More than ever, the changing realities of online content distribution are putting journalism organizations under the gun. Primarily, I’m talking about the need for publications to “boost” articles they post on Facebook to maximize potential site traffic.

For online publications, site traffic ultimately generates advertising revenue, but more and more of that revenue must be spent on Facebook to gain site traffic. It’s the classic snake-eating-its-tail scenario, only you can hear Mark Zuckerberg cackling maniacally while he watches the serpent sizzle on his barbecue grill.

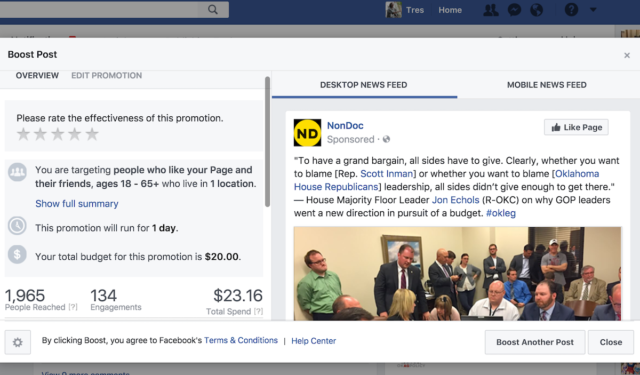

In short, Facebook has online news sources like NonDoc by the balls, and when we have a click-getting story that we’d like to maximize, we often spend $5 to $20 “boosting” its post on our Facebook page. When we do that, Facebook displays the gray word “sponsored” under our page’s title. I have often wondered what readers think of that designation. Do they understand what “sponsored” means in this instance? Do they think someone else paid for the story to run? (At NonDoc, we call that type of deal Funded Content, for what it’s worth, and we designate #funded on any Facebook posts of such advertorials.)

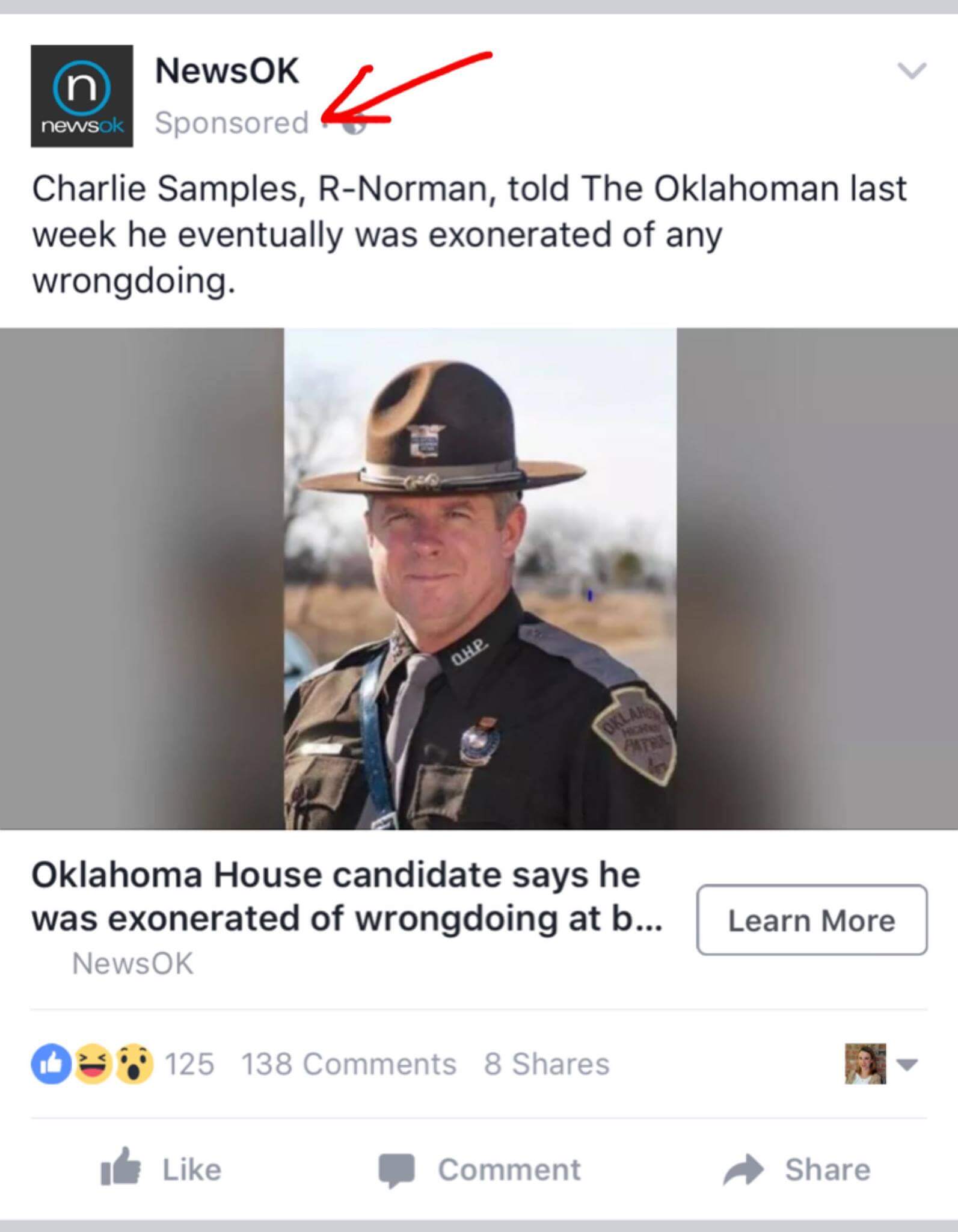

But Thursday, I noticed Facebook’s gray “sponsored” bug had irked some local politicos on a NewsOK story. In particular, the Oklahoma Democratic Party’s former executive director had posted a screenshot showing this political story about a state trooper “sex party” had been boosted by NewsOK on its Facebook page.

