(Editor’s note: This article is part of “America After Roe,” an examination of the impact of the reversal of Roe v. Wade on health care, culture, policy and people, produced by Carnegie-Knight News21. For more stories, visit americaafterroe.news21.com. News21 reporters Joseph Kual Zakaria, April Pierdant, Peyton Brooks and Jada Respress contributed to this report.)

By Elise Catrion Gregg | News21

AUSTIN, Texas — Amanda and Josh Zurawski sit in the house they bought last year, the dream home they intended to share with their future daughter.

They’ve told their story too many times now, but they brace themselves to tell it once more — from a room just above the backyard where they will one day plant a tree in memory of the baby who never made it home.

It will be a willow, in honor of the name they chose for their little girl.

The Zurawskis went through about 18 months of exhausting fertility treatments before learning that Amanda was pregnant in spring 2022. But that August, when she was about 18 weeks along, something went terribly wrong.

(Video by Joseph Kual Zakaria/News21)

At the hospital, Amanda was diagnosed with cervical incompetence, meaning there was virtually no chance her baby would survive past an inevitable premature birth. Normally, doctors would perform an abortion to end the pregnancy to prevent the mother from developing an infection.

But the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson decision had overturned the precedent of Roe v. Wade one month earlier, and the Zurawskis live in Texas — where abortion is banned at six weeks and a second trigger law was just days away from taking effect, allowing abortions only if the mother has a life-threatening condition, risks death or faces “substantial impairment of a major bodily function.”

“Her heart was still beating, and my life wasn’t considered at risk,” Amanda said. “So, until one of those two things changed, they couldn’t do anything.

“We just had to wait.”

She was sent home with instructions to monitor herself for infection. Days later, she developed sepsis. Her baby, Willow, was delivered — and died. Now Amanda may never be able to have a child.

“It was just despair,” she says, fresh tears in her eyes.

The Zurawskis are tired of sharing this story, tired of reliving this heartbreak. But they do it — for the media, for lawmakers, for judges, for anyone who will listen — because they so desperately want to help others avoid going through what they’ve been through.

“People shouldn’t have to die,” she said, “for lawmakers to change some of these restrictions.”

‘How sick is sick enough?’

While the abortion debate often centers on elective procedures, the reality is that out of the hundreds of thousands of abortions performed in the U.S. annually — at least 620,000 in 2020, according to government statistics – many are because of medical emergencies or to end a pregnancy where a baby would not live long, if at all.

Yet in Texas and beyond, pregnant individuals have been unable to get needed care because of state abortion bans that have left doctors unsure of what procedures they can perform without facing civil or even criminal liability.

State policies on abortion vary widely a year after the U.S. Supreme Court ended federal protections. States like New Mexico, Colorado and Oregon have few if any limits, but 20 states have laws on the books banning abortion at 18 weeks of pregnancy or earlier.

Restrictive states have exceptions to preserve the life of the mother, but trying to interpret those has put both doctors and patients in a potentially life-threatening bind.

“How sick is sick enough?” Dr. Nisha Verma, an Atlanta OB-GYN, asked a crowd of doctors at this year’s conference of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which represents over 60,000 members from North and South America.

“How lethal does a fetal anomaly have to be?”

Do abortion bans compromise maternal health?

Already, studies are showing the effects of these laws on maternal health.

In one paper, published in May in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology, researchers interviewed 50 providers across Texas who cared for patients with life-limiting fetal diagnoses or who had health conditions that threatened their pregnancies.

Even before implementation of the state’s six-week ban, “administrative approval processes and referrals for abortion delayed care and endangered patients’ health,” the study found, but the ban worsened things.

“You really can barely imagine what it’s like for a woman or a couple to be faced with a devastating diagnosis for the fetus … and then they’re told by the doctor, ‘Well, good luck to you. Jump on Google and see where you can find a place to get your termination,’” one specialist told researchers. “It’s just horrifying.”

At the University of California San Francisco, researchers are in the midst of another study examining the impact of abortion bans on clinical care. Early results published in May found these laws had contributed to delays in treatment, poorer health outcomes and increased costs.

“In several cases, patients experienced preventable complications, such as severe infection or having the placenta grow deep into the uterine wall … because clinicians reported their ‘hands were tied,’ making it impossible for them to provide treatment sooner,” researchers wrote.

The U.S. has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. And even before the reversal of Roe, studies showed these deaths were higher in states with restrictive abortion laws.

For many OB-GYNs, the connection is clear: Abortion bans compromise maternal health.

“We’ve definitely seen a correlation in the data between states that have more abortion restrictions and those that have worse maternal morbidity and mortality – and we’re already seeing this play out,” Verma, the Atlanta obstetrician, said in an interview with News21.

Abortion laws have left many doctors in a state of uncertainty

Some lawmakers say none of this was what they intended.

Texas State Sen. Bryan Hughes, the Republican who sponsored the state’s six-week ban, did not respond to an email or phone messages from News21.

