SEMINOLE — It was a fortune teller who informed 7-year-old Jasmine Dolores Careen Burchell of her future.

In 1941, Jasmine had but a few coins to spend at a country fair in Hornchurch, England, and, being one of three surviving daughters, she learned thriftiness from her mother, Lillian.

Lillian had married a scoundrel who not only caroused with other women but had the bad taste to leave his family on their own when he died of pneumonia.

Money wasn’t something to spend frivolously, but when Jasmine saw the colorful tent advertising “futures read,” she couldn’t resist.

“I walked in, and the gypsy said, ‘I don’t do the crystal ball. I read palms.’ So I held out my palm,” Jasmine recalled.

“You’ll make your fortune with your face,” the woman said. Jasmine immediately discounted that as untrue.

“You’ll live in America,” the fortune-teller added.

“Well, that’s rubbish,” Jasmine said. “I’m a good English girl.”

But Jasmine Burchell, who would later become Jasmine Moran, didn’t realize how true the fortune-teller’s words would be. Throughout her life, she faced hardships few would comprehend today, but used her looks, singing voice and talent to succeed on London stages as a chorus-line dancer and actress.

She would eventually catch the eye of a young Oklahoma serviceman and move to America.

She would also sculpt a lasting legacy in a small town called Seminole, creating not only a world-class children’s museum that attracts 70,000 visitors annually, but also funding and supporting the city’s animal shelter and other animal-related charities.

Yes, Jasmine Moran, Seminole’s 2008 Citizen of the Year, has made her mark on Oklahoma and the state’s families.

Those who know her say she’s got that special magic that allows her to connect with anyone, that makes people believe in her and the dreams she puts in place, and that makes everything she pursues successful.

Moran may be a diamond facet of Oklahoma’s who’s-who, but it’s clear the 83-year-old woman was forged in the fires of World War II England and in the bright lights of a stage.

Moran may be many things in America, but above all she was a girl who chose her own path and forced success to find her despite poverty, challenges and war.

A girl of ages

As Moran entered the children’s theater at the Jasmine Moran Children’s Museum on Nov. 1, the fiery energy that spurred her whole life was evident — despite what she called her “wheelie-dealie” walker and her tired, painful shuffle.

Moran, who had undergone heart surgery a month prior, cracked a few pithy comments in the hot toddy English accent she still carries, smiling under a coif of paper-white hair that floated around her face like baby’s breath.

Born May 7, 1934, in Romford, Essex, Moran was a giant baby, weighing just one ounce shy of 12 pounds. She came from a long line of strong women who had endured struggles. Her mother, born out of wedlock, was raised by her grandmother and earned her place in the world by mastering Scottish dance. She won numerous awards, so she instilled in her daughters the notion that hard work and talent could be their saving grace.

The women in Moran’s family were Gaelic, known as the faerie people, and they were famed for being able to see the future. Lillian Burchell, Moran’s mother, was adept at reading tea leaves.

“She saw once that the husband of her friend would die in a short period of time,” Moran said. “He died two weeks later from a heart condition no one knew about. She never touched the leaves after that.”

In 1939, England declared war on Germany, and the little aerodrome airstrip that sat right by the schoolhouse in Hornchurch became a strategic airbase. At 5 years old, Moran learned to recognize the sounds of bombs before they dropped. She was shot at on the way to school and practiced how to use gas masks.

“There was an open field by the schoolhouse, and the Germans would aim at anything moving in the field,” Moran said. “If you could make it to the little bridge over the stream, there were bushes you could hide in. I ran screaming to those bushes so many times.”

After the death of Moran’s “scoundrel” father, Lillian raised her three surviving children alone. Lillian held the Scottish dancing championship for several years in a row, and her three daughters inherited talent. Moran’s older sister, Helen, was an accomplished actress, while her younger sister, Davina, would become a well-respected ballerina in Canada.

