By Sean Holstege

News21

SPARTA, Ga. – The cleansing of America’s voter registration rolls occurs every two years and has become a legal battleground between politicians who say the purges are fair and necessary, and voting rights advocates who contend that they discriminate.

Voting rights groups repeatedly have challenged states’ registration purges, including those in Ohio, Georgia, Kansas and Iowa, contending that black, Latino, poor, young and homeless voters have been disproportionately purged. In Florida, Kansas, Iowa and Harris County, Texas, courts have ordered elections officials to restore thousands of voters to the registration rolls or to halt purges they found discriminatory.

The 1993 National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) mandates that state and local elections officers keep voter registration lists accurate by removing the names of people who die, move or fail in successive elections to vote. Voters who’ve been convicted of a felony, ruled mentally incompetent or found to be noncitizens also can be removed. The U.S. Election Assistance Commission reported that 15 million names were scrubbed from the lists nationally in 2014.

Specific geographies exhibit purge bias

News21 analyzed lists of nearly 50 million registered voters from a dozen states and 7 million more who were removed over the last year. By comparing voter registration and purge lists against U.S. Census data, News21 found no national or statewide pattern of discrimination against voters based on race, ethnicity, poverty, age or surname.

But the data did show that purges disproportionately affected minority or low income voters in certain communities and white voters in others. In Cincinnati, poverty rates and voter removals appeared interrelated, while race appeared to affect the removal of voters in rural Hancock County, Georgia. In Vermillion County, Indiana, a shrinking population accounted for large numbers of white registered voters being removed from the rolls.

David Becker, the director of elections initiatives at the nonpartisan Pew Center for Charitable Trusts, said the national pattern makes sense to him. “I think you’re finding exactly what I’ve found in my experience,” he told News21.

But Michael McDonald, a University of Florida political scientist who created the United States Election Project to track election and demographic data, said he was surprised by the lack of a pattern in the national findings, although hidden patterns of discrimination can be found on the local level. “Sometimes you have to look under the hood,” McDonald said.

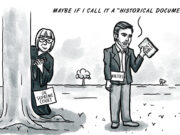

Conservative groups pursue purges

Conservative activist groups view inaccurate registration rolls as a problem for democracy. The conservative American Civil Rights Union has sued eight counties to cleanse the rolls. A year ago the Public Interest Legal Foundation, which litigates on behalf of the ACRU, said it sent warning letters to 141 more. In January, the legal foundation said it threatened to sue 30 counties.

“Across the country, hundreds of other counties have more registered voters than people alive. If they don’t clean up their rolls, they risk litigation,” ACRU chairwoman Susan Carleson wrote on the group’s website. “Every time an illegal voter casts a ballot, it steals someone else’s legal vote. The goal is to ensure the integrity of the voting process.”

The ACRU sued three small counties in Texas along the Rio Grande, which are overwhelmingly Latino, plus four Mississippi counties with black populations ranging from 34 percent to 72 percent. In Mississippi’s Jefferson Davis and Walthall counties, plus Zavala County, Texas, the ACRU won what it called “historic consent decrees” to compel reinvigorated purges.

Sean Young, senior staff attorney for the Voting Rights Project at the liberal-leaning American Civil Liberties Union, said the renewed focus on purging registration lists is no coincidence.

“These groups are trying to use the statutes in the NVRA as a tool to disenfranchise voters,” Young said. “Their efforts have certainly been reinvigorated, in direct response to record numbers of registrations of African-Americans.”

State practices vary widely

Local election officials clean up voting registration lists under state laws governing who should be removed from the lists. Some states bar felons from voting, but they vary dramatically on which crimes disqualify voters or how quickly they can be reinstated. Some, but not all, states require elections officials to mail warning notifications to voters whose names are slated for removal. States also vary on how many elections a voter can sit out before being classified as “inactive” and later culled.

Most states work together or with the federal government to compare voter registration lists to stop people from voting in two states in the same election. One in eight Americans move every year and often remain registered in two places. Few cancel their old registrations. The NVRA directed local elections officials to mail reminders to registered voters who had stopped voting in their jurisdictions to verify whether voters still live where they are registered and to establish who has moved. Those who fail to respond are placed on an inactive list and cut from voter registration rolls after one more missed election.

An attainable goal

In 2005, Kansas created the Interstate Crosscheck System in which 30 states compare registration lists for duplicate entries. When duplicate listings are found, state elections notify each other or local elections offices. It’s up to those local offices to remove those names from the voter rolls. Some do, some don’t.

Pew created another name-matching tool in 2012. Its Electronic Registration Information Center has 21 state partners and compares more extensive records than Crosscheck.

At least 16 states also work with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to apply its immigration database, called the Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements, or SAVE, to confirm the citizenship of registered voters.

Some states use multiple systems to verify registrations. About 24 million U.S. voters have a mismatched name, address, signature or other clerical error on their voter registration forms, according to Pew, that can cause them to be struck from the rolls.

Nationwide, there are around 10,500 state, county and local elections offices. Resources for managing elections vary widely from large urban counties like Chicago’s Cook County to small rural communities like Starr County, Texas. That accounts for much of the variety in how registration rolls are maintained.

“Often it’s an administrative or technical issue,” Pew’s Becker said. “People are not deliberately trying to remove people. They have a very hard job. They have a legitimate interest to make sure we are not spending taxpayer money to send information to people who are not voters.

“You want to make sure all eligible voters have a chance to vote and only eligible voters register,” Becker said. “Every eligible voter who wants to vote should have one record in one state list. That should be the goal. That’s an attainable goal.”

(Editor’s Note: Emily L. Mahoney, Hillary Davis and Jimmy Miller contributed to this report.)