Although educators and parents have been working for years to help students recover from drops in test scores as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns — commonly known as pandemic “learning loss” — another emerging effect is straining an already beleaguered educational system as students begin the new school year.

Students born just before the pandemic’s lockdowns of 2020 are beginning to enter elementary school and could display sharp differences from older students who had different experiences during their toddler years, which are crucial to development of a child’s brain.

“It’s not necessarily academic loss, it’s the developmental (loss) to the milestones around social interactions,” AJ Griffin, executive director of the Potts Family Foundation, said in a Sept. 3 interview. “Those are going to be delayed because children learn from other children and from interacting with their peers — even at a very young age. Everything from their childcare center to the church nursery, those were opportunities for social interactions that didn’t occur.”

While developmental gaps among young children with varying experiences are not new, Griffin said the pandemic exacerbated the issue along socioeconomic lines.

“We’re going to see it be worse in the most under-resourced areas in the state,” Griffin said. “So, where kids are already struggling, they’re going to be struggling more.”

Pandemic effects on elementary schools being studied

Nationwide, journalists and academics have already begun to document how kids entering elementary school are exhibiting higher rates of anxiety or depression than their pre-pandemic peers. Some parents and teachers told the New York Times in July that their children have struggled to play with other students and that some kids have been unfamiliar with shapes or how to hold a pencil. The Los Angeles Times reported last year that the pandemic may have even caused an increase in kids who start school without being fully potty trained.

There has been little public discussion of this issue in Oklahoma, but Peggs Public School Superintendent John Cox said Sept. 4 that his kindergarten teachers are on the lookout for such students and have noticed certain changes.

“I think there’s more of a dependence on having an adult right there to help,” Cox said. “We kind of think that is because when COVID hit, parents were forced to be at home and have an iPad or some type of technology there for the child to work on, and parents were forced to help them with it.”

Cox said he felt allowing — and sometimes teaching — kids in his rural eastern Oklahoma district to play with each other would be important in helping them recover from the pandemic and grow as children.

“I think that social isolation really made a difference, especially when you have children playing with each other,” Cox said.

Oklahoma House Appropriations and Budget Subcommittee on Education Vice Chairman Dick Lowe (R-Amber) echoed Cox’s assessment.

Lowe, a former educator, also said he thinks communities will need to do their best to support teachers as they ride the latest wave of pandemic effects.

“We can’t say there’s a new baseline, because the society we live in has the same baseline. We don’t get to back up, we’ve got to make up. Our teachers — that’s a [tough] job to try to make that up. My heart goes out to them,” Lowe said. “This is a new challenge that we’ve never faced, and to be honest, there’s not anything up here that says, ‘Here’s how you deal with it.’ I think a lot of it is going to be figured out in those classrooms by our great teachers we have in the state of Oklahoma. (…) We’ve got to provide whatever they need to be able to do that.”

