On the topic of Medicaid expansion, Oklahoma health care advocates have ridden an emotional roller coaster for the past two weeks.

Asked by media, Republican legislative leaders have indicated a willingness to pursue some version of a coverage-expansion plan that hospital CEOs, chambers of commerce and leading Democrats have desired for years. During a Jan. 30 Associated Press forum, new Gov. Kevin Stitt even answered affirmatively when asked if he was open to pursuing the $9-to-$1 federal-to-state match that would fund health coverage for low-income adults.

Days later, fellow influential Tulsan George Kaiser published a Feb. 3 commentary in the Tulsa World urging state leaders to pursue Medicaid expansion, though he stopped short of using Stitt’s name in print. Once again, health care advocates were happy with hope.

The very next day, however, Stitt delivered his State of the State address and dialed back the morphine drip:

While Medicaid expansion currently stops at a 90 percent federal match, we cannot assume that it will remain this high forever. The estimated $150 million price tag today for Oklahoma to expand Medicaid could leave us down the road fronting more than $1 billion when the federal government pulls back on its commitment. They’ve done it before and they will do it again.

Medicaid is the fastest growing expense in our state budget, and before we commit our state to accepting even more Medicaid dollars, Oklahomans deserve accountability and transparency with our state’s management of the Healthcare Authority.

Oklahoma is the only state in the nation where the governor does not have the authority to provide oversight of this agency. We are sticking out like a sore thumb, and this must change.

Rural Republicans recognizing the problem

Unpacking the political positioning of a new governor in his second major speech can be tricky business.

Did Stitt believe the hospital cart was getting ahead of the nurse on Medicaid expansion? Did he want to delay picking a political fight with right-wing advocacy organizations that adamantly oppose expanding public health insurance programs? Was he providing cover for a GOP-led Legislature facing its own internal battle on the issue?

While the answer to all three questions could be yes, two factors are certainly pushing Republicans toward considering some sort of Medicaid expansion proposal.

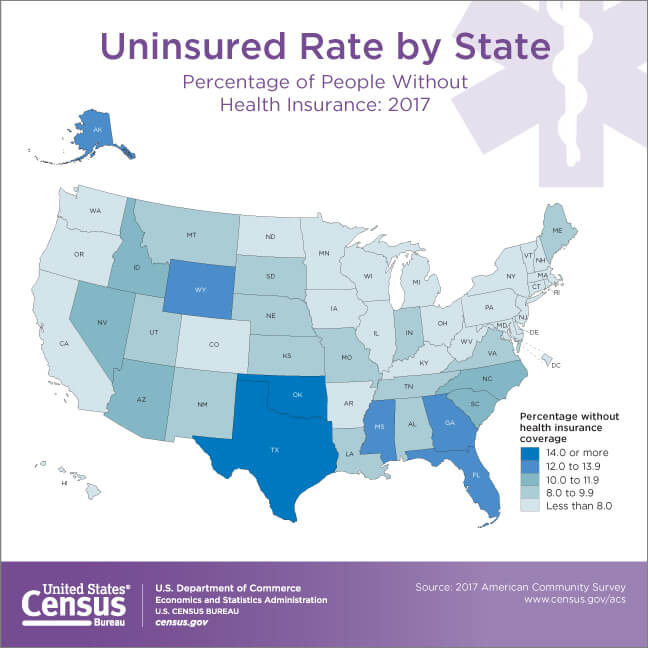

First, Oklahoma hospitals continue to see some of the nation’s highest uninsured rates throughout the communities they serve. That resultant fiscal strain takes a greater toll on rural hospitals, as evidenced by a rash of closures in Wilburton, Eufaula, Frederick, Sayre and elsewhere.

“Health care needs for rural Oklahoma are very much different than the needs in the urban centers,” House Speaker Charles McCall (R-Atoka) said at the AP forum when asked about Medicaid expansion.

Much of McCall’s House GOP caucus represents rural Oklahoma, and conversations about Medicaid expansion have percolated among young Republican lawmakers in both chambers.

For example, Sen. Greg McCortney (R-Ada) has filed SB 605, which would direct the state’s Medicaid agency to “establish the Oklahoma Plan” as a Medicaid expansion alternative providing premium assistance within Insure Oklahoma. The four-page bill has been assigned to the Senate Retirement and Insurance Committee.

2018 state questions taught lessons

Second, word spread at the end of 2018 that progressive Oklahoma leaders — such as Kaiser — will be mounting a Medicaid expansion ballot initiative for the state’s 2020 election. In 2018, Idaho, Nebraska and Utah each passed a Medicaid expansion ballot initiative, giving Oklahoma Democrats and Republicans ample evidence that a similar state question would have momentum here.

To that end, the words “state question” have grabbed the attention of Republican leaders, as a pair of 2018 ballot initiative efforts taught two different political lessons for lawmakers and advocacy groups.

As the Legislature struggled to pass a bipartisan revenue package for teacher pay and other budgetary needs last year, a filed ballot initiative quickly shaped debate over oil and gas gross production tax rates. The ballot initiative’s threat of 7 percent GPT ultimately fractured oil and gas industry advocates and reminded onlookers just how effectively a looming state question can drive compromise in the Legislature. (Those pushing the 7 percent ballot measure backed off when lawmakers eventually raised the GPT incentive rate to 5 percent.)

Similarly, last year’s most prominent ballot initiative taught another lesson, should legislators listen. Passing with 57 percent voter approval, State Question 788 legalized medical marijuana and created an imperfect framework that the Legislature now must tweak without overturning the will of the people. Some Republican lawmakers spent the 2018 legislative session trying to pass a more robust medical marijuana framework ahead of SQ 788’s ballot appearance, but other GOP leaders believed the state question could be defeated owing to fear of the proposal’s language as drafted.

In retrospect, some Republicans now wish they had rolled their own medical marijuana guidelines before SQ 788 was passed to them. Likewise, some of those same Republicans believe action should be taken ahead of any 2020 state question on Medicaid expansion.

Kaiser concluded his commentary appealing to lawmakers with exactly that message.

“The people would vote for it — as they did by big margins in Utah, Nebraska and Idaho — but it shouldn’t be necessary to do that if our representatives addressed the problem in the normal deliberative legislative process,” Kaiser wrote. “I sense tremendous private sympathy to resolve the issue among the majority of senators and representatives. Legislation usually generates better results than last resort referendums.”

Just how “private” GOP sympathy for Medicaid expansion will stay this session remains to be seen, but lawmakers have plenty of reason to push for a compromise and have conservative blueprints for financial implementation from states like Arizona, Indiana and Virginia.

Still, with the 2020 electoral cycle more than a year away, Republicans will have plenty of time to disagree with each other about what to do on the topic of Medicaid expansion.