By Jennifer Gollan

Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting

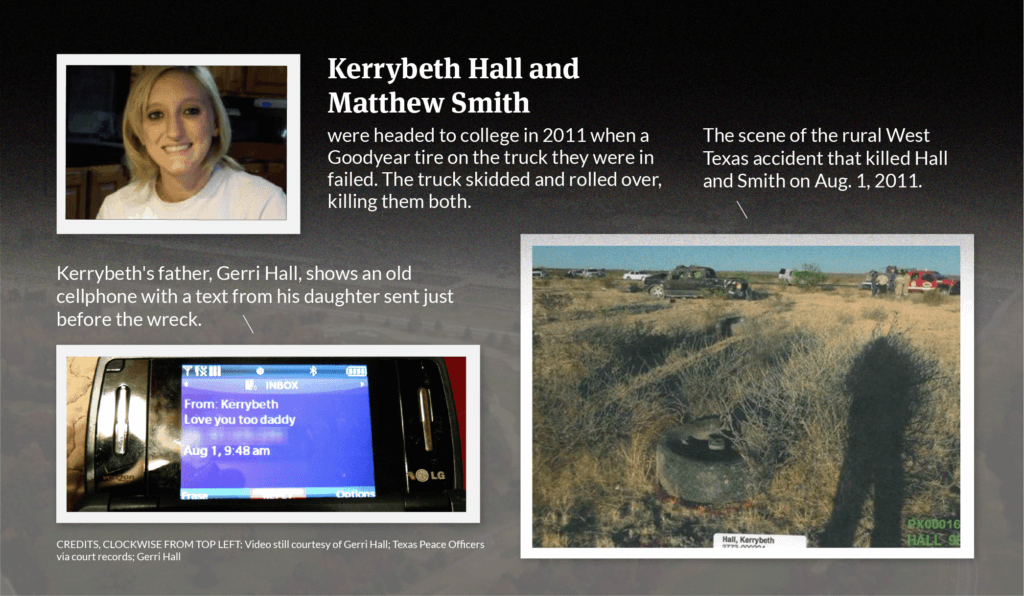

As daylight faded, Matthew Smith and Kerrybeth Hall were in rural West Texas headed to college when the left rear tire of Smith’s black Ford pickup failed.

The truck skidded sideways on the busy highway, smashing through a wire fence before rolling over in the parched plains, killing them both.

Police listed the Goodyear Wrangler SilentArmor tire – among more than 40,000 the company later recalled – as a cause of the crash that August day in 2011.

The fatal accident is a stark example of the deadly consequences of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.’s lax approach to safety, contributing to deaths of motorists on the road and workers in its plants, a six-month investigation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting has found. Tires involved in the accidents were manufactured in Goodyear plants in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and Danville, Virginia, where intense production demands and leaks in the roof during storms have endangered both workers and consumers for years.

RELATED

Goodyear statement: ‘We fell short’ on safety at plants by Jennifer Gollan

Reveal interviewed dozens of current and former Goodyear workers and analyzed hundreds of federal and state agency documents and court records from seven states. In interviews, several former employees said they felt pressure to put production before workplace safety. Others recalled a quota-driven motto invoked on the shop floor: “Round and black and out the back.”

“The pressure to get the job done was very intense,” said Joel Burdette, who worked as an area manager at the company’s Union City, Tennessee, plant before it closed in 2011. Burdette then took a similar job at the Danville plant, leaving in 2014.

“That was a motto: Anything goes as long as it goes onto the truck and gets shipped out,” he said.

About seven months after Smith and Hall were killed, Goodyear sent out recall notices.

“Use of these tires in severe conditions could result in partial tread separation which could lead to vehicle damage or a motor vehicle crash,” the company stated in a letter to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Goodyear noted it had been monitoring problems with the SilentArmor tires since at least May 2010, 15 months before the deaths of Smith and Hall.

The tire in Smith and Hall’s crash was made in Fayetteville, but at least two others died in accidents over the last five years after tires made at Goodyear’s Danville plant failed. Another motorist, Harry Patel of Michigan, became a partial quadriplegic in 2012 when a tire on his Nissan Pathfinder separated, causing the SUV to flip and land in a ditch. That tire was made at Goodyear’s Fayetteville plant.