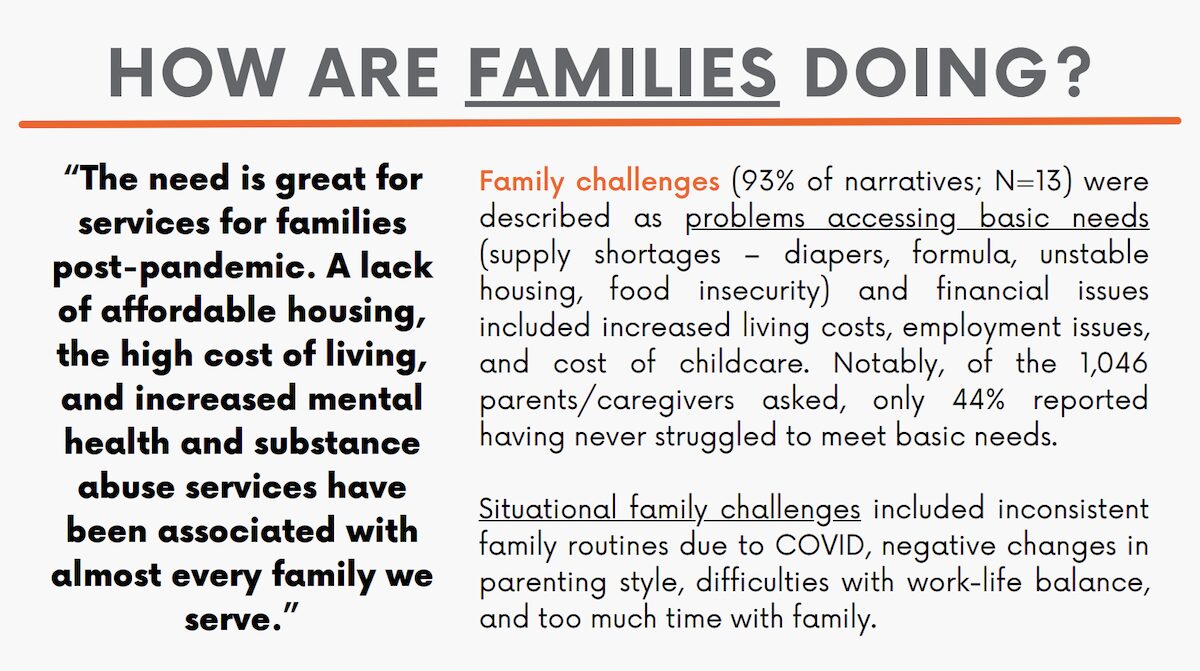

As a first step to finding solutions to these problems, the Potts Family Foundation recently commissioned a report with the OSU Center for Family Resilience that offers the first real data on how the pandemic affected Oklahoma children. Funded with federal American Rescue Plan Act dollars, the report examines challenges facing kids born between 2019 and May 2023, along with their families and care providers.

According to the report, many of those interacting with young children have multiple concerns about how best to support them as they grow.

“COVID kids are just different! I see it in my work in the medical field and with my friends and family,” said one person quoted anonymously in the report. “These kids just act different and interact differently than other kids that I’ve been around.”

Communications directors with Oklahoma City Public Schools and Edmond Public Schools did not return an email and phone call, respectively, seeking comment on this issue prior to publication of this story.

Legislator: Teachers doing ‘their dead-level best’ to help students

Although not unique to Oklahoma or this particular post-pandemic situation, many stakeholders hold a common opinion on how schools and other institutions can best support struggling students: hire and retain more staff.

Oklahoma Public School Resource Center executive director April Grace said many schools across the state need more training for their teachers and more special education teachers.

“Teachers are coming into the profession from so many different on-ramps right now and a variety of experiences,” Grace said. “One of the things we get a lot of requests for are training and support around classroom management.”

The Potts Family Foundation report echoed a similar idea.

“Industry, including childcare, continues to struggle with hiring and retaining staff as wages are low and hours are long with little to no acknowledgement of the tremendous work early childcare providers give to our children day in and day out,” another anonymous person was quoted as saying in the report.

Grace, the former superintendent of Shawnee Public Schools, said she felt the pandemic coincided with other, deeper issues in education, such as the teacher shortage, to create greater challenges for many schools, particularly those in economically disadvantaged areas.

“Not everyone has the resources to have a behavior intervention specialist,” Grace said. “So [districts are] trying to find out, ‘How do we write a successful plan to help retrain or curb this child’s behavior so that learning can happen?’ And we know that that can also create distractions in a classroom.”

But as federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding expires, some school districts, such as Oklahoma City Public Schools, are beginning the 2024-2025 academic year with larger class sizes and fewer educators on staff than they had the year before.

“That’s a hard one, because when we start getting back out of that ESSER, that changes things up without a question,” Lowe said. “Keeping teachers in the classroom is a hard deal. It’s nothing unique to Oklahoma.”

The PFF report also noted that many families are struggling as pandemic-era programs end at a time when inflation has raised the basic costs of living.

“Parents/caregivers and providers indicated the vast majority of families are unable to meet basic needs all of the time,” the researchers wrote. “This is especially true for families who benefited from additional family supports (e.g., rent assistance, unemployment support, etc.) that were offered during COVID. Discontinuation of these supports and the financial ‘social benefits gap’ leave some families under resourced and unable to meet basic needs.”

The first regular session of the 60th Legislature will convene in February. Earlier this year, the second regular session of the 59th Legislature adjourned with little action taken on such topics, despite a number of bills sitting in limbo that sought to address the childcare shortage. State common education funding, however, increased by $25 million one year after it increased by $625 million.

Lowe, who could be in line to become the new chairman of the House’s education appropriation subcommittee, said any tools in existence to help teachers deal with the pandemic’s toll should be made available to Oklahoma teachers.

“I don’t want to ever downgrade what our teachers are doing. They’re working hard. They’re trying hard. They’re discouraged at times,” Lowe said. “Shoot, I was a teacher. I can tell you there’s days I was discouraged, too. But they’re the people that will make a difference in lives, and we’re going to support those people. We’re going to give them the tools they need.”

Lowe said he had spoken to many teachers in his rural district southwest of the Oklahoma City metro.

“They’re excited to get [these kids] in the classroom and do their dead-level best to get them back to where we need to be,” Lowe said. “I have to look at that and think, ‘Thank you, teachers, but also know, with that, we’re getting ready to ask you to do more. (…) We appreciate what you’re doing, but we know what’s coming at you.'”