What thought comes to mind when someone tells you they went to Harvard? How about the University of Oklahoma? Or Oklahoma State University? Or the University of Central Oklahoma? What about Vatterott College?

If the latter causes your mind to go blank or makes you feel like there is no comparison with the others, you’re probably not alone.

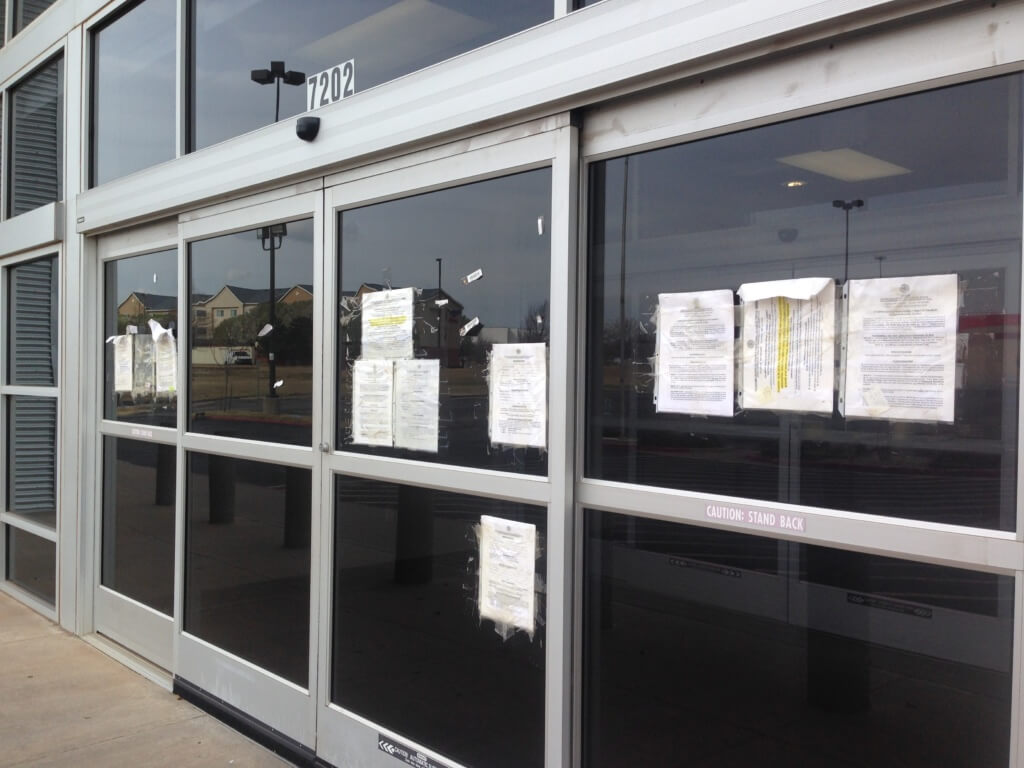

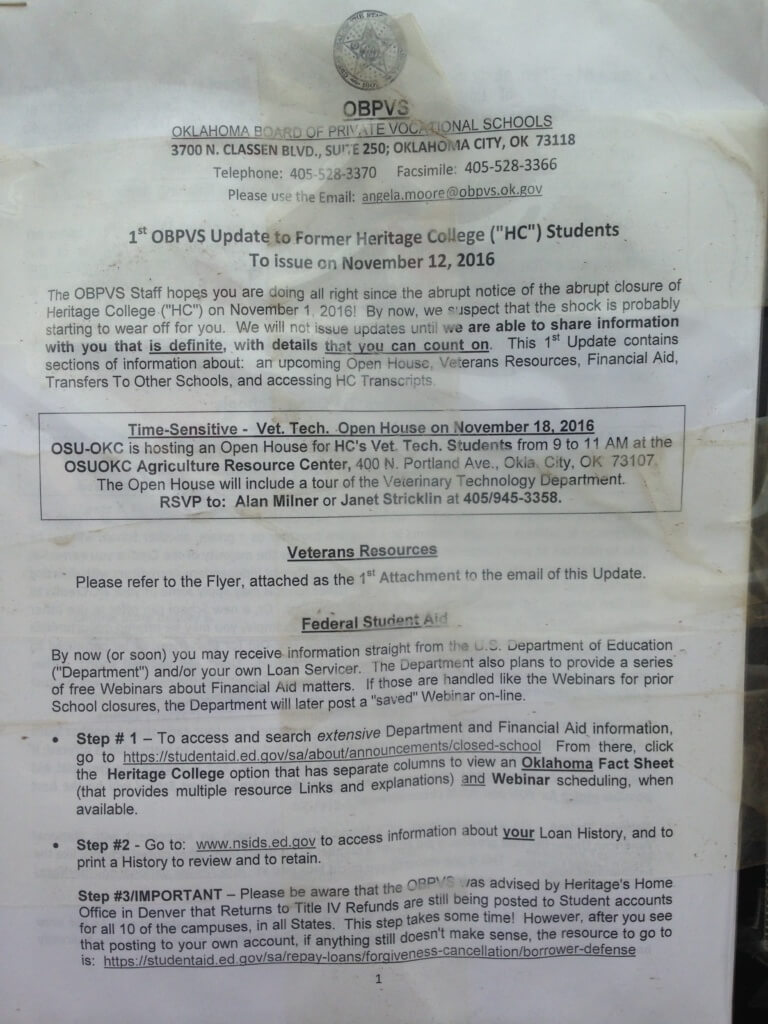

Whether it is Heritage College, Brown Mackie College, ITT Technical Institute or Wright Career College, people are familiar with the names of these private vo-tech schools. With ubiquitous commercials on daytime TV, they have robust marketing efforts and a moderate standing in the public consciousness. What these four have in common beyond name recognition, however, is that they have all closed their doors for good. Now, Vatterott College is showing signs of potential problems, and students are looking for answers.

The vo-tech appeal is real …

Many of these for-profit vo-tech schools — and nonprofit vo-techs, as is the case with some of them — started off as alternatives for prospective students who didn’t want to spend four to 12 years of their lives attending class for the possibility of an interview at a mid-level company that may or may not be interested in hiring them. Alternatively, vo-tech institutions carry appeal as places that provide opportunities for people of all ages and skills to identify a specific type of job they would like to pursue and then take coursework built around that industry.

Want to be a massage therapist? Why go to a four-year college when you can enroll at Central State Beauty and Wellness College? Does your family insist that you would make a great hairstylist? Check out JB’s Hair Design and Barber College.

… but so are the problems

Unfortunately for many of these schools, they rarely find themselves on the positive end of media coverage. Especially in Oklahoma, vocational schools haven’t exactly been making headlines due to the success of their graduates or job-placement rates. Instead, the reports focus on issues such as accreditation problems or school shutdowns.

A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that students who graduate from for-profit colleges and universities tend to experience a decline in earnings several years after attending as compared to prior to going to school. For many, this is combined with increased debt, usually as a direct result of attending school.

The costs of attending these schools is significant, and many of the students who enroll are in need of financial assistance. About 96 percent of students take out a student loan. At the same time, an estimated 86 percent of the revenue at for-profit colleges originates from federal taxpayer dollars.

