Everyone made mistakes at 18 that they regret. Unfortunately, I have been living with the consequences of mine for the past nine years. In 2011, I made some bad choices that led to three felony convictions and a 20-year prison sentence for simple drug possession and theft. If I had committed these offenses today, they would be misdemeanors under SQ 780, which voters approved to reclassify these low-level offenses from felonies to misdemeanors, and I would not have lost years of my life behind bars.

Originally, I received a 10-year deferred sentence as long as I could pass a drug test. But addiction is a vicious disease and not one I could beat at the time. After I failed a drug test, I went to drug court and agreed to an increased sentence of 20 years in prison that was used to try to scare me to not use drugs. But that’s not how addiction recovery works. I ended up failing drug court and was sent to prison for 20 years – by many standards an extreme sentence for my offenses.

Last December, the Pardon and Parole Board and former Gov. Mary Fallin agreed my sentence was excessive and granted me commutation. Over the past nine months, there have been some really great moments and some very difficult ones as I learned how to navigate life outside prison with felony convictions.

I worked hard in prison to make sure when I was released I could be a better person, a better mom and provide for my family. I received my GED and cosmetology license, participated in courses on parenting and handling the stresses of life without turning to my addiction. I wanted to be able to stand on my own two feet when I was released, but I realized when I got out, I’d be fighting an uphill battle against barriers that restrict me in almost every aspect of my life. My felony record has kept me from being able to secure housing, Cherokee Nation assistance, custody of my children, education and career advancement opportunities, financial assistance and the ability to vote.

One of the biggest hurdles I had to overcome was finding my own home so I could start the process of getting custody of my two daughters back. It took seven and a half months to find an apartment that would accept me due to my felony record. Now, I must wait a full six months in my own home before the courts will consider a new custody plan for my two little girls.

Another big hurdle with a felony conviction is employment. Right now, I work as a cosmetologist and a waitress to make ends meet. Ideally, I’d like to get my realtor’s license, but I am restricted from applying for it and many other career fields.

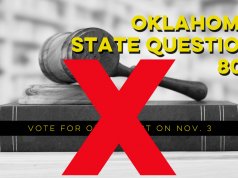

But, change is happening in Oklahoma to address the long-term consequences of felony convictions for low-level offenses and the state’s growing prison population. Voters and the Oklahoma Legislature approved SQ 780 and SQ 780 retroactivity to change low-level drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. SQ 780 is already in effect and on Nov. 1, SQ 780 retroactivity goes into effect so more than 60,000 Oklahomans can apply for expungement to remove these felony convictions that are now misdemeanor offenses.

SQ 780 retroactivity is going to be life-changing for tens of thousands of Oklahomans, their families and communities. Unfortunately for me and many others who are getting our lives back together, the expungement fee (minimum of $1,000) is just too high. For those that can access and benefit from expungement, they will have so many more opportunities to get a great job, stable housing, education and financial assistance opportunities to become productive citizens and create a better life. Once I save enough money, I hope to apply for retroactivity, so I too can provide a better life for my two little girls and myself.