But in an August 2022 letter to the Texas Medical Board, he said he was aware of complaints that hospitals “may be wrongfully prohibiting or seriously delaying” life-saving care to patients with pregnancy complications. He pointed to “confusion or disregard” of state laws allowing for abortion in medical emergencies, and said the issues must be corrected.

Amy O’Donnell, spokeswoman for the anti-abortion Texas Alliance for Life, said that clarification needs to come from the Texas Medical Board – not the Legislature.

“For any physicians who are perhaps … confused on our clear pro-life laws, I would just encourage them to also reach out and see if they can get that clarification,” she said.

In addition to Hughes, News21 sought comment from seven other sponsors of abortion bills in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, Nebraska and Tennessee.

Only Republican Sen. Erin Grall of Florida spoke about the abortion legislation she’s sponsored, including that state’s six-week ban. In emergency situations, Florida requires doctors to certify in writing that an abortion is necessary to save the mother’s life, to avoid substantial injury or because of a fetal anomaly.

The language, Grall said, “gives the utmost respect to the doctor and allows the doctor to make the determination based on their training and education and experience.”

She and others have rejected the idea of developing a specific list of complications that might warrant a termination.

“If you are prescriptive with a list, you can miss things just because of the scope of the human medical condition,” she said. “And so, the way in which our language is drafted, I think, gives that discretion to the physician.”

Whether they include a specific list of exceptions or vague language, abortion laws have left many doctors in a state of uncertainty.

“Medicine is not black and white. There are always gray areas,” said Dr. Leah Tatum, an OB-GYN in private practice in Austin. “I think that highlights why there shouldn’t be a law in the first place to restrict that care.”

Verma said, “There’s not a line in the sand where someone goes from being totally fine to acutely dying.”

‘That’s what I need to save my life’

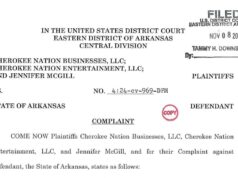

In Texas, 13 women and two doctors have sued the state, arguing its abortion law “has caused and threatens to cause irreparable injury” to patients. Amanda Zurawski is the lead plaintiff.

“It’s about giving a voice to all of the women that this is happening to, that it has happened to, that it will happen to, that don’t feel like they can speak up,” she told News21. “And hopefully, ultimately, it will give courage to other women and men to speak up in their own states.”

The details of each plaintiff’s story are unique, but for the outcome.

One, carrying twins, had to travel out of state to abort her nonviable fetus to save the life of the other.

One flew to Colorado because doctors in Texas wouldn’t perform an abortion after her water broke early and she was told her baby would not survive.

One couple delivered and watched their son slowly die over the course of a few days.

Four of them learned their fetuses had anencephaly, a defect in which a baby is born with an underdeveloped brain and an incomplete skull and dies hours or days later.

Most of them had to spend extensive time, money and energy traveling elsewhere to get abortions. Several had to wait at home, eventually delivering their stillborn babies.

Some, like Amanda Zurawski, suffered complications that now put them at higher risk of experiencing difficulties getting pregnant again – or delivering a healthy child.

“If I had one single message to the general public it would be: Realize that the pregnancies we’re talking about in this lawsuit are all wanted pregnancies – very wanted pregnancies – that then were complicated by a condition … where abortion became the best response to it,” said Dr. Judy Levison, a retired Houston OB-GYN who joined the lawsuit as a plaintiff.

“I’m sure there are many of the women involved in the lawsuit who never thought they would ever — ever — have an abortion (…) and yet when faced with the reality of a medical complication realized, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s what I need to save my life.’”

Levison, a professor at Baylor College of Medicine, retired from her practice last year after Texas’ six-week ban took effect. She remembers the moment she made that decision.

She was talking with a patient, doing what she’d always do — recommending a prenatal blood test that can detect certain fetal abnormalities at 15 to 22 weeks of pregnancy. In some cases, those abnormalities can cause serious medical issues or prevent a baby from living.

With that information, parents can decide whether or not they want to terminate a pregnancy.

As she went to say the word “abortion,” though, Levison stopped short.

“I suddenly realized, wait a minute, what am I doing offering that as an option?” she recalled. “My patients are primarily low income. They can’t afford to take days off from work, find childcare, go out of state, drive or fly somewhere else, and pay for an abortion.”

Levison joined the lawsuit because she knew other physicians might not feel safe doing so.

“I had said to them many times, ‘If there’s ever anything that you feel like you can’t say publicly, because you are younger than I am, you have young children, you have families you want to protect … let me know,’” she said.

“I’m coming toward the end of my career, and if I get fired, or whatever, that’s OK. … I am proud to be a voice for so many of my colleagues who hesitate to speak.”

“We’re a part of this lawsuit in an attempt for the state to help clarify,” Josh Zurawski said. “If someone like Amanda would get pregnant again, and if the same thing would happen, we’d simply ask the state to say you agree that something really terrible shouldn’t have to happen.”