Heritage College, which closed the doors at all of its campuses last year, charged an average of $23,347 per student for tuition and fees in during the 2015-2016 school year, with other costs including $1,648 for books and supplies. Based on data from the National Center for Education Statistics, total enrollment at the school was 492, with women representing 84 percent of students.

What ‘job placement’ really means

Students who go to these schools may be looking for a quicker path to getting their career started, but there is little evidence that there are enough success stories to make it worth it. Some schools show a high job-placement rate while others show less flattering numbers.

What the numbers don’t necessarily talk about is what job placement actually means. A person may graduate with the intentions of becoming a medical technician but never actually elevates beyond janitorial services at a medical company. Did they actually need college classes for that position? Probably not. But the college gets to brag that they helped place that graduate into a job in their chosen field.

You can’t help but feel for the students who go to these schools and find difficulties in locking down a job in the field that mirrors their education. It is even easier to sympathize with those who attend school for months or even years and suddenly find themselves with memories of wasted time when the college decides to shut down its doors prior to graduation. One wonders just how difficult it is for someone to get hired when the school that educated them is no longer around.

Reputation seems to precede itself with many of these schools, however, and one has to ask if people truly understand the risks that are associated with attending.

Clearly something amiss

It is easy to understand why the reputation of these “outlier” schools has evolved into what it is. Multiple obvious errors and mistakes can be seen in an overview document the Oklahoma Board of Private Vocational Schools provided to an Oklahoma State Senate interim study in 2015. Even the website for Oklahoma’s private vocational schools’ oversight agency seems embarrassingly lacking.

The future of for-profit colleges and universities may be strong for some and weak for others, but there is clearly something amiss with the system. When so many institutions are suddenly closing their doors, students are left holding little more than debt on their loans.

Until something changes, the public has more than enough reason to be skeptical as to the true value of these schools’ degrees.