stories that a cell phone tower had been erected a few months after her father’s land had been sold. Cell companies usually pay landowners to place towers on their land through a monthly fee, which typically increases the value of the property.

Had her father, a tribal member living out of state and in declining health, been taken advantage of?

“It’s very difficult to know what’s going on when you’re not there,” said Jill Momaday, who lives in Santa Fe.

‘The hardest weather in the world was there’

When he died Jan. 24, N. Scott Momaday had lost the land he kept so much in his heart and in his imagination. The neighboring Rainy Mountain, a rounded hill standing near Gotebo apart from the main Wichita Mountains, served as a prominent landmark for Indigenous people on the southern plains.

Momaday described Rainy Mountain with the introduction of his 1969 book, The Way to Rainy Mountain, in which he described confronting his Kiowa heritage during a pilgrimage to the grave of his grandmother that followed the same route of his forebears:

A single knoll rises out of the plain in Oklahoma, north and west of the Wichita Range. For my people, the Kiowas, it is an old landmark, and they gave it the name Rainy Mountain. The hardest weather in the world is there. Winter brings blizzards, hot tornadic winds arise in the spring, and in summer the prairie is an anvil’s edge. The grass turns brittle and brown, and it cracks beneath your feet. There are green belts along the rivers and creeks, linear groves of hickory and pecan, willow and witch hazel.

At a distance in July or August the steaming foliage seems almost to writhe in fire. Great green and yellow grasshoppers are everywhere in the tall grass, popping up like corn to sting the flesh, and tortoises crawl about on the red earth, going nowhere in the plenty of time. Loneliness is an aspect of the land. All things in the plain are isolated; there is no confusion of objects in the eye, but one hill or one tree or one man. To look upon that landscape in the early morning, with the sun at your back, is to lose the sense of proportion. Your imagination comes to life, and this, you think, is where Creation was begun.

In 1934, N. Scott Momaday was born at a U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs hospital in Lawton. His parents and grandmother lived at the homestead near Mountain View. About a year later, his family moved to Arizona, where his parents became teachers on a reservation.

They moved to New Mexico when he was 12. He graduated in 1958 with a bachelor of arts in English from the University of New Mexico, and he earned a doctorate in English literature from Stanford University. His novel House Made of Dawn was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1969, making him the first Native American to win a Pulitzer Prize. In 2007, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President George W. Bush.

Momaday’s tract of land in Kiowa County was close to where he spent the first year of his life, and it was near the location of Rainy Mountain. He leased the parcel to a neighbor, Randy Holsted. Their conversations occurred over the phone, and Holsted mailed his annual lease payment, Jill Momaday said.

Her father’s health began deteriorating in his 80s. He began using a wheelchair in 2017, and he contracted COVID in 2020, which Jill Momaday said developed into long COVID. He moved in 2021 from his longtime residence in Santa Fe to a different house in that city, and apparently the mail was not forwarded.

“I really do place some blame on both those things (the pandemic and mail disruptions) happening, that these were really unusual circumstances,” Jim Momaday told NonDoc on Feb. 16. “It wasn’t just an elder that wasn’t paying attention to his mail or her mail because of being an elder and being just inundated with health stuff or whatever happens. The circumstances were even more than that because of COVID and everything being shut down and my dad being sick.”

‘I thought he died’

Even before the pandemic, however, Momaday had failed to pay property taxes on the land. Kiowa County records show that, in 2016, N. Scott Momaday paid $116 by check for his property taxes and $46.37 for penalties. In 2017, he paid $117 by check.

Then the checks from him stopped, according to Kiowa County tax records.

His $104 property tax bill went unpaid in 2018, and Miller, the county treasurer, said she listed his property along with those of hundreds of others who failed to pay their taxes in a legal notice published Aug. 29 and Sept. 5, 2019, in the Kiowa County Democrat, a legal newspaper in the county seat of Hobart. While legal newspapers are defined in state law, no requirement exists that public information mandated for publication — such as tax records, county auctions and property liens — be placed online in front of a paywall.

