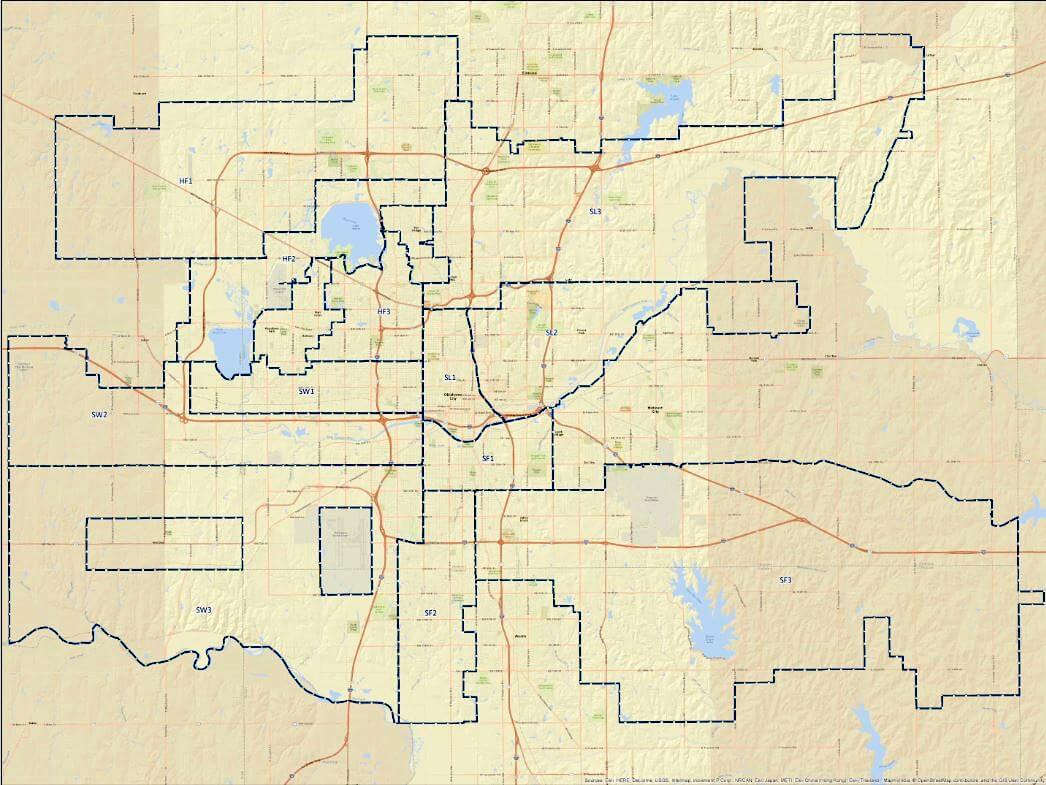

An unusual dispute between district court judges and the Oklahoma City Police Department over the law enforcement agency’s 30-year practice of holding certain arrestees in the Oklahoma County Jail — even when arrested for crimes in other counties — is brewing before the state Supreme Court.

The matter arose after Cleveland County District Judge Thad Balkman issued an administrative order April 1 requiring that all persons arrested for crimes allegedly committed and triable within Cleveland County be detained at the Cleveland County Detention Center. Balkman’s order was followed on April 10 by a similar one from Canadian County District Judge Jack McCurdy II.

Oklahoma City police patrol beyond the borders of Oklahoma County because the Oklahoma City limits extend into Cleveland, Canadian and Pottawatomie counties. But for many years, all persons arrested by OKCPD have initially been held in the Oklahoma County Jail, no matter where the alleged crime occurred. Those detainees stay in the Oklahoma County Jail until formal charges are filed by district attorneys, at which point they are transferred to the jail in the county where charges have been filed. (The City of Oklahoma City does not maintain a municipal jail.)

OKCPD did not immediately follow Balkman’s instructions, and the city challenged the April 1 order. Lawyers for the Oklahoma City Police Department claim district judges lack the authority to tell the police where they can hold arrestees in custody before charges are actually filed. Meanwhile, Balkman, McCurdy and other district judges have accused the police department of illegally and intentionally violating the two orders. They also argue that transfer delays by the OKCPD violate criminal defendants’ rights to promptly see a judge.

