“Before court reform, judges ran in open elections—anybody could run for office. They were totally dependent on lawyers’ contributions to their campaigns. It was a rotten political system.”

— Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice Marian P. Opala

In Oklahoma, the solemn vow of “Never again” has a shelf life of 50 years.

In 1965, Oklahoma endured the worst judicial scandal in American history when three longtime Oklahoma Supreme Court Justices were revealed to have taken bribes in exchange for favorable decisions on appeals pending before the court. Although shocking when finally dragged into the sunlight, the scandal had been a long time coming. Oklahoma’s legal and business communities had whispered — not for years, but for decades — that justice was for sale in Oklahoma.

They were not mistaken.

One of the disgraced judges, Nelson S. Corn, inadvertently but aptly captured this pervasive atmosphere of casual corruption in Oklahoma: When the elderly jurist was asked by investigators whether there was any year out of his three decades on the Oklahoma Supreme Court in which he did not take a bribe, he dismissively snapped, “Well, I don’t know!”

To our great shame, that is how things used to be in Oklahoma. To our great credit, things are not that way anymore — and never were again after our national disgrace a half-century ago. Since that time, Oklahoma’s rigorous merit-based system for appointing judges, as implemented through a bipartisan and ecumenical Judicial Nominating Commission, has ensured that only the most professionally qualified and ethically sound candidates will serve on the state bench. The bad old days of the Oklahoma judicial system, it seemed, had been banished forever.

HJR 1037 a ‘dangerous’ proposal

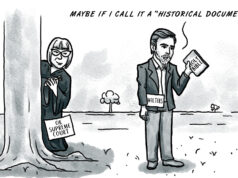

That celebration may yet prove premature. This year, the Oklahoma Legislature will consider at least twenty bills intended to radically alter the selection, composition, and tenure of Oklahoma’s judges — particularly appellate judges. All of the bills are misguided, but one is truly dangerous: House Joint Resolution 1037 (HJR 1037), which would amend the Oklahoma Constitution by abolishing the Judicial Nominating Commission and returning Oklahoma to the old system of popularly electing all appeals-court judges.

The legislation is authored by Rep. Kevin Calvey (R-OKC), whose most recent foray into legal commentary came last year, when he publicly expressed his wish to “douse [him]self in gasoline and set [him]self on fire” in front of the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s building as a protest against the “evil” of the Court. With HJR 1037, it appears that Rep. Calvey has now transferred his yearning for destructive immolation to our judicial system as a whole. And even many reasonable and responsible voices —including some within the Oklahoma bar — are clamoring for the gasoline and matches.

A painful thing to acknowledge

How did we get here? Oklahoma’s unique political history explains much of the present dysfunction.

In the wake of the Court scandal in the 1960s, Oklahomans quickly and collectively realized that the problem of judicial corruption was far bigger than the simple greed of a coterie of rogue judges. Our system of selecting the judiciary itself was to blame. And this was a painful thing to acknowledge, for it required a still-fledgling state to challenge the received wisdom of its founders. Oklahoma’s 1907 Constitution was (and largely remains) a robustly populist document that faithfully reflected a prevailing frontier philosophy exemplified by keen distrust of centralized executive and corporate power.

To the authors of the Oklahoma Constitution, this pugnacious grassroots impulse logically extended to the way in which Oklahomans should choose their judges. From statehood, the Oklahoma judiciary would thus be elected by popular vote on a partisan ticket in the same manner as candidates for executive and legislative office, founders held.

Except here it did not work. Elections required campaigning. Campaigning demanded campaign contributions. Campaign contributions begat favors to contributors; the larger the contributions received, the more favors to be dispensed. Money touched everything, and partisanship tainted all. In 1965, the system collapsed.

Judicial Nominating Commission to the rescue

Oklahoma rehabilitated its court system and repaired its national reputation only through decisive action. In 1967, following admirable efforts by the Legislature, Oklahoma voters amended the state Constitution to create the Judicial Nominating Commission. In an instant, the people of Oklahoma eliminated from the sphere of the Oklahoma appellate courts both partisanship and the distractions of political campaigning. Above all, they removed the impediment of ethical compromises and divided loyalties, both large and small, that in a politicized electoral system will inevitably erode the ability of judges to apply the rule of law fairly, impartially, and independently. The system worked: No allegations of bribery have been made against an Oklahoma judge since the inception of the Judicial Nominating Commission.

The Oklahomans of 1967 succeeded where the Oklahomans of 1907 had erred. Judges — especially appellate judges — are not and should not be politicians. Although they serve within a coordinate branch of government, their rulings depend on their ability to stand apart from — and above — the frenzies and whims of the moment. This essential detachment allows our judges to arrive at correct, but politically unpopular, decisions. It safeguards the constitutional rights of minorities in an often-hostile majoritarian system. It guarantees a stable legal environment to business owners, who enter into contracts with the expectation that their agreements will be enforced in a neutral and consistent manner. And it shields the rule of law from influence and encroachment by zealots and opportunists in other branches of government — and those who fund them.

Preserve the JNC 50 years later

Armed with the focus-group-approved buzzword of “accountability,” powerful special interests in Oklahoma want to do away with the Judicial Nominating Commission this year. These groups claim to act out of solicitude for the will of the people. But their concern for the popular will exists only to the extent they believe they can control it. That control comes in the form of money and, more to the point, the unfettered free-for-all of campaign dollars in a post-Citizens United world.

The abolition of the Judicial Nominating Commission and a return to popular election of appellate judges would undo 50 years of judicial independence in Oklahoma. It is time to renew our vow: Never again.