Oklahoma has become the 13th state to report a positive case of bird flu in dairy cattle, a developing situation that has featured the U.S. Department of Agriculture making dairy farms eligible for a federal grant program and state agriculture agencies emphasizing biosecurity and new mandates around the testing and transportation of lactating cattle.

Since 2022, the USDA has been monitoring and helping the agriculture industry respond to avian influenza, also known as H5N1. The virus has lingered for the past two years, causing many poultry barn depopulations and occasional spikes in egg, chicken and turkey prices.

But in March, the bird flu was confirmed to have jumped from poultry to dairy cattle, causing some concern about broader economic impacts and potential transmission to humans through unpasteurized or raw milk.

In Oklahoma, the USDA notified the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry on July 11 that a milk sample collected in April from a local dairy herd tested positive for H5N1.

The following day, ODAFF public information officer Lee Benson announced the positive test in a press release. In a phone interview July 17, Benson said an Oklahoma dairy farmer suspected some of their cattle had the virus in April and took a sample. He said that, for unknown reasons, the farmer kept the sample frozen until hearing about a newly expanded USDA program providing assistance to dairy herds whose milk production is impacted by the recent spread of bird flu.

At that point, Benson said, the farmer sent the sample to the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

“When it became apparent that this dairy in Oklahoma may be able to get some aid from the USDA through this new program, this dairy then sent that sample from April to the USDA, and USDA received the sample the first week of July,” Benson said. “They tested it and then found out, and then told us here at ODAFF in Oklahoma last week that it did come back as a confirmed positive case of HPAI.”

The Oklahoma sample first went to a testing facility at Iowa State University and then to the National Veterinary Service Laboratory, which is part of the USDA’s AHPIS network, according to Benson.

The July 12 press release said “the dairy herd has fully recovered, and the farm has not reported any other cases of HPAI.”

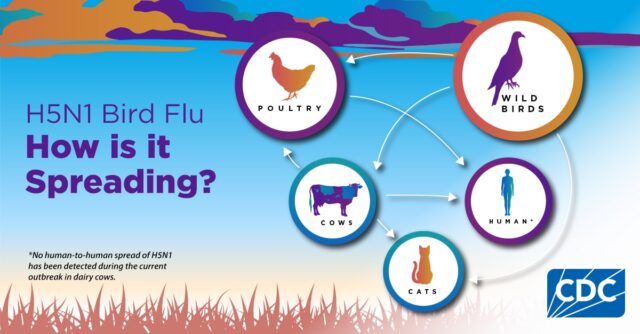

Reports published by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention say bird flu was first detected widespread in wild birds in 2021 and has since affected poultry, dairy cattle and occasionally humans in the U.S.

According to the CDC website, there have been 11 reported human cases of bird flu since 2022, five of which have been confirmed as the H5N1 strain of bird flu. Four were contracted by infected dairy cattle. A Texas dairy farmer who was exposed to infected cattle became most recent human infectee in March. They have since recovered.

Sen. Casey Murdock (R-Felt) runs a cow-calf operation in the Oklahoma panhandle and said the latest bird flu situation is “being blown out of proportion” for the cattle industry.

“It’s very hard to transmit it to humans,” Murdock said. “For the cattle industry, livestock will feel sick for a little bit and then they’re over it. It’s not as detrimental to the livestock industry as it would be for birds.”

While Benson said no humans have tested positive for bird flu in Oklahoma, the Oklahoma state veterinarian has said ODAFF and the USDA continue to monitor the state for cases of Human Pathological Avian Influenza.

“We have been monitoring detections of HPAI in other states since the first detection in March,” Dr. Rod Hall said in Benson’s July 12 press release. “Our team has been in constant communication with Oklahoma dairies asking them to heighten their biosecurity practices.”

Because bird flu has been detected in only a single Oklahoma dairy herd, Benson said state regulators are not currently concerned about its impact on humans, as the disease mainly affects animals and has proven to have little risk to people.

“This is a disease in animals that is no risk to humans right now,” Benson said. “When it comes to consuming pasteurized milk, pasteurized dairy products — that’s safe. Fortunately, this disease in dairy cattle is very mild, and it’s not weeding and not causing death to the cattle or any risk to humans as well.”

Benson said symptoms shown in human cases around the country have been mild and that people have been recovering “just fine.” He said Oklahoma cattle herds have not seen cattle deaths and that there has been little to no decrease in milk production or supply loss to the agency’s knowledge.

“Fortunately, this is a disease that’s very mild to dairy cattle,” Benson said. “What we’ve been seeing based on several other states that had already had it, typically it’s about two weeks of drop in milk production with the cattle, some symptoms. About 10 precent of the herd become infected. It’s not the whole herd, and fortunately what we see typically is that the cows are able to recover (and) get back to milk production.”

Nonetheless, Murdock said his biggest bird flu concern involves potential economic effects from being overly cautious in a low-risk situation.

