Since Congress approved the Paycheck Protection Program in April, the Small Business Administration has guaranteed more than $500 billion in loans to businesses trying to keep themselves afloat and workers employed during the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Meanwhile, the banks loaning the funds have been benefitting from the fees associated with the loans.

A study by New York University School of Law’s Institute for Corporate Governance & Finance and Colleen Honigsberg of Stanford Law School estimated banks could earn as much as $24 billion in fees as a result of PPP loans.

The biggest banks stand to earn the most money, with Chase and Bank of America estimated to make a combined $1.5 billion to $2.6 billion in PPP loan fees.

“It could be enormously profitable for us, maybe the most profitable thing we’ve done,” Rick Wayne, president and CEO of Northeast Bank told S&B Global Market Intelligence last month.

Thus far, American banks have loaned approximately $521 billion to businesses large and small. In addition to fees, banks are allowed to charge up to 1 percent interest over the lifetime of the loans, which are also fully backed by the federal government.

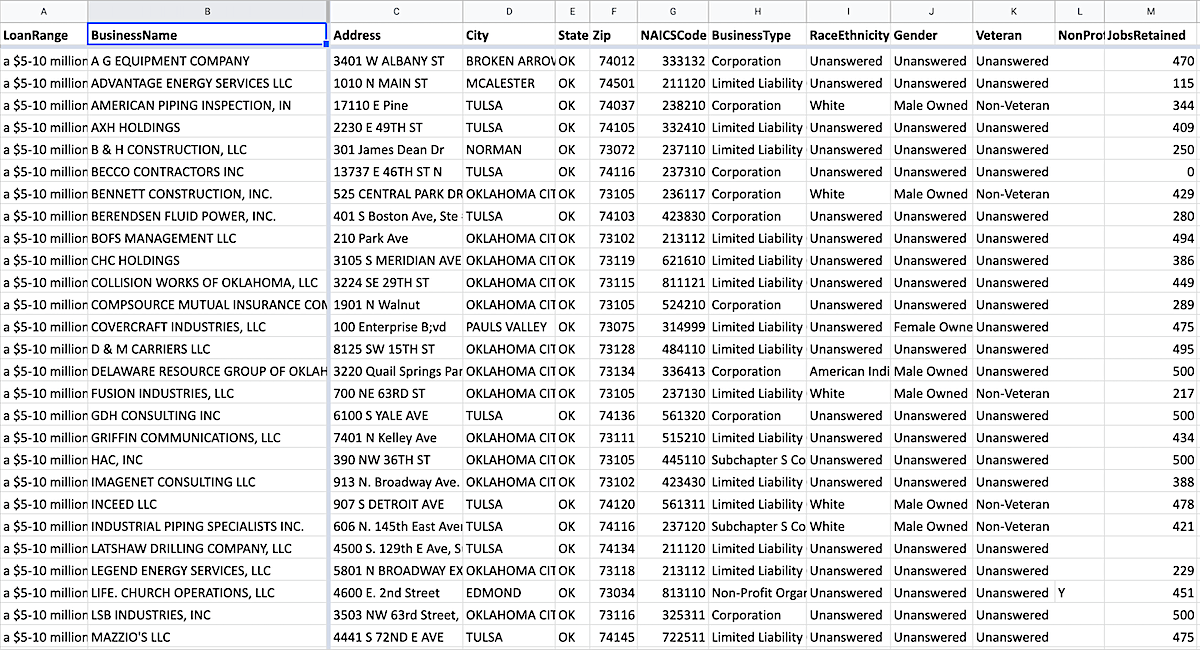

Last week, the Small Business Administration released detailed data on the 4.9 million PPP loans made across the country so far, including about $5.5 billion distributed to more than 64,000 Oklahoma entities. (The SBA will eventually determine if borrowing entities qualify for the loans to be forgiven.)

A glimpse of Oklahoma banks’ PPP portfolios

Under rules set by the U. S. Department of the Treasury, banks can levy processing fees from 1 to 5 percent on PPP loans. The highest percentage fees are charged for the lowest loans, below $350,000, and the lowest fees apply to the highest loans.

The median fee is about 3 percent according to a study by New York based Keefe Bruyette and Woods, an investment firm that looked at PPP loans from more than 200 lenders. For loans issued to small businesses, the banks’ fees are paid by the federal Small Business Administration.

Oklahoma banks and those that have a heavy presence in the state have made millions in fees from the PPP program.

