STILLWATER — It’s barely 6:30 p.m. when a sobbing woman runs in cradling a small, dark-furred scruff of a dog.

No words are spoken, but a wave of frenetic energy floods the room. A team of four people in white coats carefully lays the dog on a steel table, hunching over as their hands wave and work like magicians casting a spell. The dog lies quietly and motionless.

The frantic action doesn’t last long. The energy slows, and one of the veterinarians peels away to fetch a sunshine-yellow towel. Gently, with tender hands, the dog is lifted up briefly and then wrapped softly and carefully into the cloth, its little face hidden.

The pet was deceased before it even arrived, but the veterinarians still did all they could. Like any other emergency room, sometimes patients don’t survive.

But at the Boren Veterinary Medical Hospital at Oklahoma State University, miracles happen every day for the lives of pets and other animals. Dogs that were thrown off bridges with shattered hips walk away to join new families. Calves with digestive problems are treated with the help of the hospital’s donor cow to live healthy lives. A tortoise gets a new 3-D-printed breast plate to replace a damaged one. Surgeries become life-saving success stories.

At the heart of it all are students and graduates who not only earn hands-on experience in treating animals of all sizes, but who also give pet owners and the public a chance to save their furry friends.

And, like any other hospital, every night in the ER is an adventure.

Serving the Community

The OSU-VMH provides emergency service to the general public in the surrounding Stillwater area as well as for local and regional referring veterinarians and their clients. Emergencies are accepted any time, even on holidays.

OSU’s Boren Veterinary Medical Hospital is named after former Oklahoma Gov. David Boren, the current president at the University of Oklahoma. The hospital treats patients, but its primary goal is to teach veterinary students as well. Students and graduates serve on staff at the hospital, which is staffed 24 hours a day with registered veterinary technicians and a veterinarian is on call for emergencies at all times.

In addition, the Veterinary Medical Hospital has board certified radiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, internists and ophthalmologists who help critical care patients.

Every day, the hospital provides 24-hour care for large animals like horses and cattle, small ruminants like goats, small animals like dogs, cats and exotics, camelids and more.

‘Birds, rats, everything’

One night in January, a jovial little wallaby hopped about the treatment room, nibbling treats as it recovered from an illness.

Vanessa Snyder, Sarah Schock and Ian Konsker, all DVM and interns of small animal medicine and Surgery, worked the floor at the ER that night, checking on animals who were recovering and dealing with the occasional panicked visitor. Joao Brandoa, LMV, MS, is a clinical assistant professor in zoological medicine and the resident expert for avian, exotic and zoo animal medicine. Brandoa was the wallaby’s chief doctor, and he cooed at the animal with his Portuguese accent, cradling it in his arms for visits.

“We treat patients, but also our primary goal is to teach students to become veterinarians,” Schock said. “We have the vet students, but I also just graduated the school, and now I’m doing an internship with the goal of pursuing a specialty. I want to do surgery, and in order to do that, you have to do a residency. I’m in training for that right now.”

On the small-animal side of the hospital, dogs and cats are the usual patients, but the vets will treat nearly any small animal that comes in.

“Birds, rats, everything,” said Konsker. “Large animal consists of food-animal things — pigs, cows, goats, sheep, llamas, alpacas, camels. I have a zoo background. I was a veterinary assistant at the Nashville Zoo for a time, so I have worked with camels before. That’s my goal — to get back to zoo medicine.”

Like any emergency room at night, injuries that need treatment are as varied as the patients that come in. Much like the dog that didn’t make it, sometimes owners come home from working all day to find their pet sick or dying. Others suffer lacerations or attacks from other animals. In the big-animal side of the hospital, problems tend to revolve around prolonged labor that requires a C-section or similar actions.

“There is definitely an emotional toll. When it comes to euthanasia, it’s different from dead on arrival,” Konsker said. “When it’s a euthanasia case, usually it is because an animal is suffering, or if it’s not suffering at that moment, then it has something that will cause it to suffer that can’t be fixed. So it’s the owner’s decision about the timeline and when it’s right. There is no correct answer on when the right time to euthanize an animal is, but it’s the assurance that the animal is no longer in pain. It can be difficult for people.”

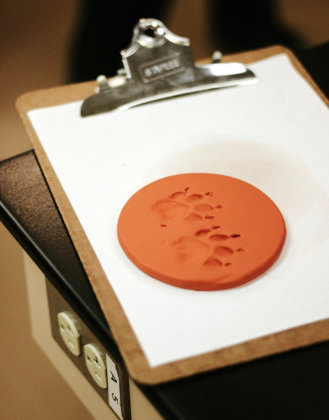

The Emergency Room at the OSU VMH has a standing policy that, whenever a pet dies, vets write a condolence letter and create a clay paw — a paw print from the pet commemorated in clay — for the owner to take home.

