OKMULGEE — A new lawsuit stemming from a pending lawsuit has slowed proceedings to a crawl before the Muscogee Nation Supreme Court.

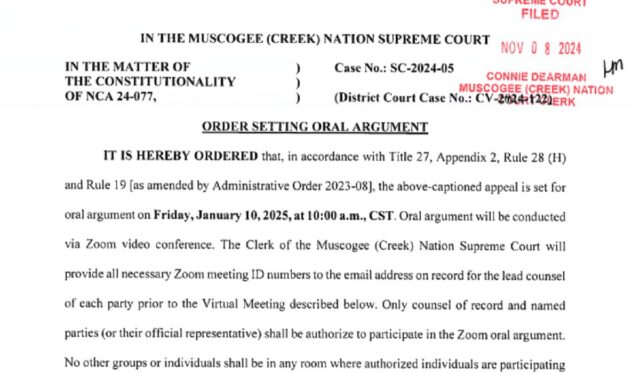

The court has scheduled oral arguments Friday, Jan. 10, in a case questioning the constitutionality of a controversial bill that would allow the nation’s principal chief — with approval from the Muscogee National Council — to appoint temporary “special justices” to the court for cases where a regularly-appointed justice recuses. Arguments are set to be presented virtually over Zoom at 10 a.m. with no observers allowed on the call, but the proceedings are to be live-streamed on the court’s Facebook page. Notably, the order only requires the recording of the livestream to remain available “until close of business” that day.

Court filings indicate the case has raised the temperature on simmering tensions between the tribe’s courts and its other two branches of government.

After Muscogee Nation District Court Judge Denette Mouser ruled that the nation’s 1866 treaty with the United States required the tribe to allow the descendants of individuals listed on the Muscogee Freedmen rolls to be granted Muscogee citizenship, the nation appealed to the Muscogee Supreme Court. When Justices Leah Harjo-Ware and Amos McNac both recused from the case, Principal Chief David Hill introduced NCA 24-077 to the nation’s legislature to allow the appointment of temporary special justices when a justice recuses. The Muscogee National Council passed the bill and approved the appointment of two special justices, James Jennings and Samuel Deere, to hear the Freedmen case. Neither Jennings nor Deere is an attorney, although having non-attorney elders with knowledge of tribal customs serve on courts can be common.

The special justice law contains the same appointment requirements that apply for full Muscogee Supreme Court justices in the Muscogee Nation’s Constitution, which attorneys for Hill and the National Council have argued makes the law constitutionally sound. While the appointment process for special justices is the same as normal Supreme Court justices, those justices are appointed for six-year terms while special justices are appointed for one particular case.

The U.S. Supreme Court lacks a procedure to appoint temporary justices, but Oklahoma law allows the chief justice of the Oklahoma Supreme Court to appoint a temporary justice to hear a case if a justice recuses.

Styled as In the Matter of the Constitutionality of NCA 24-077, the controversial case was initially filed on behalf of Muscogee Freedmen, but court filings appear to indicate the case has evolved into an intergovernmental dispute over the separation of powers within the Muscogee Nation.

Other cases before the Muscogee Supreme Court are also on hold until the special justice law is reviewed.

Tensions rising between MN judiciary and other branches over special justice law

Much like the U.S. federal government and Oklahoma, the Muscogee Nation is made up of the classic three branches of government — the executive, the legislative and the judiciary — originating from a French baron‘s Enlightenment-era writings. By design, the three branches are sometimes in conflict to prevent any branch from becoming too powerful.

Made by attorneys Damario Solomon-Simmons, M. David Riggs and Jana L. Knott on behalf of Muscogee Freedmen, the initial filing of the special justices lawsuit attempted to frame the case as infringement on the judiciary’s independence by the tribe’s legislative and executive branches.

“In calling an emergency session to pass the special justice laws, the Muscogee Nation’s National Council and principal chief violated the separation of powers that protects all the nation’s citizens and those subject to the MCN’s jurisdiction,” the attorneys wrote. “Separation of powers is a critical protector of everyone subject to MCN jurisdiction.”

