(Editor’s Note: This is the third and final piece in a series of stories about an ongoing land dispute between the Wichita, Caddo and Delaware nations in western Oklahoma. The first story can be found here, and the second can be read here.)

ANADARKO — Thousands of American Indian children died at residential boarding schools. How many thousands may never be known, and even the location of one school cemetery in Caddo County remains uncertain.

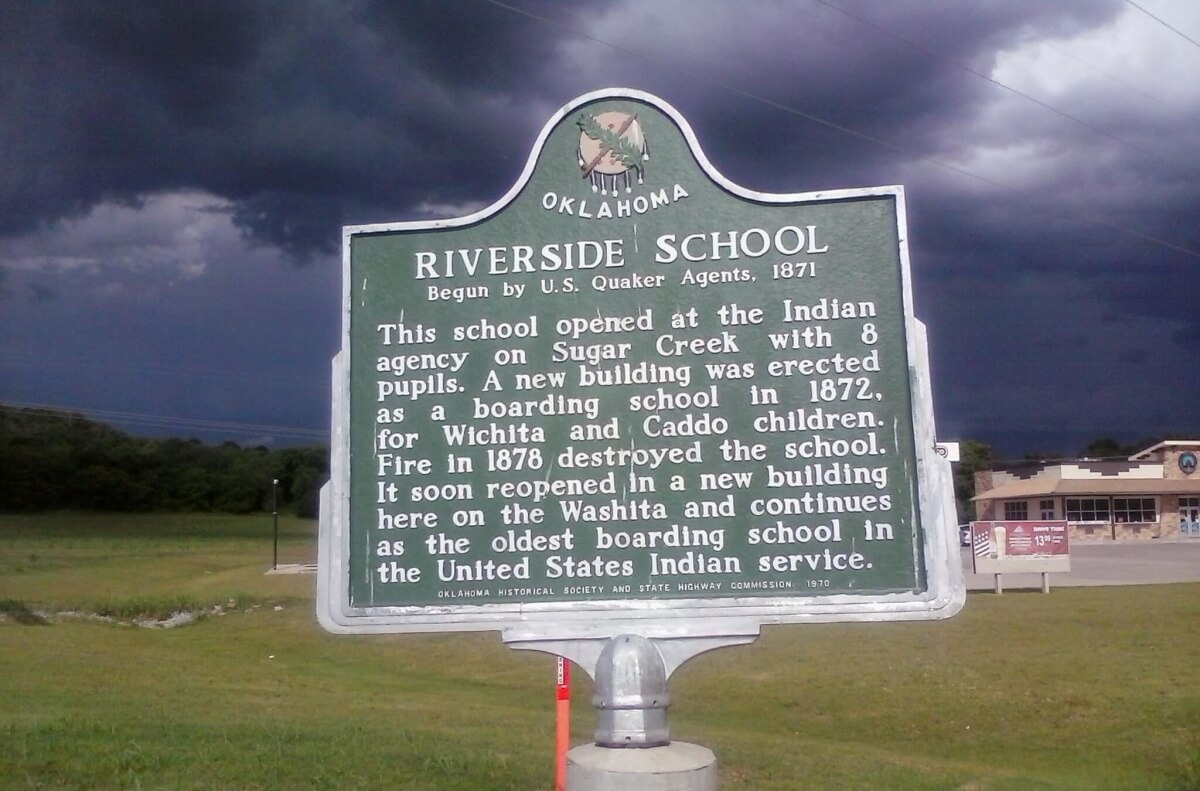

At least one school cemetery and possibly others exist near Riverside Indian School. Owing to a lack of records, no one knows for certain how many children have been buried here since the school opened in 1871, nor do they know exactly where all the graves are located.

“This is a small town. How come we don’t know for sure where the cemetery is?” asked Chelsea White, curator of the Anadarko Heritage Museum and an enrolled Kiowa citizen.

Despite being surrounded every working day by the county’s historical records, White isn’t exactly sure where the cemetery is, either.

“I’ve heard the cemetery is actually behind Riverside,” she said.

After the Civil War, the U.S. government set up many boarding schools for Indians across the country, often near military installations. Sometimes parents sent their children to the boarding schools willingly. Other times, they did not.

“A lot of children were just taken. They did not want to go,” White said.

All of the Indian boarding schools had cemeteries.

“That conveys a message in itself,” said Kerry Holton, president of the Delaware Nation. Holton’s great-great-great grandfather, the Delaware chief Black Beaver, lived near the site where Riverside was built and helped the agents and others who worked there.

Holton said it’s hard to imagine a boarding school today erecting a cemetery next door with the expectation that a percentage of the students who attend will die and be buried there.

Background on the area

Christian missionaries set up the first boarding schools for Native American children. Later, the U.S. government became more heavily involved after President Ulysses S. Grant implemented his “Peace Policy” in 1869. Under the policy, federal efforts shifted from fighting Indians and using the military to contain them in reservations to educating them in schools often designed to separate them from their culture and make them more like white Americans.

RELATED

Caddo, Delaware tribes fighting Wichita development by Stephen A. Martin

Riverside Indian School, not to mention the nearby town of Anadarko, was built near the Wichita Indian Agency. An earlier agency had existed between 1859 and 1862 but closed during the Civil War. The agency was reestablished in 1871 about a mile north of the Washita River. The agency for the Wichita, Caddo and Delaware moved to its present Anadarko town site south of the Washita River in 1878 after it was consolidated with the one for the Kiowa, Comanche and Apache. The school remained at the site to the north.

Books reveal glimpse of life at boarding school

It has been a while since anyone published a book on the Riverside Indian School’s history, although two were written in 1971 for the school’s centennial.

One of them, A History of Riverside Indian School, Anadarko, Oklahoma, 1871-1971, was written by Ruby W. Shannon, who taught English and journalism at the school from 1964 to 1970.

Initial classes were held at the agency in the spring of 1871. In the beginning, it was supposed to be a day school, with students who lived nearby going home each night. Still, most of the students came from at least four or five miles away.

“They often spent the night on campus, sleeping behind a log or fence or anything that could afford a windbreak,” Shannon wrote in her book.

When the school reopened in fall 1871 following a summer break, the agency staff had set up a makeshift dormitory with one room for boys and another for girls. A permanent school facility replaced the makeshift one in 1872 “a short distance” from the agency.

Assimilation over education

Museum curator White’s mother graduated from Riverside Indian School.

“That’s where she had her memories,” White said. “That’s where she had her friends.”

Treatment was harsh at many of the government boarding schools, as the Bureau of Indian Affairs increasingly made assimilation — and not education — its main priority.

“Kill the Indian, save the man,” a slogan attributed to Carlisle Indian School superintendent Richard Henry Pratt, was adopted throughout what was then called the “Indian Service.”

RELATED

Wichita Historical Center progresses despite land battle by Stephen A. Martin

It is estimated that at least 6,000 children died in Canada’s boarding schools for Indian children. Because of poor record keeping, it is nearly impossible to establish the number of children who died in similar schools in the United States.

A federal panel called the Meriam Commission issued a report in 1928 declaring that death rates for Indian children in the U.S. were six and a-half times higher than for students of other ethnicities. The report called for changes in the way the government operated the schools, but many of the changes remained unimplemented until the 1960s.

White said the schools may have started out as an attempt to assimilate Indians, but in time they became places of refuge for some.

“In some ways, it is a bit of — I don’t mean to be too cliché — a blessing,” she said.