After hearing arguments from Patel’s lawyers that Goodyear had ramped up production, compromising the quality of its tires, a jury awarded him $16 million, one of the largest product liability awards in Michigan’s history. The 2015 award, which Goodyear has appealed, was cut nearly in half because of state liability caps.

“The shocking collapse of safety controls at Goodyear’s plants has inflicted immeasurable losses on the many families of Goodyear customers killed in avoidable tragedies,” said John Gsanger, an attorney for the families of Patel and Hall.

A deadly record

Manufacturing tires is a hazardous process requiring a vigilant approach to safety. In plants that can stretch over 50 football fields, workers use massive machines to fashion rubber and steel into tens of thousands of tires for everyday motorists and clients ranging from NASCAR to FedEx.

The plants can be grimy. Machines that grind rubber spew fine dust over workers’ clothes and faces. Even after showering, they ooze black residue from their pores, leaving imprints of their bodies on their bedsheets.

“It’s like working in a coal mine,” said Bo Rosas, a former maintenance manager at Goodyear’s Danville plant. “When you blow your nose, you see black film.”

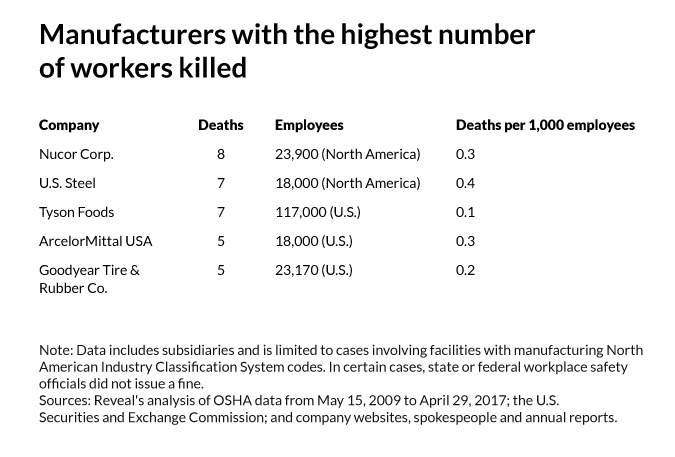

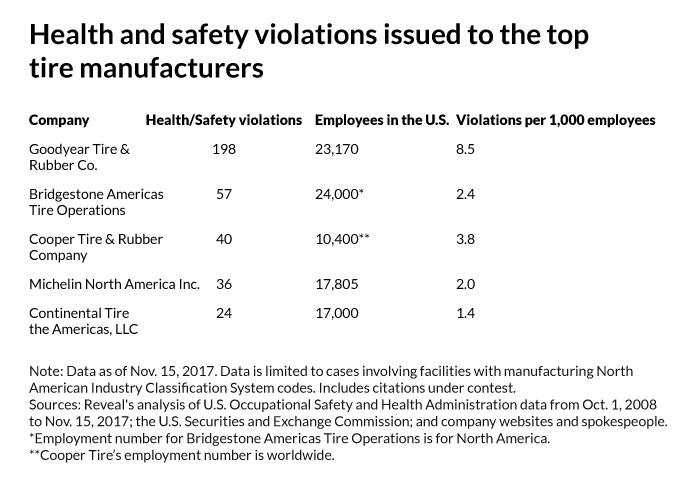

But even among its peers, Goodyear stands out. The tire giant is among the deadliest manufacturers in the nation for workers, Reveal’s analysis of data from the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration shows. Since August 2015, five Goodyear workers have been killed – four at the Virginia plant in one year alone.

Ellis Jones, Goodyear’s senior director of global environmental health, safety and sustainability, called the company’s workplace deaths “an unusual situation.”

“We reacted after every incident,” he said, referring to the company’s rash of workplace accidents. “We did have to take a step back and say, ‘Let’s look at the system within Danville and identify the gaps in the system, and let’s close those gaps.’ ”

While acknowledging those safety lapses, Jones said the company’s tires are safe for consumers.

