State law holds strict rules preventing elected officials from using public resources for campaigning. Traditionally, this has meant that officeholders cannot solicit or receive donations in state-owned buildings or use state-owned phones or email accounts to conduct campaign business.

When it comes to social media, however, the rules are not as well established, and many incumbents often stray into ethically ambiguous territory by using social media both to communicate with their constituents and to promote issues and campaigns.

Social media regulation is a relatively new body of campaign finance rules — Oklahoma’s rules have only been in place since 2015. Making matters more complicated, the Oklahoma Ethics Commission releases clarifying interpretations of the rules only after challenges arise, so campaigns must currently interpret rules for themselves.

It’s clear, by looking at a suite of incumbent candidate accounts, that interpretations of the existing regulations vary. Some campaigns appear to follow the examples given in the ethics guide to a tee, creating separate accounts for their campaigns and official business. Others fairly obviously violate the spirit, if not the letter, of the rules by mixing official updates on coronavirus or legislative matters with requests for donations or information on picking up campaign signs. A solid number sit somewhere in the middle, occupying a gray space that may not be decided until a complaint brings the issue to a head.

A survey of some elected officials’ various social-media accounts reveals the ways in which officeholders navigate these murky regulations and raises questions about whether it might be an area subject to widespread ethics violations.

What the rules say

According to Rule 2 of the Oklahoma Ethics Commission rules, officeholders and their employees cannot use state resources or their official communications to campaign for any elected state office or ballot initiative. For instance, no one can ask for donations, receive donations or display campaign materials in the State Capitol or any other state building.

In terms of communications, Rule 2.11 says state resources can be used to inform constituents of state business “provided those materials do not advocate the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate or candidates for any elective office or offices or a vote for or against a state question or other question to be voted upon at an election.”

An annotation by the Ethics Commission clarifies that official communications may include an officeholder’s opinion on a bill or issue.

“Such activity is permissible as long as these communications do not include overt campaign communications,” the annotation on Rule 2.11 reads.

Resources such as phones, email and any other state property or services explicitly may not be used to advocate for the election of any candidate, according to Rule 2.14. That rule has implications for social media use. For instance, an elected official is prohibited from using their state email to set up a campaign account or ask a state employee to maintain it for them. These sorts of violations, if they do occur, would be largely on the back end and not visible to the public.

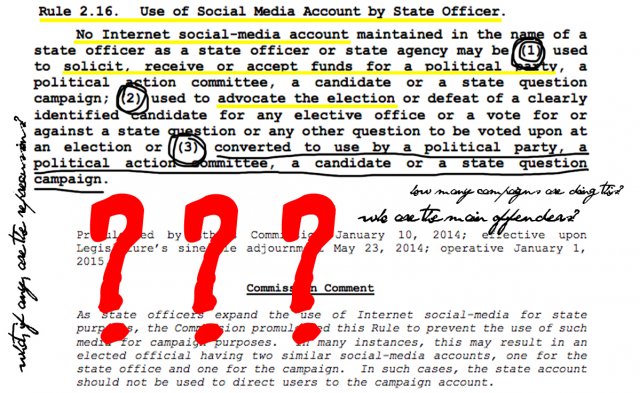

The main rule that deals explicitly with social media usage is 2.16. It reads, in its entirety:

No Internet social-media account maintained in the name of a state officer as a state officer or state agency may be (1) used to solicit, receive or accept funds for a political party, a political action committee, a candidate or a state question campaign; (2) used to advocate the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate for any elective office or a vote for or against a state question or any other question to be voted upon at an election or (3) converted to use by a political party, a political action committee, a candidate or a state question campaign.

The annotation by the commission indicates the intent of this rule was to prevent incumbents, who may have gathered a large following in the course of official business, from using that network to campaign, placing them at an advantage over non-incumbents and using their position as an officeholder for campaign purposes. A candidate, once elected, is allowed to convert a campaign account to an official account, but it can never be used for a campaign again.

“As state officers expand the use of Internet social-media for state purposes, the Commission promulgated this Rule to prevent the use of such media for campaign purposes,” the comment reads. “In many instances, this may result in an elected official having two similar social-media accounts, one for the state office and one for the campaign. In such cases, the state account should not be used to direct users to the campaign account.”

Meanwhile, there is no official prohibition against using a campaign page to post official business.

As legal challenges involving the ethics rules for social media arise, so should clarifications in the form of advisory opinions and court rules. But so far, Oklahoma doesn’t have any of these clarifications on the record.

Figuring out what the rules mean

Though a few actions are clearly prohibited by Rule 2.16, the distinction between an official and campaign account is not defined. Ethics Commission executive director Ashley Kemp and general counsel Stephanie McCord both said the commission could not comment about the situation, as discussing the topic publicly would constitute giving guidance improperly. This leaves lawmakers, candidates and citizens to use unofficial, common-sense criteria.

