LAUSANNE, Switzerland – Some years ago, I went on vacation to Bermuda. It was meant to be a week of lying on the beach, snorkeling, scuba diving and drinking a healthy amount of rum.

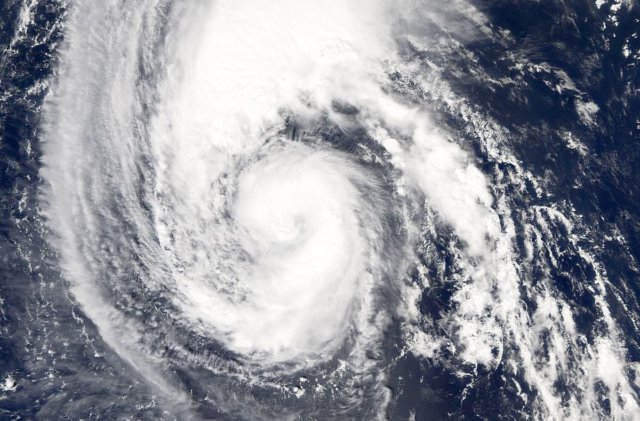

A week before my trip, a hurricane began forming in the Atlantic Ocean. It got organized and began a leisurely crawl in the general direction of the U.S. east coast. It was looking to be no bigger than a Category 1, meaning some high winds and a bit of rain, and was unlikely to hit Bermuda anyway. With the choice of canceling the vacation or still going, I decided to take my chances.

My father, who is a meteorologist, thought I was crazy. He didn’t understand why I didn’t cancel the vacation all together. He consulted the forecasts and asked his hurricane-expert friends for their opinions. One expert predicted it would pass west of Bermuda while another said it would definitely pas east and be no stronger than Category 1.

In the end, Hurricane Florence picked up strength and made nearly a direct hit on the island as a Category 2.

While the one I lived through was mild compared to the devastating and tragic storms that have hit the U.S. this year, the experience was powerful enough to be etched in my mind forever.

Riding the storm out

I was one of only five passengers on the plane ride into Bermuda, while the line for people leaving contained several hundred. That was my first indication that I might have made a bad decision.

Immediately after arriving, we went to the supermarket and bought everything we would need to survive being trapped indoors for 36 hours with no electricity; namely water, food, flashlights, batteries, candles and a lot of wine.

All over the island, Bermudians in their Bermuda shorts were cheerfully nailing boards to their shop windows and joking with their neighbors, as if they did this all the time. That reassured me significantly.

The house I stayed in was on a hill far away from the beach, so we had little fear of flooding. Buildings in Bermuda are required by law to withstand winds of 100 mph and are mostly built from stone or concrete. The owner, who lived next door, came by and nailed boards to the upstairs windows and took all the plants and chairs off the porch and balcony.

Around 5 p.m. on Sunday, Sept. 10, 2006, the wind picked up and it started to storm, with rain, thunder and lightning. We sat in the interior bathroom away from all exterior doors and windows, and we played cards to keep ourselves amused. The storm steadily gained strength over the next 12 hours. Just before 5 a.m. Monday, the power went out.

I discovered that the most disconcerting part of riding out a hurricane is that you have no idea what’s going on outside because you can’t see it. Most windows have been boarded up. Other glass parts, such as patio doors, have metal sliding shutters that are wound down. If any windows remain uncovered, you stay as far away from them as possible, ideally with several walls between you and the outside. All you have is your ears and the TV, radio and internet to tell you what’s going on outside. Once the power goes out and the cell towers fall down, you have only your ears. You hear the wind and the rain but have no idea what damage it’s doing to the structures and trees around you. The muffled creaks and thumps that shudder outside take on a new level of disconcerting when you can’t visually match the source of the noise and are left to guess what it might be.

Sometime early the next morning, when Hurricane Florence was still many hours from being past us, the metal railing on the second-floor balcony began to detach from its base. We didn’t know this of course until the owner of the apartment — to our great amazement — ventured outside with a friend and managed to tie a rope around the railing and attach it to the house. He was attempting to prevent it from blowing off and hitting something or someone below. It took one man’s strength alone just to open and close the balcony door.

Rare but devastating storms

After the initial adrenaline when the storm first arrived, waiting out the hurricane got somewhat boring. We were limited to our small bathroom, and after 12 hours of card games and idle banter, we were out of ideas to entertain ourselves. Sleep was difficult from the uncomfortableness of our shelter and the fear of not being able to react quickly if necessary.

Eventually, by the end of the afternoon Monday, the howling stopped and we ventured out to see the extent of the damage. Fortunately it was not nearly as bad as that caused by Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Irma.

There were tree branches everywhere, making the road more green than gray. As we walked around the island, a few roofs had tile damage and at least one shed had blown over, but beyond that, not much had happened. There were no injuries or deaths reported, and total damage was estimated at a mere $200,000. Clean up began immediately, with trucks picking their way slowly through the streets as workmen hoisted branches into the back. The power was out for around 36 hours, but overall, Bermuda was lucky.

Islands and nations that have prepared themselves through strict building codes and planning can fare reasonably well in hurricanes, at least up to Category 3. The Category 5 Hurricane Irma, however, passed over numerous islands in the Caribbean last week left greater destruction, strict building codes or not.

For those of us who have grown up in tornado alley, storms and their consequences are part of life. Luckily, as with severe tornadoes, severe hurricanes are rare, and even more rarely do the extreme ones make landfall with as much accuracy as Irma did.

As Texas, Florida, Cuba and the Caribbean islands start to pick up the pieces and rebuild their lives, we should all remember that while storms of this magnitude are catastrophic and unpredictable, they occur infrequently when plotted in the recorded history of hurricanes.