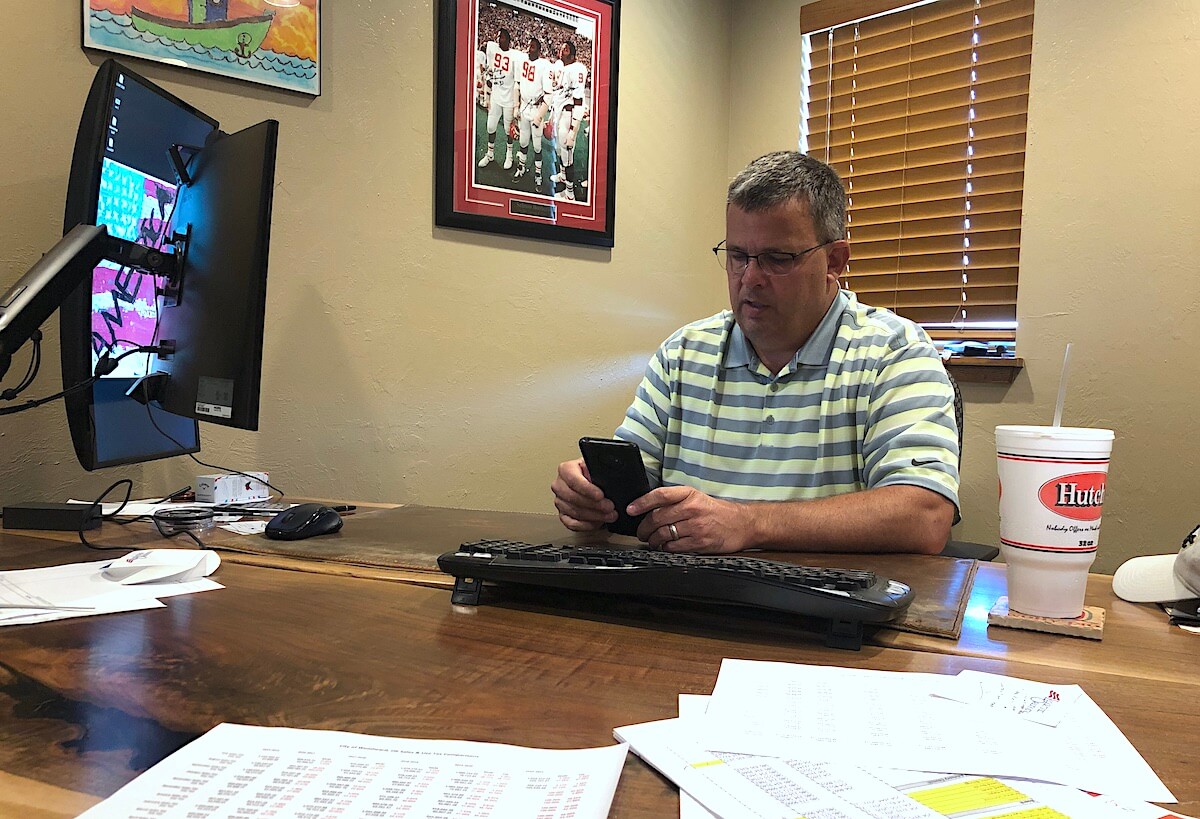

WOODWARD — Alan Case has a theory about Woodward County.

“I think if you interviewed 100 people on the street corner and said, ‘Which is worse: The economic downturn or COVID-19?’ I think 95 people would say, ‘The energy economy,'” said Case, who has been president of the Woodward Industrial Foundation since December 2016.

When Case started at the economic and community development entity, the economic outlook was turning sour for Woodward, a roughly 12,000-person town in northwestern Oklahoma whose mottos is “Energy for Life.”

The energy industry has historically been Woodward’s primary economic engine, and when oil prices plummeted at the end of 2014, Case and others did what they could to limit the impact and bring new employers to the area.

“It was like catching a falling knife,” he said. “There wasn’t a lot to be done about it.”

When energy prices were high, Case said, Oklahoma’s largest oil and gas companies — those that drill and those that provide oilfield and midstream services — operated satellite offices across western Oklahoma.

“All of those companies realized they could no longer afford that business model, so they pulled their satellite offices out of Woodward,” Case said. “So we were losing jobs 40 and 100 at a time for two and a half to three years, and it resulted in a negative migration of about 4,000 people out of Woodward, Oklahoma, over that same time period.”

While 2020 has seen Chesapeake Energy file bankruptcy and oil prices briefly dip into negative numbers, Case said the impact in Woodward County was old news.

“Energy comes and goes, and we’re glad to have it in Woodward,” he said. “It’s been a cornerstone of the state for decades. But when it leaves, it leaves abruptly and without apology.”