In Momaday’s case, notices were mailed to an address in Santa Fe, but no taxes were paid on his property for 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, records show. Taxes totaled $114 in 2019, $113 in 2020 and $111 in 2021.

“We didn’t have a good address, everything kept coming back,” Miller told NonDoc on Nov. 6 after a meeting of the Kiowa County Board of Commissioners. “We sent it out certified mail, and the certified mail was returned.”

State law, Title 68, Article 31, Section 3105, requires county treasurers to conduct a public auction called a tax resale on properties where taxes have been unpaid for three years or more. The resale is to be held on the second Monday of June.

Records, which took Kiowa County officials nearly two months to produce, show Miller placed an advertisement listing properties for the 2022 tax resale auction in the May 5, 12, 19 and 26 issues of the Hobart Democrat-Chief. The ad said the sale would be held at 9 a.m. June 13 in the Kiowa County Treasurer’s Office. More than 60 properties were up for sale, Miller said.

Miller also sent a letter by certified mail to the New Mexico address on file stating that Momaday’s property was to be sold in the tax resale on June 13 because taxes were due between 2018 and 2021 totaling $442. If paid by May 5, 2022, penalties and fees brought the total owed to $623.99, which was subject to increase weekly.

When the June 13 resale occurred, Momaday’s 40 acres were sold for $40,000 to Shakota Holsted, Randy Holsted’s son. After the taxes and penalties were paid, the balance of the sale stood at $39,339.37. Citing Title 68, Article 31, Section 3131 of state law, Miller said Momaday had up to one year after the sale to claim the proceeds. After one year, the money would be placed in the county resale property fund.

After the resale, Miller’s office sent another letter to the Santa Fe address on file for Momaday informing him the property had been sold and that the money, minus the amount owed for back property taxes, was being held in an account by the Kiowa County Treasurer’s Office. The letter said he had one year to claim the money.

“I don’t know what happened,” Miller said. “We did everything. I thought he died. We did everything we possibly could do.”

Miller has worked in the Kiowa County Treasurer’s Office for 45 years. She was elected treasurer in 1986 and is believed to be the longest-serving elected official in Oklahoma.

Miller said she notifies taxpayers by regular, first-class mail each year with a statement of taxes due, which is mailed to each landowner’s last known address. Prior to a piece of property being sold at public auction, she places legal notices in newspapers and also sends a notice through certified mail.

When a tax bill is returned, Miller said her staff uses the online FastPeopleSearch site in an effort to obtain a valid mailing address. She said they also check with other county offices for a valid mailing address, she said.

“I’m just doing my job,” Miller said Jan. 4. “The one they need to investigate is the person who didn’t pay taxes for four years. I don’t understand this. I’ve been here 45 years, and this is the first time this has ever happened.”

Miller’s office also provides the tax rolls online for the general public, she said, and the taxes can be paid online.

“We do every step we can. We do go above and beyond, because I speak with other treasurers, and they don’t even do all that we do to try to find somebody,” Miller said. “It’s the duty and the responsibility of each taxpayer to pay his or her taxes. We don’t want to sell people’s property. We just don’t.”

April Caughern, president of the County Treasurers Association of Oklahoma, said some treasurers do more than the minimum requirement of mailing tax statements to property owners as required by state law, but they are not obligated to do so.

Caughren, who is treasurer of LeFlore County, said she has her staff post a notice on the property either on a house, building or tree if a tax statement is returned in the mail or if the county doesn’t receive payment for property taxes.

“None of that is in state statute,” she said. “That’s kind of an extra step.”

The final burden rests with the taxpayer, she said.

“If you don’t receive a tax statement, that doesn’t mean that the taxes aren’t still due,” Caughern said. “That doesn’t negate the obligation to pay your property taxes.”

‘Scrambling around trying to figure all this stuff out’

A few months after the June 2022 sale, Jill Momaday received a call from a relative who had seen her father’s name in a legal notice in the Mountain View newspaper. The notice involved a court filing by Shakota Holsted in which he sought to be declared the legal owner of the property because neither N. Scott Momaday nor his family could be located to transfer the property. On Nov. 17, 2022, a judge ruled in Shakota Holsted’s favor.

