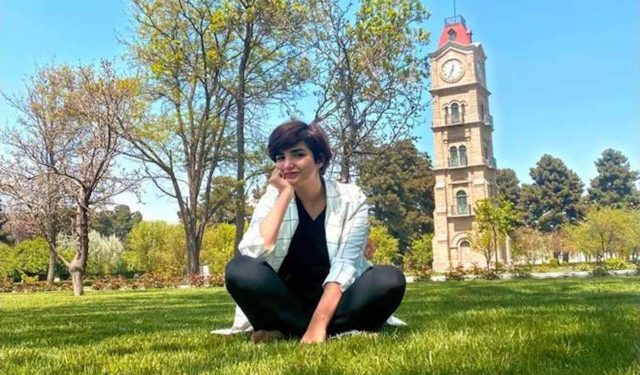

(Editor’s Note: Shabnam Khalilyar, 26, is a University of Oklahoma Gaylord College journalism fellow preparing to enter graduate school this fall to study international diplomacy. She was on one of the last planes out of Afghanistan in 2021 after the country fell to the Taliban. In Afghanistan, she worked as a journalist and, until leaving the country, served as head of public opinion analysis and media monitoring for the office of the presidential chief of staff.)

A year is not a long period for the immeasurable pain and suffering of your country’s loss to be healed. Perhaps decades won’t be enough. For those still stuck in Afghanistan, the bitter story of Aug. 15, 2021, is not over yet.

A generation grew old overnight, burying their hopes and desires beside the graves of their loved ones and martyred soldiers.

Now safe, I continue having flashbacks to the weeks before and after Kabul fell to the Taliban.

After mid-July, the dynamic atmosphere in the presidential palace compound known as the Arg, where I had worked since July 2020 for the chief of staff to the president of Afghanistan, deteriorated dramatically. The compound no longer had the vibrancy of the past. The luxurious cafe, which until a few weeks before, when it was hit by missiles, was the gathering place of stylish young people who worked in the office, was nearly empty.

It was terrifying when outlying provinces rapidly fell to the Taliban, but some people remained confident that Kabul would not topple, at least for a year or two. According to conventional belief, the fall of the provinces was part of a deal with the Taliban, and after a year there would be a transitional government.

For people who truly believed in liberty and civil norms, however, neither situation was optimal. Even in the case of a transitional government, the country would be offered a repressive Islamic regime disguised in the form of a republic, coalition or something else, but which in essence was an Emirate or caliphate.

This story was reported by Gaylord News, a Washington reporting project of the Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Oklahoma.

At the negotiating table, the Taliban were not willing to compromise. They demanded the lion’s share. But the Afghan negotiators, including representatives of President Ashraf Ghani, who had been chosen in a disputed presidential election, didn’t seem very reliable.

Both sides were in Doha to bargain for their share of a future Afghan government, not to defend their values. Nearly all of Afghanistan’s politicians pretended to their Western counterparts to be liberal and democratic, but this was just was a ploy to grasp power.

These were the power-lovers who would not hesitate to transform their subjects from suited, shaven liberals into turban-wearing, bearded Mullahs. A number of previous officials who returned to Kabul and swore allegiance to the Taliban made this a decisive reality.

The fateful night that turned our world upside down

Toward the last week of July, the headlines became truly alarming.

The mass killing of civilians in Malestan, a town in the southeastern province of Ghazni, and in the southern province of Kandahar added to the fear.

On July 24 alone, the headlines of the local newspaper spoke of an average of 325 killings a day between May 1 and July 15; the deployment of 20,000 Tajik forces to the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border; the dramatic fall of provinces to the Taliban; and the murder by the Taliban of Khasha Zwan, a comedian in Kandahar.

In spite of all the insecurities, many officials inside the Arg, some very well-informed, were unprepared for the tragedy. Even many of those who had passports and visas in their pockets had not booked flights. And those who had flights out of the country had booked them for well after Aug. 15, the fateful night that turned our world upside down.

On the morning of Aug. 14, residents were stunned by the local headlines. The Taliban had captured eight major cities with no comment from security officials. That afternoon, not many staff members were around in the presidential palace dining hall.

“I am afraid that on a very normal day, just like today, we may hear about Ghani’s escape from the country through news headlines,” I said to my colleague while having lunch. “They may carelessly surrender us — who cares about us?”

She replied, “There is no doubt, they are really mean toward us.”

I never thought that day would be tomorrow.

During the afternoon, office staffers were waiting for Ghani’s televised speech. Some expected him to resign and declare a transitional government. Contrary to those expectations, he did not resign, and he spoke only vaguely about the situation.

At 9 a.m. on Aug. 15, the presidential palace was utterly spiritless. Few people showed up for work. The empty courtyard of the Arg was a sign of the sinister fate that awaited. The president’s protective service members, who were usually numerous and vigilant, were not present at the last security check gate. Shortly after I arrived, someone directed us to “go to your home, the Taliban have attacked Kabul.”

Those of us who had shown up for work were in shock. We realized we were all wanted by the Taliban because we worked for the president’s office. We grabbed our belongings and scurried out of the compound. Everything had changed in the blink of an eye.

The streets were jammed in the Shahr-e-Naw neighborhood, where most foreign offices and hotels were located, and in the Wazir Akbar Khan, the city’s wealthiest neighborhood.

Crowds of people who had fled their workplaces were desperately seeking shelter. Even hospitalized patients were being taken to their homes. Those too infirm to walk were carried on the shoulders of loved ones. Anxiety pulled on the faces of everyone in the street.

By evening, Kabul and some remaining provinces were handed to the Taliban without a single bullet fired. The prisons were emptied of thieves, thugs, ISIS members and Taliban detainees. The jails began to fill with former security forces, journalists, civil society activists and whoever opposed the Taliban. Hundreds and thousands of innocents were detained, tortured and killed in those dim and damp cells.

An alien Kabul

On Aug. 17, I encountered a city that seemed to have landed from a science fiction movie — an alien Kabul, a masculine Kabul. The city lacked women, lacked joy and lacked life.

The message to the enlightened generation of Kabul was clear: this city belongs to you no more. A great number of people preferred not to see a dead Kabul and escaped the country. I was one of them.

On Aug. 30, desperate after days of trying to get into the Kabul airport, I fled the city in which I had been raised for Mazar-e-Sharif, a city in northern Afghanistan from which a few flights were still departing.

The last hugs and leave-takings, with no idea when or if I would see my loved ones again, were brutal. I gave my grandpa, who had raised me with love and passion, a tight hug.

The most important thing to him was my safety, and with no hesitation he let me go. But, later, on the day in October when he knew I was flying to the United States, and we realized we might not see each other again, we cried during the video call.

It is impossible to pack all of your life into a backpack, but the good memories traveled with us, in our hearts and minds. The memories are helping us to survive this period, away from our loved ones, in exile.