In response to the lawsuit, the state has said in court records that the law is clear and the plaintiffs “cannot show that their alleged injuries” are because of the abortion bans themselves.

“The patients’ alleged injuries were the result of the independent actions of their medical providers who determined that they did not qualify for the medical exception,” one filing reads.

On Aug. 4, a Texas judge issued an injunction blocking the state’s enforcement of abortion bans in emergency situations and saying doctors may use their own judgment to determine when to terminate a pregnancy in an emergency. The Texas Attorney General’s Office appealed that to the state Supreme Court, and the bans remain in place pending the high court’s decision.

‘We’ve never had to think of criminal stuff’

In June, KFF, an independent health policy research group, released the results of a survey of OB-GYNs and their experiences one year after the reversal of Roe.

Nationwide, 44 percent of doctors said the end of federal abortion protections had worsened their decision-making autonomy, and 36 percent said their ability to practice within the standard of care had worsened.

Those numbers climbed among doctors practicing in states with abortion bans – to 60 percent and 55 percent, respectively.

The vast majority of OB-GYNs surveyed also said inequities in maternal health and management of pregnancy-related medical emergencies had worsened in the past year.

Further, 42 percent of doctors reported being more concerned about their own legal risks – a number that rose to 61 percent among doctors working in states with abortion bans.

In short, the landscape for practicing obstetricians has forever changed in America.

“We’ve always had to worry that something bad was going to happen and we were going to get blamed,” said Dr. Nikki Zite, an OB-GYN and a vice chair in the obstetrics and gynecology department at the University of Tennessee School of Medicine. “But we’ve never had to think of criminal stuff.”

Exceptions under Tennessee’s abortion ban only came this past April, allowing abortions to be performed for ectopic and molar pregnancies or to prevent the death of the pregnant woman or serious risk of “substantial and irreversible impairment of a major bodily function.”

“Even ectopic pregnancy or miscarriage management – if there’s a heartbeat, those things are felonies,” Zite said. “Any time there’s vagueness in a law that criminalizes health care, you have various interpretations and you’re going to have health care delays and impact on care.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists is working to help providers navigate this new legal reality and teach them how to advocate to protect access to reproductive health in their home states.

The organization has an online tool kit and conducts training about the importance of preserving the patient-physician relationship and protecting access to evidence-based care.

Abortion was a dominant theme at the group’s May conference in Baltimore, where providers shared stories and advice.

During one session, Dr. Ghazaleh Moayedi, an OB-GYN in Dallas and founder of Pegasus Health Justice Center, encouraged colleagues to be more proactive in shaping appropriate abortion-related policies wherever they may work.

“It is right now that you should be thinking of who in your institution is supportive and how you can leverage that support now to protect people in the future,” Moayedi said. “Who is involved in the policymaking and policy-reviewing is critically important.”

Another provider, Dr. Rachel Flink-Bochacki of Albany, New York, noted there had been some instances in which doctors and hospitals were overcautious in interpreting abortion laws.

“Though hospitals cannot and should not defy the law, we can work to preserve all care that is allowed,” she said. “We don’t need to read things more conservatively than is necessary.”

Many doctors working in states that now have restrictive abortion policies are juggling patient loads with lobbying.

Verma has testified before Congress on several occasions.

“I did not become a doctor to be in politics. I did not become a doctor to be talking to the media every day,” she said in an interview. “But I’m the one sitting down with patients every day, hearing their stories, hearing all of the pain and the suffering that they are having to go through because of these laws.”

Dr. Jonas Swartz, an OB-GYN and professor at Duke University in North Carolina, spent the legislative session writing emails and making calls to urge lawmakers to reject that state’s 12-week ban, which took effect July 1 after the Legislature overrode the veto of the governor, a Democrat.

“I met with legislators to express my concern (…) and try to tell my patients’ stories,” Swartz said. “It feels like those conversations (…) fell on deaf ears.”

‘The thought of being pregnant in Texas again is terrifying’

Joining this fight, in many places, are women like Amanda Zurawski.

She and Josh, who are both 35, are trying again to conceive. But the infection Amanda suffered last year left scarring, and one of her fallopian tubes is now permanently closed.

“We’re really lucky to still have Amanda with us,” her husband said.

The couple know others who have changed their plans to start a family or moved out of Texas because of what Amanda experienced.

“The thought of being pregnant in Texas again is terrifying,” she said. “Who’s to say that the exact same situation wouldn’t happen to me again?”

However, they both work in the tech industry in Austin and, they said, it’s home. So, they’re staying.

“Our lives are here,” Amanda said. “We shouldn’t have to relocate our lives because of terrible laws.”

But there’s another reason she and her husband won’t leave.

“They want us to run away. They want us to not put up a fight,” she said. “Somebody has to stay and fight and make change, or else it’s just going to keep getting worse.”