OKEMAH — On a giant concrete platform beneath bright stage lights and a giant picture of the notable protest singer Woody Guthrie, songwriter Jaimee Harris belted out the lyrics to Snow White Knuckles, her story of addiction and recovery set to song.

It was a story she has sung to women in prison and to those in recovery groups from Tulsa to Austin. It’s a story about the injustices of a criminal justice system that often traps those struggling to get out of it.

Saturday, Harris told her story at the Woody Guthrie Folk Music Festival where she participated in a panel discussion about protest music and then sang about it on the outdoor stage to more than 2,000 people who had spread their lawn chairs on the Pastures of Plenty, an open field in Okemah’s eastside industrial park.

For the panel, Harris and other singer-songwriters — John Cooper, Tim Easton, Peggy Johnson and Barry Ollman — sat in wooden chairs beneath the porch awning of a replica of Woody Guthrie’s birthplace home recreated at the Okemah History Center and shared their thoughts about the rhyme and reason of “protest music” in today’s culture. The discussion was titled, “Something to say — Making music that matters.”

The musician has the power

For Harris, her protest is about the criminal justice system, which jailed her for drug and alcohol offense five years ago in her home state of Texas. Probation required her to undergo drug rehabilitation, but her health insurance would not pay because she had been sober for more than 60 days by the time the sentence was issued.

“The state told me at 70 days sober to start drinking again, to reset my sobriety date, so that my insurance would cover my rehab,” Harris said. “I found another way. I just couldn’t do that. I tried to get sober four or five times before, and it never worked out. I had come too far.”

Since, that life experience has caused her to channel important messages through songs that promote criminal justice reform, including in her neighboring state Oklahoma, where more women are incarcerated per capita than in any other state.

“I like writing songs because I feel like my speaking words are not the clearest,” Harris told the panel audience. “Being a songwriter gives me a voice to say something when I may not be able to verbalize it. I realized I can tell my own story.”

Festival organizers believed such a discussion during the currently turbulent political times was appropriate, especially at a gathering which pays homage to Guthrie.

“The musician has the power of the bully pulpit. You’ve got the microphone,” said Ollman, a sing-songwriter and collector of historical items associated with all things Woody Guthrie. He moderated the discussion.

But each of the song-writers refuted the perception that all protest music is negative.

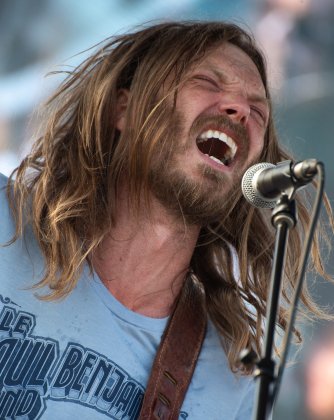

“It’s great to know what you hate. And sing about it and are passionate about it. But, what do you love? What are you for? That’s also important. You’ve got to sing songs about things you are for,” said John Cooper, lead singer of the Red Dirt Rangers.

Cooper said his band’s song, Leave this World a Better Place, is a protest song, but a positive one. At the same time, his band plays “more pointed” protest songs like Red State Blues, a criticism of far-right extremism on the political scene.

The Red Dirt Rangers‘ beginnings in issue activism came while students at Oklahoma State University. Their first song was Neighbors, with the opening line: “I don’t care what the neighbors say….” It was a protest song that reflected Cooper’s desire to resist conformity. The band has more recently created music about chicken farms and processing facilities threatening water quality of the Illinois River in northeastern Oklahoma.

“There never was a time we weren’t writing songs, and it became topical songs very quickly,” Cooper said. “You find over time places that your music fit into causes that you believe in.”

He said protest singers are modern day reporters who bring attention to problems that need to be addressed.

‘All the best protest songs are really love songs’

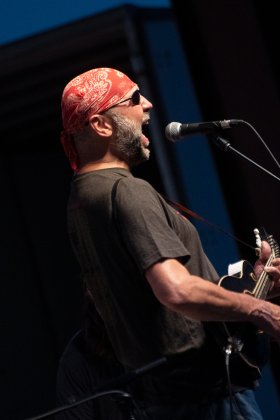

Easton, a frequent artist at WoodyFest, said his issue-advocacy music led to the establishment of a similar festival in Alaska where he works to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge from mining. He said liberal environmentalists have joined conservative hunters and fishermen in protest because of their common love to maintain pristine wildlife habitats. He said his songs hope to bridge seemingly divergent political groups where there is common interest.

“All the best protest songs are really love songs,” Easton said. “You ask (the songwriter), what are you trying to unite people with, instead of divide them?”

RELATED

Peggy Johnson is more than a protest singer by Michael Duncan

Oklahoma City songwriter Peggy Johnson said protest singers have to feature words that are true and that gather people around a common goal.

“Music has a way of doing that,” she said. “Not only do the words need to gather the people, but the spirit of the song needs to gather people.”

But sometimes protest music can be confrontational. Johnson learned that demonstrating support of abortion rights in Wichita, Kansas, where the political debate was heated. That city’s only abortion physician was later murdered. At a rally Johnson and her pro-choice friends, although outnumbered, confronted anti-abortion protesters who were carrying signs of dead fetuses.

She said Mountain Song, a song by feminist songwriter Holly Near, appeared in her head as a means of protection.

“I started singing, and my friends had these petrified looks on their faces as we walked down right into the middle of them and sang this song at the top of our lungs,” Johnson recalled. “The power of music is great. I felt totally safe. I felt like I was in a spiritual bubble. Nobody could touch me.

“I realized I had my back to the guy I was singing to and so I turned around and sang it right in his face. It was the most powerful I’ve ever felt. You can use your music for that kind of power. Not hatred. Not meanness. Just protection.”

Each of the songwriters who participated in the discussion Saturday said the Woody Guthrie Festival experience — which includes meeting and singing with heralded folk singers Joel Rafael and Ellis Paul in the tradition of Guthrie — was instrumental in encouraging them to make important messages in their songs.

“Woody talked about injecting yourself into the bloodstream of the people — so we can be one with our people. As an artist, that’s an endless possibility and opportunity. I always say, what to write about? Well there is no shortage,” Ollman said.

And for Oklahoma artists, there is an added factor.

“Being a musician in Oklahoma, we are kind of lucky because Woody just kind of comes with us,” Cooper said. “He is just part of what we do. We don’t even think about it. He’s just part of the air. As a songwriter here you are kind of blessed that way.”

Photos from WoodyFest 2019