Oklahoma lawmakers achieved a major bipartisan feat last week with 75 percent of House and Senate members voting to pass more than $400 million in new taxes that will increase education funding and teacher pay. Combined with a cap on income tax deductions in HB 1011XX, the historic votes will inject about $500 million in new revenue into a state government that has primarily seen cuts over the past 10 years.

With educators still seeking more classroom funding, health entities seeking provider-rate restoration and other state agencies trying to climb back to pre-recession service levels, legislators and state officials will seek additional revenue sources in the coming years.

This past week’s tax hikes raised Oklahoma’s cigarette tax by $1, gas and diesel taxes by $0.03 and $0.06 respectively. Lawmakers also raised the gross production tax incentive rate on oil and gas wells from 2 to 5 percent. The GPT hike came after two years of intense argument among Democrats and Republicans, and it occurred in the face of oil and gas leaders fighting against the substantial rate hike.

But with those three tax areas likely off the table for subsequent-year investments in state services, where might Oklahoma find additional revenue moving forward?

One answer that may prove as controversial and contentious as GPT could be a two-word term unfamiliar to most Oklahomans: exclusivity fees.

Exclusivity fees: Part of potential 2020 compact negotiations

Exclusivity fees are paid by Native American tribes to the state for exclusive rights — granted by compact — for the operation of Class III gambling. Negotiated in 2004, Oklahoma’s model tribal gaming compact currently sets exclusivity fees at 4 percent for a tribe’s first $10 million of adjusted gross revenues, 5 percent for the next $10 million and 6 percent beyond that on gambling revenue earned by casinos in Oklahoma. (There is also a 10 percent rate on the monthly net win of prize pools for nonhouse-banked card games.)

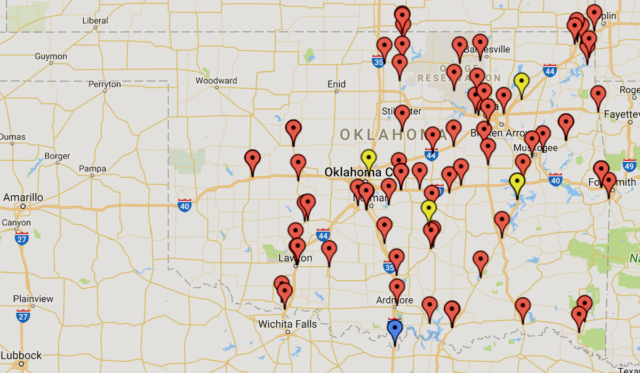

While Oklahoma has the nation’s largest number of tribal casinos, the state’s exclusivity fees — $132 million in Fiscal Year 2016 — are seen by some as being too low considering how tribes are making more than $2 billion annually from Class III gaming.

As a result, some state leaders are hoping to increase the exclusivity fee percentages when Oklahoma’s tribal gaming compacts are up for potential renegotiation in 2020. Both the state and tribes would need to agree to reopen the compacts, and they would have a limited timeframe in which to do so. But if they do, exclusivity fees could be a major part of negotiations.

Those fees are dedicated to specific areas of state government, with the largest chunk going toward education.

From The Oklahoman’s Randy Ellis in 2016:

The Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services receives $250,000 each year from the exclusivity fees. The Education Reform Revolving Fund (1017 Fund) receives 88 percent of the remainder, and the state’s General Revenue Fund receives 12 percent. This past fiscal year, the education fund received nearly $116 million, while about $16 million went into the General Revenue Fund, where it can be appropriated by the Oklahoma Legislature.

Balls in the air while dice are rolled

Some of the primary leverage Oklahoma’s next governor might have in gaming compact negotiations could come from the introduction of “ball and dice” table games, which are currently prohibited in Oklahoma but sought by tribes.

HB 1013XX was passed by the House last week as part of budget negotiations. Estimated to bring in an additional $24.9 million under current exclusivity fee levels, the bill has not been heard in the Senate, where lawmakers have expressed a hesitancy to greenlight ball and dice without renegotiating the compacts.

While tribes have advocated for the ball and dice expansion last year and this year ahead of 2020 window, some state leaders hope to retain ball and dice games as a bargaining chip to raise the 4 percent, 5 percent and 6 percent thresholds for exclusivity fees. Other gaming-heavy states across the country are already collecting revenue at higher percentages.

In Connecticut, state coffers receive 25 percent of slot-machine revenues, roughly five times as high a percentage as Oklahoma. In New York, an expansion of tribal gaming in 2013 included between 37 and 45 percent tax rates on slot machine revenue and 10 percent for table games.

However, Oklahoma and the tribes operating casinos within state boundaries benefit from a relative lack of competition in surrounding states. Texas has only one tribal casino, located in Eagle Pass on the Mexican border. Arkansas has only two casinos, both located in racetracks and not owned by tribes. Kansas has only four gaming compacts with tribes, and the state collects no taxation from the tribal casinos themselves except what is deemed necessary for regulation.

Would picking a fight over tribal gaming exclusivity fees open the door for surrounding states to increase casino authorizations? Perhaps.

But in the coming years as Oklahoma seeks to find new state revenue from existing sources, raising exclusivity fees will almost certainly be seen as a lucrative option for a state featuring more than 120 tribal casinos.

With lawmakers having tapped into Oklahoma populism to squeeze more revenue out of GPT, exclusivity fees could be a subsequent public-perception battle on the state’s horizon.