“I told my dad, and he was extremely upset,” Jill Momaday said.

In the months that followed, she tried to find out what had happened. Unfamiliar with Oklahoma laws, she started looking for answers on the state level. She contacted the Unclaimed Property Fund in the State Treasurer’s Office in May 2023 and was told her father’s name came up on the list of unclaimed property. But she said office staff told her they couldn’t determine the amount of the value until after she filled out a claim. She was directed to the treasurer’s office website, but she had trouble downloading the forms, she said. She asked that the forms be sent to her. She mailed the forms back by certified mail, she said, and when she didn’t hear anything back, she flew to Oklahoma City and went to the treasurer’s office and filled out the forms there in mid-June.

“I’m scrambling around trying to figure all this stuff out,” she said.

More than two months after making her first inquiry, she said the State Treasurer’s Office told her the amount owed to her father, but it wasn’t anywhere near the $40,000 figure for the sale of his land. Instead, the $269.25 held by the state came from utility deposits he had made in Oklahoma City decades earlier.

“I’m thinking it’s the check for the land, that my dad’s going to get paid for the 40 acres. And this check comes in the mail for $269.25, and the land was sold for $40,000 at the auction,” Jill Momaday said.

Making further inquiry, she discovered in September that her dad’s land was a Kiowa County issue and that she needed to contact the county treasurer’s office. She asked a friend who lives on property close to Rainy Mountain, Brenda Hawkins, to meet with Miller, the county treasurer. Hawkins agreed, and she took along Jacob Tsotigh, vice chairman of the Kiowa Tribe.

The meeting went poorly. Miller told them about the unpaid taxes on the property since 2018, her attempts to notify N. Scott Momaday, and the public auction. And because it was now more than a year since the land sale, proceeds were in a county fund and could not be released to the Momaday family.

“It’s very devious, the process that they say they went through,” Tsotigh said. “It was very superficial in terms of them trying to contact Dr. Momaday. I think it was purposeful in order for them to have access to this property.

“It smacks of favoritism and good ol’ boy politics.”

Tsotigh’s perception might seem obvious from an official in a sovereign tribal nation whose ancestors’ nomadic existence across the Great Plains was fundamentally disrupted by white settlement. The United States government attempted to eliminate bison and deny tribes like the Kiowa a resource key to their survival. Wars and treaties shrank their territory, and boarding schools tried to cancel Indigenous cultures altogether. In 1900, Congress even disestablished the reservation that had been promised to the Kiowa and other tribes in the area.

While perceptions may differ, the loss of N. Scott Momaday’s allotment through government machinations and a “public notice” process involving a trio of small newspapers looks to some like one more way to strip Indians of their land.

“It is very coincidental that one individual was able to make a clear profit without much effort,” Tsotigh said. “For them to say they tried to contact him, I don’t think they went through any type of extreme nature to do that. They certainly could have Googled ‘Scott Momaday’ and found out where he was.

“I just wish there was some way that we could compromise and come to some type of resolution that would allow [the Momaday family] to receive some benefit.”

Hawkins, a former public school teacher who grew up near Gotebo, said she also left disappointed after the meeting with Miller.

“Native Americans just get shot down so much,” she said.

Hawkins said Miller or her staff should have contacted Randy Holsted, who leased Momaday’s land for two decades.

“Randy is the only person that’s ever rented N. Scott’s land,” Hawkins said. “He knew he wasn’t dead. He knew his address. He knew his phone number. He knew all of that.”

The chain of events made Hawkins more determined to honor Momaday in Kiowa County.

She decided the building that housed the Boake Store and Trading Post — which her family purchased near Rainy Mountain — would be transformed into the N. Scott Momaday First Americans Education and History Center “to honor, acknowledge and celebrate the life of this extraordinary man.” The grand opening for the privately owned museum is scheduled for Saturday, May 18.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

What about that cell tower?

The fact that Randy Holsted’s son bought N. Scott Momaday’s land led some to look for a motive or possible conspiracy.

Contacted Jan. 4, Randy Holsted said he leased the Momaday property “for quite a while.”