Setting the stage

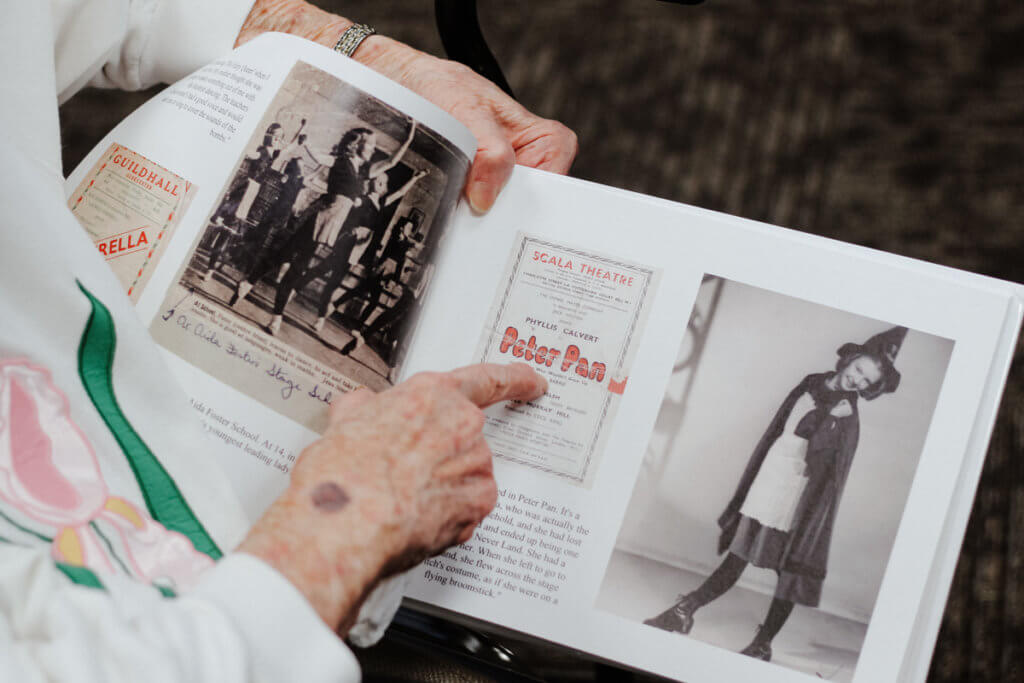

Moran’s singing voice and dancing ability would also take her far in the world. At age 2, Moran was dancing The Fairy-Queen and, by age 13, she performed as Maid Liza in the Scala Theatre’s presentation of Peter Pan.

In 1951, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific opened at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London’s West End. At 17, Moran became one of hundreds of girls competing for two spots in the musical.

“There were 120 girls for one of the roles and 120 girls for the second role,” Moran said. “I had three different tries for one of those roles. I was at the audition, and there were these types of girls who were so glamorous. They were 6-feet tall with small waists and big boobs, and I’m so short. I have scoliosis, which damaged my back, but we kept it at bay with dance, so I knew I had talent if talent is what they were looking for.”

Moran attended the first audition without her agent, and out of the 240 girls auditioning, she got the call back for a second all-day audition.

“I realized I had a chance. There was another girl there who was just so pretty, and they sent us home and told us they would call us in the morning if we made it through,” Moran said. “I didn’t get the call. Just as I was about to walk out of the house, the other girl called me and said, ‘Where are you?’ I said, ‘I didn’t get the call.’ She told me I was one of the three chosen, and I had better get there.”

Moran was chosen to play Ensign Pamela Whitmore. She graced the stage for 18 months. She and the other chorus line actresses, including Millicent Martin — who went on to become a television and screen actress, playing Daphne Moon’s mother on Frasier — became a tight-knit group of friends.

The boys in the show included a handsome (yet hairy) Scotsman who played the Muscle Man.

“He couldn’t sing at all. They wouldn’t allow him to. He had to shave his chest, too, because it was just awful,” Moran said. “He was such a nice man. Sean Connery was a very, very nice man.”

While working on South Pacific, Jasmine met a member of the U.S. Air Force, Melvin Moran, on a blind date.

“It was awful,” she said. “He was a twerp. He had eaten something and had to dart out of his car to throw up. I thought he was a twerp. But, he asked for another date, and it surprised me so much that I agreed. That date was wonderful.”

Jasmine fell in love, but she wasn’t sure if she loved Melvin enough to change her entire life and move to America. She was torn between a stage and screen career or becoming a loving wife in a different country.

“My mother told me, ‘If I were you, I’d marry him,’” Moran said. “So I did. I loved Oklahoma. In fact, I had auditioned for the musical Oklahoma!, so I was a little familiar with it. Melvin was an oilman, and Seminole was such a pretty little town. But the oil bust in the ‘80s nearly killed our little town.”

Years later on a family trip with her grandchildren to Flint, Michigan, Moran and her family stumbled upon a small museum dedicated to children.

“We had never seen a children’s museum before,” she said. “We always went to regular museums. You could see, but never touch, and I hated that. I’ve always been a touch person. This little museum had little old teapots and coffee pots and old radios that you could touch. We thought it was fascinating, so Melvin went out to the car to get his camera so we could take photographs.”

An idea began. Moran’s beloved and adopted home of Seminole was struggling in the wake of the oil bust.

Could a children’s museum bring the city back to life?

Leaving a legacy

“We saw the need for a children’s attraction in Seminole and in this area,” Jasmine Moran said. “Kids were coming home to empty houses, and we wanted to do something that stimulated their minds. We wanted new things instead of old things. We wanted new things that would advance and stimulate their brain, and that’s how it started.”

In 1988, Melvin and Jasmine brought together a diverse group of Seminole residents without telling them why.

“We invited either moms or educators, and we invited 15 to the meeting. Fourteen were friends of ours,” recalled Melvin.

The 15th person was Marci Donaho, a fourth-grade teacher who only attended because her school was serving beanie weenies that day, and she hated beanie weenies.

“When I first met Jasmine, she was very interesting to speak to with her wonderful British accent. She was such an elegant lady,” Donaho said. “They shared the idea of a children’s museum with us, and I was named president of the board.”

The idea took off. In the years to follow, the board of the museum would acquire a little old building that was used to repair big oilfield vehicles. For four and a half years, the board — under the direction of the Morans — worked to bring the dream of a children’s museum to life.