“I’ve seen weird toxicity cases,” said Schock. “I saw one case where the dog ate bread dough and it expanded in the stomach, and it became drunk almost from the bread fermenting in the stomach.”

Synder and veterinary technician Holley Ladymon said dogs especially can ingest deadly substances, and those cases are a challenge to treat.

“Last year, we had three dogs that drank gasoline, and (another organization) didn’t know what to do for that,” Ladymon said. “They drank a lot.”

Another dog had been hit by a car, splitting its diaphragm muscle so severely that its intestines went into the chest and its back was broken. The owners, faced with a financial choice, were able to afford the surgery to repair the diaphragm, but not the back.

“We made a little back cast for him. They kept him in a cage for eight weeks, and the dog is doing great,” Schock said.

Konsker, with his love of exotics, worked on a coatimundi, a little ring-tailed South American animal that resembles a raccoon, but he said it was one of his saddest experiences. The coatimundi had escaped from a house fire only to be attacked by a pack of dogs when it got outside.

“We get interesting phone calls, too,” he said. “My favorite is one morning at about 10 a.m., an owner called to ask if his cockatoo could drink his morning coffee with him. We highly recommended he not do that.”

3-D printer helps tortoise mate

In many ways, the Oklahoma State University’s Boren Veterinary Medical Hospital is more state-of-the-art than many human hospitals. The future is bringing technology that’s even more sophisticated, said Bruce Williamson, MBA, hospital administrator

“Every day is a new day to me, and it’s amazing to see. One of the things I like to say is that we watch miracles every day,” Williamson said. “We had a tortoise in here — a high-valued tortoise. He had to have a surgery, so they had to take off his chest plate. He’s breeding stock, so the problem he had was he couldn’t mount to do his job because the female shell would injure him.

“So we are working on things like 3-D printers that allowed us to print a new chest plate to put back on. There are things like that happening here every day. It blows me away what we do here.”

The hospital is also in the process of swapping out a four-slice CT scanner for a 64-slice CT scanner.

“That will step up our capabilities for diagnostics quite a bit,” Williamson said.

Built in 1983, the hospital is constantly expanding and growing. New technology is introduced yearly, including a new app which allows vets to send pictures of animals being treated to their worried owners, which, from a business perspective, helps cut down on phone calls.

The Boren Veterinary Medical Hospital also keeps “donor” animals on site that can give blood when transfusions are needed. Williamson said those animals are usually the most pampered animals he’s ever seen.

“They are given walks, have their teeth brushed twice a day and cared for 24/7,” he said. “They are given wellness exams, and, after a year or two of service, we adopt them out. Our students learn how to care and handle these animals. In our large-animal side, some students have never been around a cow or a horse before, so it’s important for them to know how to handle these animals.”

On the large animal side, a friendly cow named Daisy has a surgically-inserted port in her side. Vets are able to remove digestive fluid from her stomach painlessly to help treat calves whose stomachs aren’t working properly. In another area, stalls are padded for horses that come out of surgery, minimizing the risk of additional injury if they panic.

The hospital’s provision of such diverse care means resources, personnel and a major financial investment is required. From dentistry to cardiology, the hospital includes diagnostic imaging, internal medicine, the Kirkpatrick Foundation Small Animal Critical Care Unit, ophthalmology and surgery.

Challenges in meeting the goal of providing medical care exist as well. State budget cuts to higher education have taken their toll, Williamson said. At the overnight clinic, volunteers bring coffee which is no longer in the hospital budget. But a desperate need for veterinary technicians is one of the top concerns.

“Nationally, there is a shortage of registered veterinary technicians right now,” Williamson said. “We’ve increased our number of techs on shifts to 10, but the problem is, we can’t get applicants. We’ve been staffed with five. We are trying to find creative ways to get vet techs. We need them bad.”

Some studies, Williamson said, suggest the average career span of a veterinary technician is five years before they burn out. He said they also have an alarming suicide rate.

“The stresses are high. You see the shifts they are working. You can’t blame them for not wanting to stay,” he said.

However, until a solution is found, the Boren Veterinary Medical Hospital will continue to “make miracles happen every day.”

“It’s amazing to see what goes on here,” Williamson said. “The level of care here, the new technology and what our staff does daily just blows me away every single day.”

More photos from the OSU Veterinary Medical Hospital

(Correction: This story was updated at 11:05 a.m. Tuesday, Feb. 20, to attribute a quote from Holley Ladymon correctly. Also, Ian Konsker formerly worked at the Nashville Zoo. NonDoc regrets the errors.)