“Even in the best of circumstances where the probable cause affidavits are timely submitted, a person taken to the Oklahoma County Jail spends several days longer in jail than a person taken to the appropriate detention center,” Cleveland County District Judge Lori M. Walkley wrote in one court filing.

Attorney General Mike Hunter has already tried and failed to mediate the dispute, and the judges involved have accused OKCPD of reneging on a settlement deal. Oklahoma City Police Chief Wade Gourley has also been threatened with possible bench warrants for his arrest if he failed to appear at court hearings to explain his department’s refusal to abide by orders from judges in Cleveland County and Canadian County.

While the matter was first taken up by the state Court of Criminal Appeals, that court punted it to the Oklahoma Supreme Court on June 29, finding that the issue appeared to be a civil matter outside its jurisdiction even though the administrative order pertained to criminal arrestees. The Court of Criminal Appeals left it to the state Supreme Court to decide which court has jurisdiction.

The City of Oklahoma City is expected to file its argument with the Oklahoma Supreme Court this week.

‘Efforts to cure this practice have gone unheeded’

Balkman’s April 1 directive was part of a larger order to address the risk of coronavirus spread by the transfer of prisoners from the Oklahoma County Jail to the Cleveland County Jail and courthouse. Because of the pandemic, Balkman and McCurdy also directed that those detainees already in the Oklahoma County Jail not be moved because of the risk of spreading the virus.

“The long-standing practice of certain municipalities within Canadian County to transport arrestees to the Oklahoma County Jail for offenses allegedly committed and triable within Canadian County has never been sanctioned nor condoned by the Canadian County Sheriff’s Office, the Canadian County Board of County Commissioners nor the Canadian County judiciary except as evidenced by any written contract to accept inmates pertaining to the two detention facilities, if any,” McCurdy wrote in language mirroring Balkman’s order. “Absent an agreement to the contrary, the practice shall immediately cease and the detention of any person so arrested shall be conducted according to statute.”

The judges contend some persons have been held more than 20 days in the Oklahoma County Jail before courts in either Cleveland or Canadian counties became aware of the arrests.

“Decades of efforts to cure this practice have gone unheeded,” Walkley wrote in a pleading with the Court of Criminal Appeals.

Walkley argued the OKCPD had “illegally detained” persons in the Oklahoma County Jail. She said Cleveland and Canadian county sheriff’s deputies had been advised that if they did not pick up those persons the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Office would “cut them loose” owing to the pandemic.

In a petition filed with the Court of Criminal Appeals seeking an order barring enforcement of Balkman’s administrative order, city attorneys explained that the reasons for preliminary detention of arrestees in the Oklahoma County Jail are numerous. They said the OKCPD has secure rooms for drug testing, detective interviews and collection of evidence at the Oklahoma County Jail and that computer systems there tie into the OKCPD records management system.

The city attorneys also stated that an expedited booking process at the Oklahoma County jail allows officers to return to service quicker, thereby allowing an increase in police presence on the streets. The city contends those advantages are not available at the Cleveland or Canadian County jails.

Although the district court judges claim the OKCPD ignored Balkman’s administrative order, it did get the city’s attention.

On April 9, OKCPD legal advisor Stephen Krise prepared a memo to Cindy Richard, OKC’s deputy municipal counselor, outlining his legal research on the issue. He concluded the police could lawfully bring persons arrested outside Oklahoma County to the Oklahoma County Jail.

That research formed the basis for the legal arguments brought by city attorneys challenging Balkman’s order. But that challenge did not occur until May 27, when the city filed a motion to vacate the judge’s order in Cleveland County, by which time McCurdy had already filed his order, leaving the OKCPD fighting two orders simultaneously.

The basis of the arguments

The statute relied upon by the judges for their legal authority commanding the OKCPD to avoid the Oklahoma County Jail has been on the books since 1910.

“When his personal appearance is necessary, if he be in custody, the court may direct the officer in whose custody he is to bring him,” states Title 22, Section 435 of Oklahoma statutes.

Also, the judges rely upon rules issued by the Supreme Court that grant the district court’s presiding and chief judges with supervisory authority over “the work of the courts” and “the operation of all courts in the judicial administrative district to assure adherence to statewide court objectives and policies.”