“Me and my family have farmed it for a long time,” he said.

He said his son, Shakota, is farming the Momaday property now.

“My son bought that fair and square at a sheriff’s sale,” he said. “The cell tower was there before the sale.”

Holsted said questions about the cell phone tower were just rumor and innuendo.

“The cell tower is on a different piece of property,” he said. “The property it is on, I own it and have owned it for a number of years.”

Holsted said people may be confused about the property lines because land in the area just east of Mountain View was part of the Momaday allotment. Holsted’s property, however, is a 27-acre tract that had been owned by Lester Momaday, Holsted said. At 27 acres, the tract’s unusual size stemmed from a decision in the 1930s where the town of Mountain View bought some of Lester Momaday’s land to put in sewer lagoons. Lester Momaday’s land was sold in the 1970s, and Randy Holsted said he bought the 27-acre tract about 10 years ago.

Asked when the cell tower was erected, Holsted became frustrated.

“It’s none of your business about when that cell tower was put up because I own the land, I have a deed on it, and the cell tower — it don’t matter if it was put up yesterday,” he said. “It doesn’t pertain to that 40 (acres) that was sold at the sheriff’s sale.”

Kimberly Calcasola, senior vice president and general counsel of Harmoni Towers, said in an email Feb. 15 that the cell tower was built in March or April 2022 — two or three months before the public auction of Scott Momaday’s land.

Records she provided confirmed the tower is not built on Scott Momaday’s former land. It is nearby, but the tower is located on the northwest quarter of the northeast quarter of Section 12, Township 7 North, Range 15 West in Kiowa County. Scott Momaday’s former property is in the northeast quarter of the northeast quarter of Section 12, Township 7 North, Range 15 West.

‘The county really doesn’t deserve that windfall’

Kiowa County District 1 County Commissioner Reeder Reese, whose district covers the property formerly owned by Scott Momaday, said he was taken aback by those who think something nefarious was involved in the sale of the property.

“Not one person would want to take that land away from that man,” he said. “There was no plot, yet that’s what they’re insinuating — that the whole county was in a plot to take away this 40 acres from this guy.”

Miller said the treasurer’s office could not give the Momaday family net proceeds from the sale of his property after the one-year deadline had passed.

“There was nothing we could do to give him his money back,” said. “That would be in violation of my oath to Kiowa County.”

Doing so after the one-year period expired also would set a bad precedent, she said.

“Everything has a guideline. My hands were tied,” Miller said. “Sure, I wish he would have got that money, but it wasn’t going to happen the way the law allowed. And we can’t treat him differently than we would anybody else.”

Frustrated over the situation, Jill Momaday contacted Robert Henry, former judge on the U.S. Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. Before that he served as Oklahoma’s attorney general, a member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives and as dean of the Oklahoma City University School of Law. Later, he served as president and CEO of OCU. His cousin, former Gov. Brad Henry, named Scott Momaday Oklahoma’s Centennial Poet Laureate in 2007.

Robert Henry said he was baffled how Kiowa County officials couldn’t track down Scott Momaday or his family.

“The real shame is that there wasn’t an intense effort to find Scott Momaday,” Henry said. “Given the equity of this situation, it just seems to me that the county commissioners ought to be able to release those funds. I mean, that would make it a little bit better. The county really doesn’t deserve that windfall given what happened here.”

Since her father’s death, Jill Momaday said she tries not to think about what happened to his land in Kiowa County. Months later, she is still working out details for memorial services, possibly in both New Mexico and Oklahoma.

“Circumstances were such at the end there that he didn’t see the notices or wasn’t aware of them,” she said. “For the little pittance of money, we could have paid and kept it. It’s so sad.”

If not for the COVID pandemic, things might have turned out differently, she believes.

“I do place blame on that and wonder how, during these incredible things that happen in life like the black plague or whatever, do we as human beings take anything of that into account sometimes and just try to be more human?” she asked. “Are we human enough to have a little bit of grace sometimes in certain circumstances when you look at the whole picture? Wouldn’t it be great if that’s who we are and we have just a bit of grace?”