The first 2016 Democratic presidential debate was dominated by passionate policy promises around populist issues that fueled Barack Obama’s coalition of excited voters in 2008: young voters, minorities, urban liberals, moderate independents and the labor movement.

You could say it was all about that base.

Democrats are confident electorate demographics in presidential years still favor them, despite the history of incumbent parties struggling to hold the White House after eight years of control.

Some quick takes on the performances Tuesday:

Hillary Clinton

The most experienced debater of the candidates, Clinton hit her mark by playing it safe and mostly avoiding the mud with her opponents. They have struggled to get traction, so why risk slipping in the mud herself? There were some spots where Clinton took on Sen. Bernie Sanders, most notably on a vote about gun manufacturer liability. Sanders has emerged as a long-term irritant to Clinton’s nomination pathway, given his fundraising success. If Vice President Joe Biden jumps in, he could further split the voter and donor base.

I thought the most intriguing moment of tonight’s debate was the tag-team attempt by Sanders and former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley on Clinton’s perceived vulnerability regarding her support of the Glass-Steagall Act in the U.S. Senate. Both of these opponents itched to draw contrasts with her. Sanders claimed the act enables “fraud as a business model” on Wall Street, and he strategically pointed out that he fought Alan Greenspan and her husband and former President Bill Clinton over the legislation.

Clinton replied by trying to have it both ways, not wanting to reinstitute the act but claiming she is tough by pushing to prosecute bank CEOs. She said she clamped down on the banks in 2009 by telling them to “cut it out” with the homeowner foreclosures, an appeal that appeared soft in comparison to Sanders’ voracious characterizations.

O’Malley was next to pin support of Glass-Steagall on Clinton as an epic battle between “protecting a main street economy from Wall Street greed.” That exchange stood out in this debate because it focused on a core issue among the Democratic base, and one where her opponents can draw valid contrasts. On many other red meat issues for progressives, there is little difference between her and her primary opponents.

Nonetheless, Clinton didn’t slip up enough to give any of her opponents room to become a near-term threat. Her larger problem, though, lies in whether enough Democratic voters calculate the general election optics. Is she untrustworthy enough to put the White House out of reach? How does that compare to Sanders’ potential general election liabilities? It remains to be seen if Democratic primary voters, rather than general election voters, will actually think along those lines. The GOP and national media are driving the narrative nonetheless.

Clinton closed in a presidential manner. She focused on vision for a better future, and — borrowing from Bill — she relayed a story from her mom about being knocked down, then getting right back up.

This was the most direct example of her core strategy: honor Obama’s record in a restrained manner to appeal to the base, but suggest she and “we” can do better, which is the general election message. Of Obama, she said he “got us standing again” after the Bush recession, but we are not “running” as we should be.

That’s some strong Clinton triangulation right there.

Bernie Sanders

In a weird way, Sanders seemed at times like a front-runner having to fend off attacks. As the candidate with the most momentum and the most passionate base of supporters, he was the target for O’Malley, who is not very distinguishable from Sanders on policy standpoints. O’Malley and the others, including Clinton, seemed unable to make a dent in Sanders or cause him to stumble. He seemed to be the most comfortable candidate on the stage, even if Clinton is the most polished debater. As someone who seems considerably comfortable with who he is as a politician, Sanders has an attractive advantage in a political world now dominated by attention-seeking candidates eager for approval. Sanders probably won’t win the nomination, but you also cannot accuse him of trying to pander to get there. He is who he is and doesn’t appear to take disagreement personally.

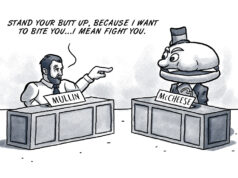

The debate’s most talked-about moment will probably be when Sanders defended Clinton on her e-mail problem. It was a genuine gesture, but also a shrewd move by the Vermont senator because it comes off as a dedication to take on the GOP, even if it means defending a primary opponent who leads in the polls. In the eyes of the party base, this Democratic loyalty only enhances the emotional support of Sanders’ volunteers and low-dollar donors. This also maintains goodwill with Clinton supporters if the email problem evolves into a scandal, and derails her campaign, leaving Sanders as an untainted second option. As one of my favorite writers tweeted in a homage to Sanders’ Jewish faith, it sure was a “mitzvah,” or an act of kindness.

Sanders’ closing statement wasn’t remarkable, but it didn’t have to be — his overall performance was solid. He will likely come out of this debate with some growth in support.

Martin O’Malley

O’Malley is sharp and impressive, but you don’t get the sense he can generate much movement because there isn’t “room” for him in the field. He went on the offensive against Sanders owing to this dilemma and because they are both vying for the same fervent, progressive, populist vote that appears to disapprove of Clinton.

O’Malley had the best closing statement, and the eloquence that most resembled charismatic Democratic candidates of the recent past (Obama in 2008 and Bill Clinton in 1992). He made a large-D Democratic Party appeal of unity at the end. You get the feeling he would be the frontrunner if Clinton chose not to run. He would be a seemingly more-electable progressive than Sanders. However, at present, minus any major surprise, O”Malley looks to remain in a distant third place. Maybe he could heed my out-of-the-box advice?

Jim Webb

The former senator from Virginia was once considered a rising star in the Democratic Party after his upset win over George “Macaca” Allen in 2006. On paper, he has an apparent appeal in a close general election where uneasy hawkish GOP moderate voters would have somewhere to turn if Ben Carson is just too “out there.” The problem for Webb is that a more purist Democratic primary electorate chooses the nominee, not moderate swing voters. Although he would probably be a decent president, he is considerably unexciting as a candidate in a field of stronger candidates.

Lincoln Chaffee

Like Webb, Chaffee has a pre-2008 appeal when the electorate was more closely divided and made up of more moderate swing voters. But the current presidential electorate is driven more by demographics and the turnout of the base coalition, which was a factor behind Karl Rove’s risky pick of Sarah Palin in 2008. Chaffee seems the most out of place on the stage. It is a toss-up whether he or Webb drops out first.

It’s late, so if you need a bigger conclusion than that, turn on a 24-hour news channel and tape your eyelids open.

Otherwise, I’ll leave you with Bernie’s “mitzvah” to Hillary.

https://youtu.be/_otSN69KkyU