“It is difficult to imagine,” Walkley wrote, “that the ordering of detainees to be brought upon arrest to the appropriate county so that the constitutional and statutory mandates of due process may be adhered to is not ‘the work of the courts.’”

When city attorneys filed motions to vacate the Cleveland and Canadian County orders, they argued state statutes require that municipal police place arrested suspects in custody of the sheriff’s jail in the county where the crime happened only for non-bailable offenses — which in practice means only for first-degree murder.

The city relied upon a 1984 state attorney general opinion that concluded statutes are silent as to who is responsible for holding all other criminal suspects until formal charges are filed.

That opinion, by then-Attorney General Mike Turpen, held that because no statute established the responsibility for detention of state law violators arrested by municipal police pending formal charges by the state, the matter must be resolved between city and county authorities and, until that agreement is reached, the city police department is under a duty to secure the arrestee.

Moreover, the attorneys contend Oklahoma City police can legally hold the arrestee in the defacto city jail, which by contract is the Oklahoma County Jail.

Deal or no deal? Judge claims OKCPD backed out

A hearing before Balkman on the city’s motion to vacate his order was scheduled for July 9. The judges later filed a pleading criticizing the city attorneys for scheduling a hearing without the court’s permission.

Meanwhile, Canadian County District Judge Paul Hesse had issued orders to OKCPD Chief Wade Gourley to deliver to the Canadian County Jail in El Reno two persons arrested in Canadian County by Oklahoma City police and held in the Oklahoma County Jail for two weeks without appearing before a judge. Title 22, Section 181 of state statute provides that a defendant must, in all cases, be taken before a judge “without unnecessary delay.”

Hesse’s order also stated that Canadian County Sheriff Chris West announced he would no longer transport Oklahoma City arrestees from the Oklahoma County Jail to the Canadian County Jail without an order commanding him to do so.

On June 22 and June 29, OKC attorneys and the judges met with Hunter, the state attorney general, in an attempt to resolve what was turning into a major legal dispute between the courts and the police. The effort appeared to be an attempt to follow Turpen’s opinion that city and county authorities would need to work it out.

In a pleading filed weeks later, Walkley stated the judges believed a tentative resolution had been reached during the attorney general’s mediation, whereby the OKCPD would transport persons arrested in Cleveland and Canadian counties for crimes committed or triable in those counties to the detention facilities there within 12 hours of arrest.

But on July 6, Hunter and the judges received an email from Oklahoma City Police Deputy Chief Jason Clifton containing what Walkley believed would be language of the agreement, only to find that the city had made another proposal — that police would deliver prisoners within 24 hours or the next business day after charges were accepted by the district attorney, and until then arrestees would remain city prisoners in the Oklahoma County Jail. The city also proposed a video connection to satisfy the right to appear before a judge.

The judges told Hunter that was unacceptable, and negotiations ended.

Later that day, Balkman cancelled the July 9 hearing and denied the city’s motion to vacate his administrative order.

Balkman referred to Oklahoma City’s motion as merely a “public comment.” The judges explained later that a “motion to vacate” is not permitted by procedural rules and the only remedy the city had was to appeal to a higher court, making the city’s motion a legal nullity.

McCurdy likewise struck from his docket a hearing on the city’s motion to vacate his order in Canadian County, and he denied the city’s request.

Judges to OKCPD chief: Show up to court or be arrested

Before city attorneys filed their appeal, however, judges in both counties began issuing transport orders commanding Oklahoma City police to deliver specific arrestees to their respective county jails, including those who had recently been booked into the Oklahoma County Jail.

The orders contained language requiring Gourley, the OKCPD chief, to appear in their court for “show cause” hearings to explain why the April administrative orders had been ignored. Such hearings are usually preliminary to a court finding a summoned person in contempt of court.

The orders all stated that Gourley had to appear or a bench warrant would be issued for his arrest.

The first order, from Special Judge Steve Stice, came on a Sunday night, July 19, regarding a DUI suspect arrested in Cleveland County two days earlier but booked into the Oklahoma County Jail. Stice sent the order by email to the city lawyers commanding the suspect be brought to the jail in Norman within 24 hours and that Gourley appear in his court that Tuesday afternoon.