“Each stage of the process, that raw material, that component is tested, and that finished tire is tested for quality,” he said. “So we’re very confident about the quality of our product.”

After serious workplace accidents, the company’s managers have both clashed with investigators and admitted to regulators that they ignored workplace safety lapses, Reveal found. In one instance, a manager admitted to an accumulation of oil over a period of days due to a reduction in personnel in the cleaning crew.

Since October 2008, Goodyear has been fined more than $1.9 million for nearly 200 health and workplace safety violations, far more than its four major competitors combined.

But its deadly track record has received scant national attention, and the publicly traded company has continued to profit from clients ranging from Boeing to the U.S. military and took in $1.3 billion in net income last year.

Shifting politics in Washington stand to further insulate companies such as Goodyear from accountability. Reinvigorating manufacturing and job growth is at the core of President Donald Trump’s economic agenda.

Yet protections for factory workers, who overwhelmingly supported Trump, are being dismantled. The administration is rolling back and postponing Obama-era protections in keeping with goals laid out by the National Association of Manufacturers, a prominent Washington industry group.

Richard Kramer, Goodyear’s chairman, chief executive officer and president, serves on the association’s board. A Goodyear spokeswoman said Kramer was unavailable for an interview but made Jones available instead.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass. – a member of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions – said lobbyists for dangerous companies should not be permitted to dismantle workplace protections.

“President Trump and Republicans in Congress have taken one whack after another at regulations that make sure workers are safe on the job,” Warren said in a statement to Reveal. “Washington is supposed to work for hardworking Americans, not for the trade associations for the companies that make their profit by taking shortcuts on worker safety.”

In the pit

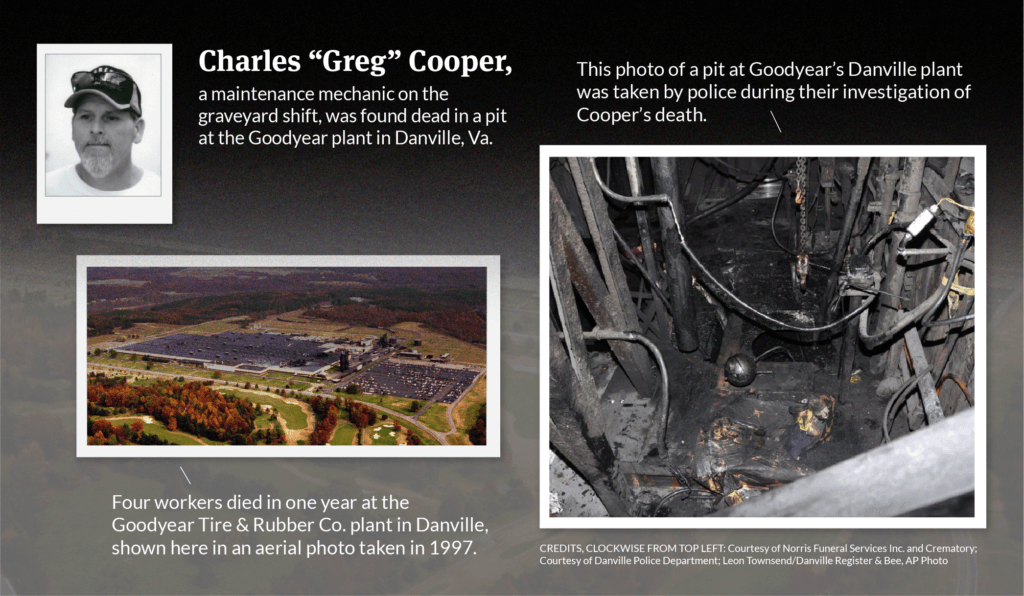

Just before midnight on April 11, 2016, Charles “Greg” Cooper, a maintenance mechanic on the graveyard shift, descended alone into a machine pit in the dimly lit basement of the tire plant in Danville.

He set to work replacing a broken rope that wicked oil from wastewater swirling in a huge vat. Rubber, hooks and wires lay strewn around him on the floor near the pit, where steam rose from the boiling water.