“They are already taking precautions, and when the CDC is out there saying this stuff, it affects the markets on the Board of Trade,” Murdock said. “You’ll see major swings in what prices are, and that’s the concerning thing for me. With them blowing things out of proportion, it will affect the prices of the commodities, which hurts your regular farmers, ranchers and families.”

On Wednesday, an Oklahoma State University representative confirmed that OSU’s Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory began testing milk samples April 1 for bird flu shortly after it was reported to have crossed species into cattle.

“To date, we have tested 74 milk samples for HPAI, yielding all negative results,” OADDL director Jeremiah Saliki said in a statement. “We expect testing volume to increase substantially in the coming months following an order [Tuesday] from the state veterinarian requiring that all lactating cattle going to exhibitions in Oklahoma must be tested and have a negative HPAI test result within seven days of the exhibition.”

The state veterinarian’s order was posted on Facebook and specifies the new, limited testing requirements.

“Owners of lactating dairy cattle who are planning to exhibit their animals to their county or state fair should contact their veterinarian, who must collect a milk sample and submit it to (the) Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory to be tested for HPAI,” the post states.

The order also prohibits sharing equipment such as portable milking machines and feeding, watering and grooming equipment.

ODAFF recommends increasing biosecurity precautions

In order to contract bird flu, a person must have been in contact with infected animals such as wild birds, poultry and cattle, according to the CDC.

The federal agency reports that the risk of person-to-person spread is low and has not been detected or reported in the United States. Farmers and individuals who commonly work with infected animals, contaminated materials or unsanitized surfaces face increased risks.

“From a human health standpoint? Very, very low risk,” Benson said. “Pasteurized milk (and) pasteurized dairy products are safe to consume. And I’d say there’s no reason to do anything different. Whatever you normally eat, whatever you normally buy from the grocery store — no need to change up your daily habits at all at this time.”

According to a CDC situation summary of the current bird flu issue, “human infections with bird flu viruses can happen when virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose or mouth, or is inhaled.”

“This can happen when virus is in the air (in droplets or possibly dust) and a person breathes it in, or possibly when a person touches something that has virus on it and then touches their mouth, eyes or nose,” the agency states.

The World Health Organization released an April 9 disease outbreak update explaining there have been a few cases of humans infected with avian influenza that are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms such as eye redness and upper respiratory issues. Contracting the virus has also been reported to cause other diseases, including conjunctivitis, gastrointestinal symptoms, encephalitis and encephalopathy, according to the WHO.

Benson said Oklahoma’s state veterinarian and his staff have spoken to dairy producers across the state to encourage enhanced biosecurity and provide resources to combat the spread of the virus.

In response to the confirmed positive bird flu samples, ODAFF has updated a document detailing the state’s biosecurity recommendations, which are broken into five categories: cattle, people, equipment, movements and environment.

Suggestions include preventative measures such close communication between dairy farms and their veterinarians, monitoring dairy herds, keeping cattle separate from other animals, educating employees on biosecurity and sanitation practices, wearing clean clothing and footwear, disinfecting equipment and trailer interiors, and limiting movements to only essential workers.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

USDA announces new programs and new mandates

Before bird flu had reached Oklahoma dairy cattle, the USDA announced an April 29 federal order “to assist with developing a baseline of critical information and limiting the spread of H5N1 in dairy cattle.”

The federal order required mandatory testing for interstate movement of dairy cattle and mandatory reporting.

Before the transportation of lactating cattle across state lines, the cattle must receive a negative influenza A virus test result and must adhere to conditions specified by USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. For any cattle testing positive, the owners must provide epidemiological information, including animal movement tracing.

The mandatory reporting requirement focuses on laboratories and veterinarians, who now must report positive influenza A nucleic acid detection and positive influenza A serology diagnostic results in livestock to APHIS.

In a June 27 press release, the USDA announced it will also begin accepting applications for an expanded emergency livestock assistance program to help dairy producers offset milk lose due to H5N1.

“USDA remains committed to working with producers, state veterinarians, animal health professionals, and our federal partners as we continue to detect the presence of H5N1 in dairy herds and take additional measures to contain the spread of the disease,” said Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack.

The updated program expands the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honeybees, and Farm-raised Fish Program, also called “ELAP.” The announcement of the program expansion apparently triggered the positive milk sample submission from the Oklahoma dairy farmer.

“ELAP assistance is provided for losses not covered by other disaster assistance programs authorized by the 2014 Farm Bill and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, such as losses not covered by the Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP) and the Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP),” according to the USDA FSA website.

USDA began accepting dairy farm applications July 1, allowing those who are eligible to apply for assistance.

To be eligible for milk production loss assistance, adult dairy cattle must be:

- Part of a herd that has a confirmed positive H5N1 test from NVSL;

- Initially removed from commercial milk production at some point during the 14-day time period before the sample collection date for the positive H5N1 test date through 120 days after the sample collection date for the positive H5N1 test;

- Milk-producing, currently lactating; and

- Maintained for commercial milk production, in which the producer has a financial risk, on the beginning date of the eligible loss condition.