“She was involved from the very beginning, and she didn’t want the museum named after her,” Donaho said. “But she is so hard working. That’s what I love about her and her family. Yes, they are people of means, but they visited different parts of the world with their children so they could learn about all walks of life and learn about other cultures. She is a woman of resolve and a very strong advocate for children and animal rights.”

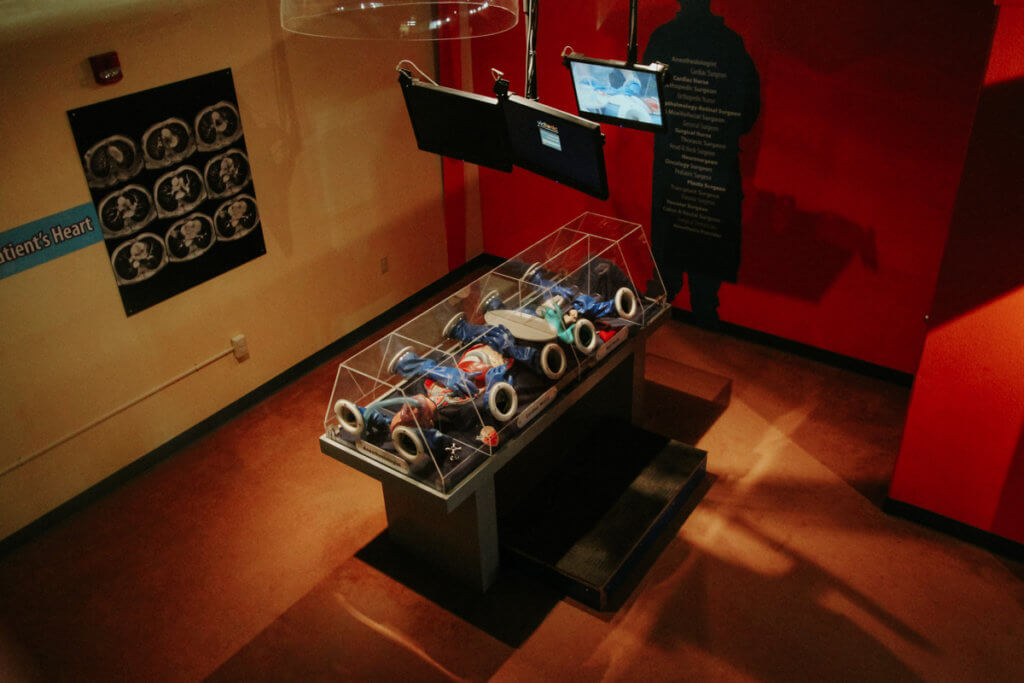

In 1993, The Jasmine Moran Children’s Museum opened, one of only a handful of youth museums in the nation. In the years to follow, the museum would grow and expand, adding exhibits like the climbing maze, the Small Train and Jasmine’s Ark, a Castle Maze, the Kim Henry Science Works Wing, an organ-and-tissue-donation exhibit, and the famous Acrocanthosaurus dinosaur cast that looms in the lobby.

The land surrounding the museum grew as well. Each time an adjoining property went up for sale, the museum foundation purchased it for continued growth.

“Since we opened on January 23, 1993, we’ve expanded nine times,” Melvin said. “Of the 300 children’s museums in the nation, we are in the top five in size with 42,000 square feet and 10 acres of outdoor exhibits. We have a 109-member board and an executive board of 15.”

Donaho, the reluctant attendee of the original meeting, still serves as executive director.

Jasmine Moran: A life well-lived

Jasmine lacks her formerly spry health these days. Years of dance and scoliosis have caught up to her, but her mind, humor, kindness and passion remain the same. As she entered the museum for an interview Nov. 1, her face was only slightly bruised from a bad fall she had suffered while recovering from heart surgery.

“There was this little grasshopper trapped in the house,” she said. “It was getting to be the end of grasshopper season, and I thought it would have a better chance of survival if I took it outside. I fell and banged up my face. Next time, the grasshopper can find his own way out.”

Jasmine has always had a passion for animals and a disdain for animal cruelty.

“Animals are living things, and they feel,” she said. “I despise cruelty. You have to be strong and stand up against cruelty to any living thing.”

Almost single-handedly, Jasmine funded and created the Seminole Animal Shelter and Seminole Humane Society, which adopts out 75 animals a month. She was an avid opponent of cockfighting and has taken powerful people to court over animal rights.

Now, with 11 major surgeries behind her, she has no plans to quit.

“We are all like diamonds,” she said. “A cut diamond has many facets. You can see the beauty on the surface, but underneath all those layers may be something not so pretty. I’ve always made it a point to leave kindness behind. You pick yourself up, and you keep on going.”

Like the true faerie people of the old country, Jasmine continues to do just that.

(Editor’s note: The Oklahoma Heritage Association will publish Jasmine Moran’s autobiography, The Path I Chose, by the end of this year or early 2018.)

(Update: This story was updated at 12:50 p.m., Wednesday, Nov. 29, to correct the spelling of Marci Donaho’s name and adjust a reference to the fortune teller mentioned above.)