This led to a flurry of court filings on Monday, when the city filed an objection to the order and filed its petition for writ of prohibition of Balkman’s order with the Court of Criminal Appeals. The city also asked the appellate court to stay the proceeding before Stice so that Gourley would not have to appear as ordered.

But a stay did not come, and Gourley appeared before Stice on July 21.

OKC assistant municipal counselor Katie Goff later described the hearing as having an “ambiguous nature,” but she said the court assured the city it was not a contempt proceeding or a criminal proceeding against Gourley and that it was not the court’s intention to seek contempt against him, his lawyers or any Oklahoma City representative.

The Norman Transcript reported that, during the hearing, Stice recalled a case where a woman was held in the Oklahoma County jail for 27 days prior to appearing before a judge.

“We have an issue that is a competing interest between your process and the rights of defendants and the victims of those alleged crimes,” the newspaper quoted Stice as telling OKC assistant municipal counselor Richard Mann.

On July 27, Stice wrote an order stating the Oklahoma City municipal attorneys had promised police would abide by Balkman’s April 1 administrative order, but that after the hearing he learned of two new cases where persons were arrested by OKCPD in Cleveland County and held in the Oklahoma County Jail.

He ordered Gourley to appear again on July 31, which was to be Stice’s last day on the bench before returning to private practice.

Goff then filed a motion for an emergency order asking the Court of Criminal Appeals to stop Stice from having the hearing.

“The Oklahoma City police chief cannot continuously and with minimal notice be hauled into court under threat of warrants, contempt and jail when he is, to his knowledge complying with the agreement mediated by the attorney general and agreed to by the parties,” Goff wrote. “Additionally, it is of note that the nature of the July 21, 2020, proceedings seemed unusual and potentially animus, likely due to Judge Stice being a party in opposition to the city in this matter.”

In an objection filed by the judges, Judge Walkley stated the Oklahoma City Police Department had been disregarding the orders for more than 90 days and was too late to complain about them now.

The objection also delved into the reason for the court’s administrative orders, which included avoiding spread of the novel coronavirus and protecting arrested persons’ constitutional rights, which the judges believed were at risk due to delays in OKCPD bringing detainees held at the Oklahoma County Jail before a judge.

“While the courts are named opposing party in this [appeal], the courts are acting on behalf of the interests of justice and thus the risk of harm to the public interest is equally implicated,” Walkley wrote. “Persons detained by [the City of Oklahoma City] are often held in the Oklahoma County Jail for days without the benefit of a bond setting, the ability to obtain counsel, particularly if indigent, or to appear before a magistrate.”

To the Supreme Court

The Court of Criminal Appeals then transferred the appeal to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, without halting any of the district court proceedings involving Gourley.

A day later, McCurdy telephoned Goff to let her know he had ordered Gourley to appear for a “show cause” hearing in his courtroom Aug. 4 to explain why there was yet another probable cause affidavit submitted to him for a person arrested by Oklahoma City police in Canadian County but being held in the Oklahoma County Jail in violation of the court’s order.

Goff stated in a court filing that she refused to accept service of the order on behalf of Gourley. But later that morning, Gourley told her he had received notice of the order “to appear and show cause why he should not be held in contempt.”

Gourley was then faced with two upcoming court-ordered appearances — one in El Reno and one in Norman.

But on July 30 — the eve of Gourley’s hearing before Stice in Norman — Oklahoma Supreme Court Chief Justice Noma Gurich brought the rush of court filings and hearings to an abrupt halt.

Gurich granted the city’s request to stay enforcement of the Cleveland and Canadian county administrative orders issued in April and stopped all further hearings, except for district court orders to bring defendants to court for arraignment.

Gurich specified that she was not deciding whether the Supreme Court had jurisdiction to decide the case, but rather that Oklahoma City and the judges were directed to file further pleadings to address the jurisdictional issue and the issue on the merits.

Those pleadings will come Tuesday, Aug. 18, and Tuesday, Aug. 25. An oral presentation of both sides’ arguments will be made by telephone to a Supreme Court referee on Sept. 1.

However, McCurdy issued a writ of habeas corpus in two felony cases on Aug. 4 commanding Oklahoma City police to deliver defendants to the Canadian County jail effective “immediately,” indicating the OKCPD practice of holding persons arrested for crimes in other counties in the Oklahoma County Jail continues at least a while longer.