COVID comes sweeping down the plains … sort of

When the novel coronavirus pandemic became an Oklahoma reality in mid-March, it seemed to arrive abruptly, without apology and without concern for whether a state’s public health laboratory could process 50 tests per day or 50,000. For Oklahoma it was the former, and decades of drama at the State Department of Health finally manifested into tangible concerns with deadly consequences.

For a brief time in March, it looked like Woodward might be hit by the pandemic as suddenly and heavily as many other American communities had been. According to OSDH data, Woodward County saw its first positive test for SARS-CoV-2 on Friday, March 13, two days after members of the Utah Jazz basketball team tested positive in OKC and caused the shutdown of the NBA season. At the time, it was one of only a handful of positive tests in the state.

The dominoes fell quickly. The Oklahoma Legislature adjourned indefinitely March 17, the same day that Oklahoma City closed bars, restaurants, gyms and other businesses. Tulsa, Norman and other communities followed suit, and four days before Gov. Kevin Stitt announced his statewide conditional restrictions on businesses on March 24, Woodward Mayor John Meinders issued his own proclamation mandating the closure of certain businesses, including bars, gyms, theaters and restaurants for sit-down dining.

“Very early on, we were visiting with local physicians on how to translate what information we were receiving from the state to what is locally going on. This was before testing,” said Woodward City Manager Alan Riffel. “The message we were receiving was take all precautions as early as possible. We did. We went through one week in mid-March where we went from an encouraging standpoint to a mandatory standpoint in terms of protocols.”

But unlike Oklahoma’s major metro areas and other communities in the state, Woodward County did not see another confirmed case of COVID-19 until May 14, two full months after its first positive test. When Stitt unveiled a statewide timeline for reopening, Woodward followed suit.

“As far as why we have seen such minimal impact here as far as direct experience, I think is the fact that those actions were taken early and continued, but it also has to do with our lifestyle here,” Riffel said. “There are a lot of independent people who are used to solitary circumstances. People can quarantine fairly simply.”

In the three months since mid-May, Woodward County has seen only about 50 other cases, equating to only 0.25 percent of the population. No one has died there from the respiratory disease so far — knock on a Woodward County cottonwood.

“In a lot of our more rural areas like we have in northwest Oklahoma, we’ve seen less impact,” Deputy Commissioner of Health Keith Reed said in a phone interview Thursday. “Woodward County has done relatively well. I know that there has been impact in the community even though there has not been a whole lot of cases. That’s kind of a regional hub there that helps serve surrounding counties.”

Terri Salisbury knows all about the counties surrounding Woodward. The State Department of Health’s regional administrative director for 10 counties in northwest Oklahoma, Salisbury has been with the Woodward County Health Department since 1996.

“The hospital and the emergency manager along with the health department, the city and county — we’ve worked together to educate and keep the community informed on the status of the positives and prevention measures,” Salisbury said. “I think they’ve done a very good job of managing it.”

She said most of the area’s COVID-19 testing has been conducted by Xpress Wellness Urgent Care and the Woodward County Health Department, which also serves Ellis, Dewey, Roger Mills and Cimarron counties. Aside from the May outbreak tied to a Guymon meat-packing plant, Salisbury’s northwest Oklahoma health department district has avoided major spread of the coronavirus.

“The primary thing we are [trying to do] is to avoid becoming complacent about the methods to decrease transmission,” she said. “[We] encourage the wearing of masks like our grocery stores are continuing to do — social distancing and one-way shopping in the stores. So they’re still doing a lot of the preventive measures, even though our numbers haven’t been real large.”

As a longtime resident of Woodward, however, Salisbury said she also understands the need to keep the local economy moving.

“I definitely think that concern is in the community,” she said. “Especially the restaurants and smaller businesses. Not only with the oil (industry) decrease, but the COVID (pandemic) having limited some of their business, it has affected our economy.”

‘If I make money, I save it’

For decades, Maxine LaMunyon has sold women’s clothes in downtown Woodward. Asked how long she has run Maxine’s on Main Street, she simply says, “Forever,” although an article in The Oklahoman says she opened the store in the late 1980s.

“It’s been very, very slow,” LaMunyon said of her store since the pandemic hit. “It affects everybody. But you’ve just got to hang in there and do what you can do. Come to work at certain hours you’ve been coming to work. Closing at certain hours. And be here for everybody.”

LaMunyon, an octogenarian who said she is not particularly worried about catching COVID-19, knows that some of her fellow small business owners have struggled with this year’s economic slowdown. But not her.

“I’m always prepared,” she said. “I’m a person who, when you make money you save it. And when your hard times come, then you have money to fall back on. You don’t have to worry about closing your store down or laying your help off or nothing because you are financially OK.”

Five months after the temporary closures, Woodward’s municipal government itself is more “financially OK” than some projected it would be. For July and August (the first two months of this fiscal year,) data provided by Case of the Woodward Industrial Foundation show only small declines in sales taxes compared to last year. Collections of use taxes, however, are up significantly and have evened out the sales tax slump. Case said he suspects a greater reliance on online shopping is reflected in the numbers.