Federal rules require a safety guard or cover on any openings in the floor. But about six months earlier, an electric pump had broken, and “there was still a huge hole left directly over the pit,” records show.

Several hours passed before a manager noticed that Cooper was gone and dispatched his co-workers to search the plant. Finally, one of their flashlights sliced through the darkness, its beam illuminating his body, floating face down in the pit. Then came the official call: “Man down!”

It was far too late. Cooper had been boiled alive.

Cooper was the third of four workers to die at the company’s Danville plant over one year ending in August 2016.

A Virginia workplace safety investigator who arrived to scour the area where the 52-year-old died noted it was slippery. The floor around the gaping hole atop the pit was “covered with oil, grease, water and rubber due to lack of housekeeping and it simulated a condition like working on ice,” the investigator wrote.

The hole had been in plain view of a maintenance manager who was required to inspect the area on each shift, records show. Investigators found two other holes nearby.

After the accident, Greg Kerr, the plant’s manufacturing director, told a local newspaper that Goodyear would “work with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the local authorities to fully investigate the incident.”

Yet Goodyear’s conduct after the investigation proved quite the opposite.

“Employer difficult to deal with,” an investigator from the Virginia Occupational Safety and Health Program noted. “Slow to respond to any request, encouraging employees to not cooperate.”

Some Goodyear workers told local police, on condition of anonymity, that Cooper never should have been working alone that night. They said the plant’s policy had required maintenance employees in the area to work in pairs since 2007, when a worker in the same part of the plant was severely burned and later died.

“At no time were maintenance workers to work in that area alone, as it is one of the most dangerous areas of the plant,” police investigators wrote. Nevertheless, Cooper was assigned to make the repair by himself, police records show.

In near darkness, giant machines resembling egg beaters thrash bales of rubber into flat sheets, drowning out workers’ voices. So even if Cooper had screamed for help, “there’s no way you could get in touch,” Wayne Barber, his longtime work partner and close friend, told Reveal.

“What gets me is him being in the pit for so long and nobody going to look for him,” he said. “The supervisor should have found out where he was after that long.”

Barber wrestles with how things might have been different if he had been at Cooper’s side that night instead of at home mourning the recent death of his wife.

“He wouldn’t have stayed in that hole for four or five hours,” Barber said as he sat on his front stoop, adding quietly, “It could have been me. We might have both ended up in the hole.”

Chronic workplace safety hazards

While investigating an earlier incident at another Goodyear plant, federal workplace safety investigators found unguarded floor holes had long been a problem.

In February 2015, about a year before Cooper was killed, a worker at the Topeka, Kansas, plant suffered third-degree burns on the left side of his body as he worked on a tire-curing press.

Investigators wrote that the plant’s then–safety manager, Tim Washeck,told them that floor holes had been “observed for as long as they can recall and … covering them had not been considered in the past.” OSHA cited the plant for the violation.

The following month, a worker at the company’s plant in Gadsden, Alabama, fell from a platform, which lacked standard railings, onto a conveyor belt, breaking his left arm, shoulder, four ribs and collarbone. Oil leaking from a nearby milling machine covered the floor where he had been working. The plant’s safety manager, Charles Skaggs, was aware of the oil leak and open-sided platform, investigators noted.

Washeck and Skaggs did not return calls seeking comment. Jones, Goodyear’s senior safety director, declined to comment on specific cases but noted that Goodyear safety officials are expected to ensure that “every associate goes home safe.”

In settlements with the Virginia Occupational Safety and Health Program after lapses that included the four Danville deaths, Goodyear admitted it had violated workplace safety and health laws more than 100 times. The company agreed to a reduced fine of $1.75 million earlier this year.

And in a move that three former top federal safety officials called “highly unusual” and “outrageous,” Virginia regulators at the time invited the company to apply for the state’s so-called Voluntary Protection Program, which shields companies with exemplary safety programs and below-average injury rates from routine safety inspections.

Virginia is one of 28 states and U.S. territories that run their own workplace health and safety programs, covering private- or public-sector workers or both. Most of these states have adopted standards that are identical to those set by OSHA.