Now working as a political consultant, Sarah Baker added this explanation of her concerns:

So now the Oklahoman is paying to promote Republican candidates? Will they be reporting this as an in-kind contribution to Samples’ campaign?

I’m not interested in a discussion on what Samples did at this moment but what greatly concerns me is the very possible campaign contribution NewsOK is making!

Dozens of comments followed, with a plurality criticizing The Oklahoman and other media for showing their “true colors” and supposedly violating Oklahoma Ethics Commission rules.

Against my better judgment, I chimed in, attempting to relay what knowledge I’ve gained about web journalism, Facebook boosting and media ethics since NonDoc launched in September 2015. As an editor who struggles to get his site’s content to reach our full cadre of social media followers, I understood the process, potential and pitfalls of boosting stories.

Budgeting for boosts

Facebook’s organic reach percentage has plummeted this decade as the social media giant makes more and more revenue by setting up back-end paywalls.

“Congratulations, you’ve got 50,000 page followers! You want them to see your post from today? Well, we’ll show it to 2,500 of them for free, but if you want it to reach more, you’re going to have to pay.”

With organic reach dropping from nearly 20 percent to less than 5 percent and with journalism outfits relying heavily on Facebook for online news exposure, media companies now must budget for boosts.

In our small newsroom, I usually pose boosting decisions out loud before sending a hard-earned $8 back to our Social Overlords. The only thing that ever gives us pause is whether an article is getting enough shares to make the boost pointless or whether the article deals with such a touchy subject that we don’t want to be seen as promoting it commercially.

And, boy, can politics be touchy.

The ‘press exemption’

To that end, we have only recently begun boosting political stories at all. Fearing the perception that we favor one side over another on any controversial matter, we have often avoided boosting a piece that we knew would perform well.

But at some point this legislative session, my opinion on the matter changed. Boosting, I figured, has become such a digital distribution necessity that not boosting our popular political stories was akin to cutting our ethical noses off to spite our moral faces. Besides, no one had even noticed or said anything about the little gray “sponsored” bug.

Until this week.

With criticism pouring in that NewsOK was unlawfully using “electioneering communications” or “independent expenditures” to promote Charlie Samples — who, for the record, looks like a buffoon in the piece — I called the Oklahoma Ethics Commission to ask for guidance.

After an amusing battle with their malfunctioning phone system, I was directed to the agency’s laws and opinions, which specifically explain the “press exemption” in a 2015 advisory opinion:

The Ethics Commission recognizes what is commonly known as the “press exemption” for contributions and expenditures. Generally, a contribution or expenditure does not include any news story, commentary, or editorial distributed through the facilities of any broadcasting station, newspaper, magazine, or other periodical publication, unless such facilities are owned or controlled by any political party, political action committee, candidate, candidate committee or ballot measure committee.

I’m no lawyer, but a publication’s Facebook page surely counts as one its “facilities” for distribution.

‘It’s almost an ad’

While I waited for Baker to return my call, conservative radio host and political consultant Chad Alexander rang my telephone. He had chimed in on the Facebook discussion as well.

“Social networking has brought us to a whole new level of asking questions that we haven’t asked before,” Alexander said by phone. “There weren’t enough people on Facebook in 2010 who were old enough to vote, but in 2017 it’s a different ballgame.”

He agreed that media have and need protections in the law beyond what other corporate entities can do, but he also said the type of reporting being boosted — and exactly where that boost is targeted — send messages intentionally or not.

“This is election coverage, which is different than policy coverage,” Alexander said. “When you’re writing about an election, it’s almost an ad when you sponsor it.”

Baker felt similarly.

“Spending money to boost that can be viewed by many as an in-kind contribution,” she said by phone. “Who it is an in-kind contribution to — especially in this kind of situation — is up for debate. When there is an array of articles to boost, what is the motivation of one that is related to one particular candidate?”

I suggested the article’s inclusion of the phrase “sex party” likely influenced that decision. Baker agreed, but she said campaign scenarios deserved more consideration from an editorial perspective.

“There needs to be a clear understanding of boundaries as it relates to political candidates,” Baker said.

Public mistrust of media

While it’s good to know Oklahoma’s campaign ethics laws don’t appear to run afoul of a journalism organization’s business efforts, we’re still left to question how the public will perceive any given boosted political coverage.

The frustration expressed on Facebook about NewsOK’s boosted story showcases the massive mistrust the public currently has for media. It also highlights how the business processes we employ as media companies are often unclear to readers in general.

So will we boost our next thought-provoking partisan commentary? Will we boost our next big story about Oklahoma politics?

Thank goodness it’s the weekend and we can think it through thoroughly before clicking “boost.”