“We really thought with COVID coming that it was going devastate our sales tax revenues, and it really hasn’t. We might be down 10 percent, but the fear was 25 percent,” Case said.

Riffel, the city manager, agreed. But he pointed to the economic struggles his community was already facing.

“We have been in a decline economically here for sales tax revenues for the past five years,” Riffel said. “This has been the fifth year that the city has furloughed people for 10 percent. We have essentially 36-hour work weeks now. Our economy was already feeling the trend of what energy was doing, and then when energy really bottomed out.”

Riffel said city leaders anticipated that the pandemic would greatly exacerbate the slumping economy.

“We have virtually no capital projects budgeted for this coming year,” he said. “However, the first two months of this fiscal year aren’t indicating that significant of a decline. We are basically flat of where we were a year ago.”

Senator watching U.S. Census response rate

Sen. Casey Murdock (R-Felt) represents Woodward County in the Oklahoma Legislature, and he is watching the economy and the pandemic across his sprawling district.

“I think the people up here are more afraid of the economy than they are of catching COVID,” Murdock said by phone while working cattle. “The lack of drilling activity in western Oklahoma is putting a squeeze on the economy in northwest Oklahoma, not just Woodward. People are more afraid of losing their jobs or not getting another job than they are of catching COVID.”

Murdock said he is not yet sure how much the federal CARES Act will have ultimately helped out his district, but records show at least 61 Woodward businesses received more than $150,000 each in Paycheck Protection Program loans, which are potentially forgivable if employers retained their employees.

As Gov. Kevin Stitt allocates additional CARES Act money across the state, Murdock has a separate concern: the relatively low rate of response to the 2020 U.S. Census in his district.

“What concerns me is we are down from where we were 10 years ago as a percentage-wise. At first I was kind of concerned people were just not filling out the census,” Murdock said. “Now I’m wondering if they’re not filling it out because they don’t care, or are they not filling it out because they’re not there? I fully expect to see a decline in population, but I just don’t know how big a one. If we can break even, I’ll feel good. Guymon has grown, but Woodward is struggling.”

Statewide mask mandate ‘would be poorly received’

While its economy may be up against the ropes, Woodward may be Oklahoma’s largest community to avoid a COVID-19 outbreak so far. When school resumed last week, students were in classrooms ready to resume the instruction and socialization they missed out on when classes were moved online in April. The local district has adopted a tiered set of school safety protocols, and the superintendent has been given discretionary authority to modify the plan as needed.

“I know that they are taking into account if the new positives are associated with the school vs. a long-term care facility,” said Salisbury, the State Department of Health’s regional administrator.

Case hopes Woodward can continue to balance safety with the need to have a somewhat normal society. He offered a series of anecdotes about people being responsible during the pandemic, including his attendance of funerals where he knew some seniors had chosen to stay home.

“It’s been amazing living here and watching the tolerance of people with each other and the responsible nature that they socially distance themselves,” he said. “We’re not the greatest mask wearers in the world, but we do understand that we live in an area that is pretty isolated to begin with.”

Case and Riffel both said they believe their community appreciates that Gov. Kevin Stitt has mostly avoided statewide mandates related to the pandemic.

“It would be poorly received here to try to implement a mandatory mask (rule). I think we would have some distinct opponents to that. I understand both sides of that argument. I personally mask up as much as possible in public places,” Riffel said. “People who live in western Oklahoma are pioneering type of people anyway, and they treasure their independence. We were challenged with some segment of local (residents) — even an attorney who wanted to challenge what protocols we set down in the first place. It’s a question that has strong feelings on both sides.”

Case said he believes most Woodward residents value local control. Most of Oklahoma’s larger metro areas have passed some sort of mask mandate at the municipal level.

“I think most people out here felt like there should be some flexibility for areas that appear to have it under control and that a [statewide rule] was largely unnecessary. Some of the extreme measures I think would have been met with a lot of resistance in areas that are this rural.”

Still, Riffel, Case, Salisbury and others are continuing to push responsible and sanitary behavior. The same goes across the state’s panhandle, as The Frontier’s Ben Felder reported about growing concerns in Cimarron County, which has seen only 11 total cases so far.

“The main message is to please use preventive measures: Social distancing, wearing a mask — all those things do pay off,” Salisbury said. “My staff and I have been working full-time since this started, and we correctly mask and gown when we need to, and we have not tested positive.”

Salisbury said the Woodward County Health Department offers free, drive-up testing and averages about five to 15 tests per day.

“It does pay to use preventative measures. And we encourage people if they do feel ill to stay home,” Salisbury said. “Staying in and isolating is the biggest thing they can do for the community to stop the COVID spread.”