For instance, BancFirst, Oklahoma’s largest state-chartered bank, has distributed $209,545,105 in loans of less than $150,000, according to the numbers released by the SBA. Since those loans fall on the lower end of the scale, the bank could have charged 5 percent in fees, which would have brought in more than $10.4 million in fees.

It is more difficult to estimate the fees on larger loans, however, because the precise amounts of those loans were not released by the SBA.

Still, 44 PPP loans of between $5 million and $10 million (the highest category) were distributed in Oklahoma. If, for the sake of rough estimation, those loans averaged $7 million and came with a 1 percent fee, they would account for $308 million in distributions and $3.08 million in fees.

In that highest category of loan amounts, 27 of the loans came from Oklahoma-based banks.

Examined at a more granular level, the fees can look more modest, and they often involved small, local banks. For example, The Spud Company in Felt received a loan of between $150,000 and $300,000 from Happy State Bank. Hines Location Lighting received a loan in the same range from Pauls Valley National Bank. Each lending institution could have made as much as $9,000 on those loans.

Paul Monies of Oklahoma Watch noted that five banks accounted for one-third of PPP loans in the state:

BancFirst led the way, with more than 950 loans. Next was Arvest Bank (483), Bank of Oklahoma (354), MidFirst Bank (269) and First United Bank and Trust Co. (243). Those five banks accounted for one-third of the PPP loans above $150,000. The same five banks accounted for one-third of the PPP loans in the loans of less than $150,000.

How banks make money

In the early days of the pandemic, the federal government considered having the Small Business Administration be the direct conduit of PPP loans, but that idea was quickly scrapped in favor of processing loans through banks.

Oklahoma State University finance professor Nancy Titus-Piersma said efficiency would have been among the chief concerns when it came to doling out loans.

“I think, when you look at it, the PPP loans were set up very quickly,” she said. “The SBA is a government agency that makes loans to businesses, but it’s really too small to handle the volume of loans. That left banks, which already had the infrastructure in place and knew the landscape.”

RELATED

Search the Oklahoma recipients of PPP money by Tres Savage

Titus-Piersma said the fees banks charge for the loans are in line with fees on regular loans. She argued the banks should be able to make money for their time, and the leg work necessary to process loans.

“Quite honestly, if the government had not given banks an incentive through fees, they likely would not have participated in the program,” she said.

Banks, like grocery stores, deal in high volume. Institutions often face thin profit margins, and they make money in two ways — interest and fees.

Titus-Piersma said the fees that banks charge for overdrafts, ATM withdrawals and checking accounts don’t typically cover all of their operating expenses.

“When the bank charges you an ATM fee or a bounced-check fee, there’s really almost never enough fee income to cover the overhead,” she said. “It’s very common that interest income has to support the rest of the operations.”

The profit margins are heavily reliant on maximizing loans.

“The margins are usually pretty thin,” Oklahoma Bankers Association vice president Adrian Beverage said. “It’s a volume business.”

The sheer magnitude of PPP loans has increased that volume substantially across the banking industry in 2020.

Some banks to donate fees

For its part, Bank of America has said it is planning to donate all fees it earns from PPP loans.

“We will use the net proceeds of fees (…) to support small businesses and the communities and nonprofits we serve,” a Bank of America spokesman told the Wall Street Journal.

Titus-Piersma said the fee numbers might look big, but they are also typical of how banks always operate.

“I don’t think those loans would have been made if not for that program, so yes, the fees look big, but what you need to understand is that’s how banks make money,” Titus-Piersma said. “And they can only make 1 percent interest on the life of that loan. I think that’s pretty reasonable.”

Beverage said $500 billion being pushed through a program in a small amount of time skews the overall picture.

“The numbers look so high because of the sheer volume of loans in a very short amount of time. It’s a very impressive amount,” he said. “But if you look at a small community bank that employs a handful of people, those kinds of banks really stepped in most of all and got a lot of loans processed that allowed businesses to stay open. They deserve a pat on the back because it was a big job, and they don’t have the employee resources a Bank of America or a Chase has.”

Titus-Piersma said institutions like Bank of America, or, more regionally, BancFirst and Bank of Oklahoma, might have made more money and stood out on spreadsheets, but it has been the small community banks that helped the PPP loans make an impact.

“The small and medium sized banks are crucial,” she said. “I worked for large banks, and those banks wouldn’t touch a lot of these businesses. The smaller banks will. They’re a lifeline to small business.”