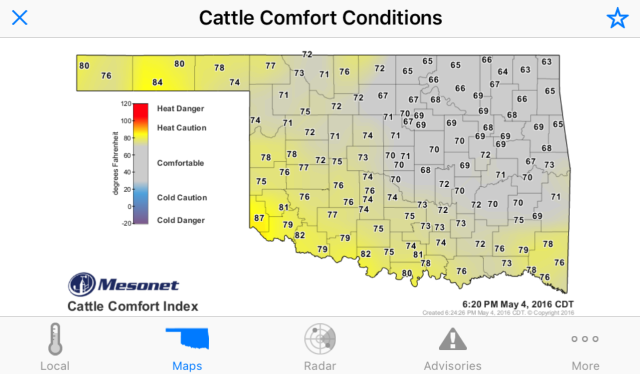

Is your pecan tree at risk for scab? Are your cattle comfortable? Are your peanuts protected?

Believe it or not, there’s an app for all of that.

The Oklahoma Mesonet can tell you when to look for peanut leaf spot. It can tell you how hot the soil is two feet underground, and how much rain has fallen in the last year.

Of course, it can also show you the temperature or the radar.

The Mesonet itself is a network of 120 towers spread across all 77 Oklahoma counties. Each Mesonet tower records atmospheric data every five minutes. From temperature to humidity, precipitation to wind, the towers send a constant supply of valuable data to the National Weather Center, which in turn operates the Mesonet app.

‘Like no other network could’

When severe weather threatens and eyes across Oklahoma become glued to local television channels, eyes at the National Weather Center watch the Mesonet.

Speaking last Tuesday morning, Mesonet manager Chris Fiebrich talked through the Mesonet’s role in monitoring the day’s atmospheric developments. The forecast had called for heavy storms in the afternoon with large hail and the potential for tornadoes.

“In Oklahoma, the forecasters will be able to, throughout the day, really monitor things like the dry line, which is where, typically, convection will initiate,” Fiebrich said. “If you’re behind the dry line, your chance of tornadoes is virtually zero. Right ahead of the dry line, you have a maximum chance. The Mesonet is going to be tracking that like no other network could.”

The Mesonet’s name comes from a combination of “mesoscale” and “network.” According to the Mesonet website, “thunderstorms, wind gusts, heatbursts, and drylines are examples of mesoscale events.”

Of farmers and meteorologists

In operation since 1994, the Mesonet was created as a cooperative project between the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University. Fiebrich said OU’s need for accurate meteorological data coupled with OSU’s interest in agricultural planning brought the Mesonet to life.

“Through [OSU’s] research, then we here [at OU] create a model and write software code to ingest the Mesonet data and they use their research to make products for real-life growers and producers out there,” he said.

Fiebrich noted that, although the Mesonet is headquartered in Norman, the two universities share it equally, with OSU faculty members even working at the National Weather Center in Norman.

The Mesonet’s practical uses extend far past weather, agriculture and the minutiae of cattle comfort. Fiebrich mentioned Ok-First, a program started in 1996 that has trained more than 1,000 emergency managers across the state to use Mesonet data for emergency preparedness. The Mesonet also plays a major role in Oklahoma fire safety.

“Fire is largely affected by weather,” Fiebrich said. “The wind, the solar radiation, the relative humidity — all those things determine the likelihood that a fire will ignite, and also determine how fast the fire will spread.”

‘Pretty darn accurate for where I am’

OU meteorology major Monique Sellers, who works regularly with the Mesonet, said the network and its free app can help average Oklahomans as they plan their day.

“It’s a habit for me in the morning,” she said. “The first thing I do is check the weather just to see how I need to dress that day. Do I need to wear my rain boots, or is it going to be crazy windy? With the Oklahoma Mesonet, I know there’s a site within the next five miles from me, and I know that weather’s going to be pretty darn accurate for where I am.”

Beyond the day-to-day weather monitoring, Fiebrich said, the Oklahoma Mesonet has had a tremendous impact on meteorology and climatology research, not only in Oklahoma but around the world.

“We’re always kind of amazed at the applications that pop up,” he said, adding that he’s glad the app is free to the public. “We want Oklahoma citizens to be able to get free access to everything we provide. We knew that when we started the Mesonet, if we didn’t get the data in the hands of the users, it would not fulfill our goals in any way.”

He said the Mesonet’s unparalleled data trove is beginning to yield valuable insights for researchers across the globe who want to parse its findings.

Hundreds of peer-reviewed journal articles have cited Mesonet data, Fiebrich said. It’s the kind of data that can only come from taking 120 readings 288 times a day for 22 years.

“With this data set, as the years continue and the archive grows, we’re going to be able to detect things that are going to be really high-quality,” he said. “Scientific research can be done here. And you only get that by having a very long record.”

Sellers, too, was optimistic about the future of the Mesonet.

“The possibilities really are endless for what the reach of the Mesonet can be.”