The fact the Muscogee Nation Supreme Court took up the case indicates at least some of the justices thought the law, combined with its public criticisms, warranted the court issuing an opinion. Portions of the Supreme Court’s orders cited by Hill’s attorney, which do not appear to be fully available online, indicate the court agrees with the separation of powers framing. One order barred the nation’s attorney general from participating in the case, requiring the executive and legislative branches to use their own attorneys.

“This action concerns a separation of powers issue between the nation’s three branches of government. By granting the executive branch’s motion to intervene, all three branches of government are now adequately represented in this action,” the Supreme Court order reads. “The executive branch, through its attorney general, should not be authorized to express a view on behalf of the Muscogee Nation when the issues implicated concern internal disputes between the nation’s three branches of government.”

Another portion of an order notes temporary appointments were possible before the new special justice law, but they required the approval of the principal chief, the speaker of the National Council and the chief justice of the Supreme Court. The court’s current chief justice is Andrew Adams III, while the current speaker is Randall Hicks.

Rod W. Wiemer and O. Joseph Williams — the attorneys representing Hill — explicitly objected to framing the case as a separation of powers issue and accused the Supreme Court’s orders of improperly adopting that framing.

“This case is a declaratory judgement action challenging the constitutionality of a Muscogee Nation law brought by private litigants who allege they are affected by the law. It is improper for the Supreme Court to inject itself into the shoes of the petitioners in this case,” Wiemer and Williams wrote. “The canon of constitutional avoidance requires this court to avoid separation of powers issues when they are unnecessary, rather than to inject itself as a party into litigation to raise such issues.”

The principal chief’s attorneys also objected to the court’s reference to a prior law requiring the chief justice to approve temporary judicial appointments.

“This court cannot complain that ‘the judicial branch has been effectively removed from its role in making temporary appointments to the Supreme Court’ when that role was granted by the National Council and principal chief through legislation,” Hill’s attorneys wrote. “What was granted by legislation can be removed by legislation. Only the National Council and principal chief have constitutional appointment powers.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

With recusals common, Council claims historic problem needed solution

Recusals and decisions by a less than full bench have been a common occurrence in the Muscogee Nation Supreme Court, with 72 percent of its decisions between 1985 and 2010 issued by fewer than six justices, according to Ellis v. Checotah Muscogee Creek Indian Community. Judges are supposed to recuse from a case when they have a direct conflict of interest or if there is an appearance of impropriety were they to participate.

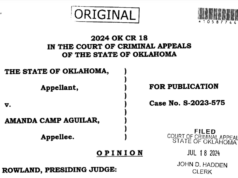

Muscogee law contains both the “four-in-agreement” rule — requiring four justices to agree at the conclusion of the case — and the quorum rule, which requires that at least four justices participate in hearing every case. Resolved in 2013, the Ellis case held that the only constitutional reading of the two requirements was that the “four-in-agreement” rule “includes an inherent presumption of six qualified, participating justices,” implying cases with fewer participating justices do not need four justices in agreement.

While the Ellis decision explicitly stopped short of overturning the four-in-agreement rule as unconstitutional, it limited its application to cases heard by at least six justices.

RELATED

Creek Freedmen allege ‘court packing’ ahead of historic Muscogee Nation hearing by Tristan Loveless

According to a brief submitted by general counsel for the Muscogee National Council Kyle B. Haskins, the new special justice law was passed “out of concern of federal scrutiny over final orders and mandates issued by less than a simple majority of all six members of this honorable court, not only in [the Freedmen case], but also in other critically important cases coming before the court that may proceed to the federal system.”

With the number of criminal prosecutions by the Muscogee Nation substantially increasing after the McGirt v. Oklahoma decision, the National Council’s brief argued that the question of whether an unhappy defendant will seek federal review of his or her case is more a question of when than if.

Haskins argued the council based the new special justice legislation on the Ellis decision and was attempting to provide a mechanism for the four-in-agreement rule to apply ubiquitously while allowing the court to function given the reality of frequent recusals. Attorneys for Hill, the principal chief, argued that since a 2013 amendment to the Muscogee Constitution, no case has been decided without four justices in agreement.

With the legislation arising from the ambiguities created by the Ellis decision and the Muscogee Supreme Court’s subsequent increase from six justices to seven since, the court’s ruling on the special justices could be one of the most important Muscogee constitutional law decisions of the decade.