Soon after the Goodyear settlement, a 61-year-old contract worker was killed at the company’s Topeka, Kansas, plant when a falling object struck him in the head. He left behind a wife and daughter.

OSHA imposed a fine of $27,713 against Goodyear for the accident, which the company quickly contested.

“A firm in which five workers are killed over 18 months is clearly a firm in which the management is not adequately focused on worker safety,” said David Michaels, who led OSHA under President Barack Obama and now is a professor at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health.

“It is also a sign of the absence of operational excellence, since worker fatalities and serious injuries do not occur when the production process is tightly controlled.”

‘Round and black and out the back’

Gerri Hall remembers the day his daughter, Kerrybeth, came home from school and told him she’d decided to become a paramedic. She was 14. The petite blonde with a piercing laugh learned that her father, a firefighter and EMT, had rescued her friend after a car accident.

“She thought that’s what she was here for, is to help people,” Hall said.

Two weeks before she was due to start a paramedic program at Victoria College in Texas, police found the 18-year-old’s mangled body still strapped into the passenger seat after the Goodyear tire failed.

“Disbelief,” said Hall, 51, who lives in Placedo, near the Texas Gulf Coast, a little more than an hour’s drive northeast of Corpus Christi. “I always wake up thinking I’ll see her.

“Kerrybeth was our rock, and we all leaned on her,” Hall added. “It has torn the foundation of our family apart.”

Since Kerrybeth’s death, Gerri Hall says he has suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. He quit his job as an EMT and firefighter, unable to face any more car accidents without picturing his daughter. In a safe at home, he keeps an old cellphone with a text his daughter sent him just before the wreck. “Love you too daddy,” she wrote.

A tire industry expert hired by John Gsanger, the Hall family’s lawyer, blamed design and manufacturing flaws for weakening the Goodyear tire before it failed, according to court records. Goodyear’s lawyers insisted the tires were safe and said the truck must have hit an object that caused the tire to separate.

A dozen former workers at the company’s Fayetteville and Danville plants gave sworn statements criticizing the plant’s practices, according to court filings. In interviews with Reveal, more than seven other former Goodyear workers blamed intense production demands and leaks in the plants’ roof during rainstorms for weakening some tires, potentially causing them to fail. In court records, some former workers have said managers expected them to meet production quotas, but it is unclear whether quotas still exist at Goodyear.

In a sworn statement, David Hyde, who worked as a tire builder at the Danville plant from 1977 to 2009, said the “round and black and out the back” motto was emblematic of the company’s operational failures.

“Goodyear talks the talk, but they don’t walk the (walk),” Hyde said. “They, you know, they say they want to build a quality product. … You just don’t understand the stuff I’ve seen out there. It’s not good.”

Jones, Goodyear’s senior safety director, acknowledged that some workers use that motto but said workers concerned about unsafe conditions are encouraged to speak up.

“I’ve worked in Danville, worked in many factories, so you hear that, but again, every worker has the right to stop the process,” he said.

Pressure to keep up production was intense, however, according to James Goggins, who worked at the Danville plant for more than 20 years before retiring in 2014.

Officials from Goodyear’s headquarters in Akron, Ohio, “would call down to Danville all the time, and all they would do is check the numbers,” Goggins said. “They were more interested in making the production numbers.”

Goggins and other former Goodyear workers in Danville recalled how water leaked through the roof and gushed through manholes when it rained. Workers are trained to avoid moisture in the production process because it can prompt tire treads to separate, causing a blowout.

“You can look down and see that water is shooting up from the floor like fire hydrants and flooding the department,” Goggins said.

When it rained, workers said they would call maintenance crews to drape tarps over the equipment, draining the water into dumpsters.

“If there is a roof leak in a facility – and I’m not going to say we don’t have roof leaks in a facility – that local management team will put a process in place to fix the roof leak,” Jones said. “There are also processes in place, safety systems in place, to make sure people are not in a hazardous situation.”

That claim means nothing to Gerri Hall, who visits his daughter’s grave every Sunday morning.

“Goodyear doesn’t care about life. They just want to make that money and let their CEOs get their big bonuses. Let’s just throw out as many tires as we can.”