With the advent of the sharing economy, new industries are disrupting traditional economies. At least one Oklahoma City councilman would like to see action on the growing regulatory dilemma posed by the popular home-sharing site Airbnb.

Existing city regulations require potential Airbnb hosts to attend a public hearing and purchase $2,700 bed-and-breakfast permits, a threshold that NonDoc could not identify any Oklahoma City host as having met. As a result, Airbnb hosts here leave themselves open to code violation notices from the city.

“I can always sympathize with people’s plights and understand why they would want to do something [like host on Airbnb],” said Laura Yates, municipal counselor with the City. “But that doesn’t excuse them from following the law.”

The sharing economy emphasizes temporary ownership over outright ownership. Examples include Zipcar, a car-sharing service, and GetMyBoat, a boat-sharing service. Locally, Oklahoma has so far been amenable to the ride-sharing economy with a new law for services like Uber and Lyft that went into effect July 1. That law classifies such entities as “transportation network companies” and sets up a regulatory framework for them to operate legally in Oklahoma.

While Oklahoma has regulated the new business opportunities that ride sharing presents, home sharing is beginning to pose some problems.

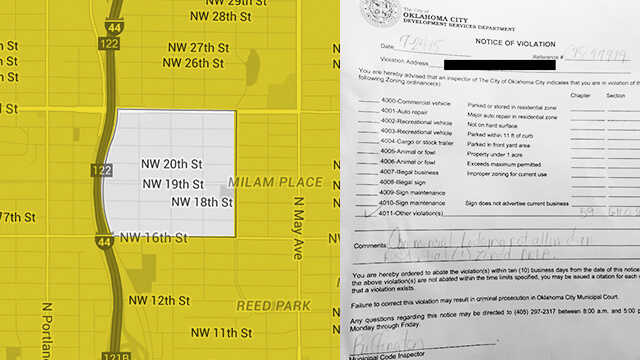

According to Kristy Yager, OKC director of public information and marketing, exactly three addresses have received Airbnb-related complaints for operating commercial lodging in a residential zone. Two were in the Linwood Place neighborhood, while another was in the Quail Creek neighborhood. Complaints were lodged by residents in those neighborhoods and then enforced by the City.

In the case of Quail Creek, an inspector from the Development Services Division presented the violation to Yates, the municipal counselor. After confirming the City had probable cause, Yates filed charges against the residents at the address listed.

With regard to the Linwood Place violations, Kathy Edzards, president of the Linwood Place Neighborhood Association, said in an email that both city codes and Linwood Place “urban conservation codes” are important.

“We, the Linwood Place Neighborhood Association, support the codes as stated and enforced by OKC,” she said.

NonDoc reached out to multiple Airbnb hosts, including one in Linwood Place who had received a city citation. He was unwilling to speak on the record for fear of complicating or ruining his ability for future hosting.

Airbnb and its potential impact on OKC

San Francisco-based Airbnb, which bills itself as “the easiest way for people to monetize their extra space,” began in 2008. It has grown to become the third-largest venture capital-funded startup, with $25 billion invested so far (Uber leads the top three with $51 billion, followed relatively closely by Chinese smartphone producer Xiaomi with $46 billion).

The service works like this: Users with extra rooms or homes to rent create a profile and post information about their space, including size, amenities, rules and cost. Travelers looking for accommodations then search those profiles to find a vacation rental that suits their needs. In the background, Airbnb takes a percentage off the top of each lodging rate.

City councilman Pete White said the council has recently discussed the issue of Airbnb hosting and its regulatory challenges.

“I personally think we ought to address it,” White said of the regulatory dilemma facing those who seek to host from Airbnb.

According to a story published Aug. 18 in The Journal Record, OKC officials are concerned that Airbnb use means the City misses out on revenue from its 5.5 percent lodging tax on hotels and motels.

How much money is changing hands in Oklahoma City by Airbnb, and how much potential lodging-tax revenue is the City losing to unregulated Airbnb hosts? The following is a back-of-an-envelope-type estimation.

On Aug. 8, Airbnb returned 149 listings for a single traveler with no dates specified in Oklahoma City: 91 offered an entire home for rent, 55 offered only a private room or rooms, and three offered shared rooms. These figures change according to the availability of rooms on any given day, but $88 was the average rate across all OKC listings at that time and on that day. By Aug. 20, the availability of lodging had fallen to only 59 units with an average of $67 per guest.

If 90 rentals (149 minus 59) were occupied during the course of 12 days in August, and hosts were charging an average of $77.50 (the average of the two observed rates) per guest per day, then, assuming each rental only had one guest, the cumulative host revenue during those 12 days could amount to a minimum of $83,700. Airbnb takes a 3 percent host service fee to cover the costs of payment processing within their system, so total host revenue is actually more like $81,189 in this scenario.

With the 5.5 percent lodging tax, the City would be missing out on a potential $4,465.40 in tax revenue just for the 12 days in this example.

The bright side for the City is that Airbnb appears amenable to making host revenue available to local lodging taxes. In 10 U.S. cities and one entire state (North Carolina), lodging taxes are collected to fulfill various transient lodging, transient occupancy, hotel accommodation and various other tax classifications.

Airbnb nation

The controversy between Airbnb hosts and city officials has played out or remains ongoing in other cities. For example, in Charleston, S.C., city officials went so far as posing online as potential Airbnb guests, contacting a host to inquire about room availability and showing up at the host’s home hours later to issue a fine in the amount of $1,092. Officials there cite neighborhood preservation as justification for their tactics.

In Austin, pro-Airbnb factions have taken the offensive, as local media there offer tips for beating what they consider overreach on the part of city enforcement during the SXSW media festival. Tips include hosts hiding their Airbnb “street view” and using word of mouth to rent to short-term tenants.

In yet another dimension of the problems home sharing is causing unprepared municipalities, citizens in the liberal beach town of Venice, Calif., are actually protesting against Airbnb use, as owners of apartment complexes there have found it more profitable to rent units on a short-term basis in the popular vacation destination. Locals feel cheated out of housing availability in an otherwise rent-controlled area. In Venice-adjacent Santa Monica, the ability to legally host through Airbnb has been outlawed unless guests stay a full month.

Regardless of any new laws or increased enforcement that aim to address OKC’s home-sharing economy, people will likely continue to do what they can to make money and save money. Homeowners seeking to supplement their income through Airbnb will continue renting out their properties, and travelers seeking to save on lodging will continue to book reservations with them.

White, the OKC councilman, emphasized that code enforcement is complaint-driven, meaning inspectors don’t drive around looking for tall grass and weeds, much less play “gotcha” on Airbnb hosts through the website’s listings.

“When regulation comes, it needs to be done fairly,” he said. ”I think a $2,000 annual fee is too much for someone who only has one or two rooms to rent.”

Likewise, he said, lodging businesses have been operating long before Airbnb’s origins, and it is unfair for them to continue operating within regulations while unfettered competition threatens their market.