For instance, an official account might use the lawmaker’s official title, share official contact information, post updates on Capitol business or share information about their activity as an officeholder. Other possible factors could be if and how the account is used during the non-campaign season, whether the activity differs greatly during a campaign, whether there are any paid advertisements on the page and whether the account is verified.

In the Ethics Commission’s candidate guide for those seeking state office, the rules governing social media, including Rule 2.16, are applied to hypothetical situations. The situation for 2.16 describes a candidate who makes a page during their first election to use for campaign communications. Once elected, they then change the pages to say “Representative” and use it to communicate with constituents. The example explains that the page has changed to an official account, so it can no longer be used to campaign or be converted back to a campaign page.

Though this example provides another possible meaning of the rule when applied in real life, it is still only guidance and not an official interpretation.

Essentially, candidates and officials have only the information outlined here, as well as any conversations they have with consultants or Ethics Commission staff, to draw on when deciding how to use social media. That lack of clarity has led to wide-ranging approaches as candidates decide how to use social media to win votes while staying in compliance with ethics rules.

Two accounts, all campaign: What compliance might look like

The safest bet, many candidates seem to have decided, is simply to make two accounts, as the rules suggest, one for official purposes and one for campaigning.

Rep. Ronny Johns (R-Ada), for example, has an official Facebook account, which identifies him as a government official, uses his official picture and directs followers to his state email. It contains only (somewhat infrequent) official update posts about his work at the Capitol.

His campaign Facebook page, meanwhile, is called “electRonnyJohns.” It displays campaign graphics and directs followers to a campaign site. Johns has used the page since his initial election in 2016, and it remains fairly inactive between campaigns. The posts from this election cycle — in which he defeated his only challenger on June 30 — are nearly all campaign updates, rather than any information from the Capitol, and he has not recently shared any posts between the two accounts.

This set-up, according to the example provided in the ethics rules, is probably the safest way to ensure candidates do not accidentally or purposefully violate ethics rules.

Johns isn’t the only incumbent separating accounts. Among others, Sen. Roland Pederson (R-Burlington) and Sen. Greg McCortney (R-Ada) are following a fairly similar strategy.

Reps. Carol Bush (R-Tulsa) and Kevin McDugle (R-Broken Arrow) are taking a different route. The two incumbents each have only one Facebook account, but they seem to be marketing those accounts as campaign-related, rather than for official business.

Bush’s Facebook, which is clearly labeled as a campaign page, and the page’s title, “Carol Bush for State Representative HD70,” presents her as a candidate, rather than as an officeholder. But the page stays active between campaigns and shares what look like fairly official updates from the House, though the account does not appear to be connected to her office in any way.

Also walking this seemingly thin line, McDugle maintains a single Facebook page, titled “Representative Kevin McDugle House District 12.” The page contains a mix of campaign-related posts and updates from his work as a representative, but it explicitly says it is authorized and paid for by his campaign and directs followers to his campaign email, rather than his official one.

Though both Bush and McDugle seem to be following ethics guidelines, the absence of an official page forces constituents looking for Capitol updates to follow their campaign page. This can make the decision to have just one page, which many incumbents have made, a tricky one, especially if that page is not explicitly labeled as a campaign account, brands the candidate as an officeholder or includes updates on official business.

Over the line?

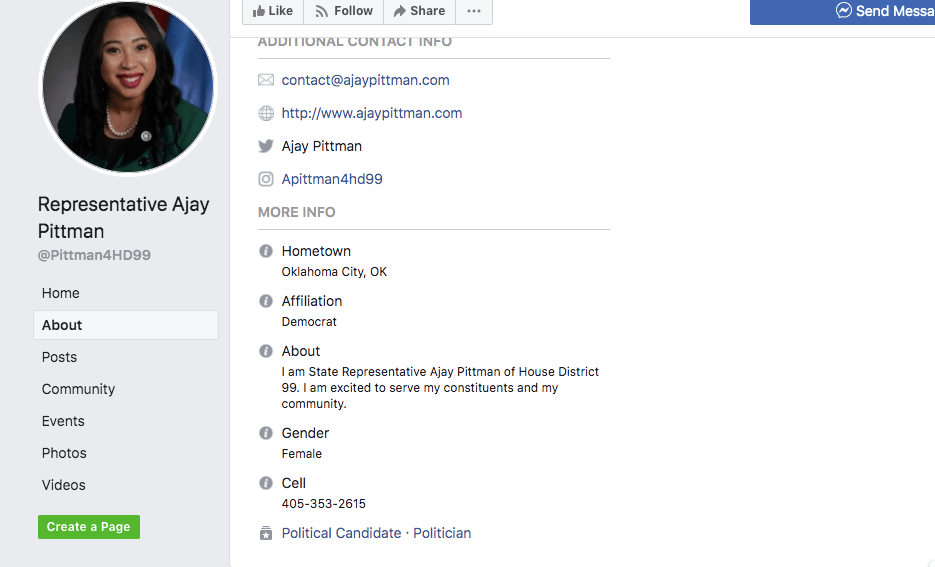

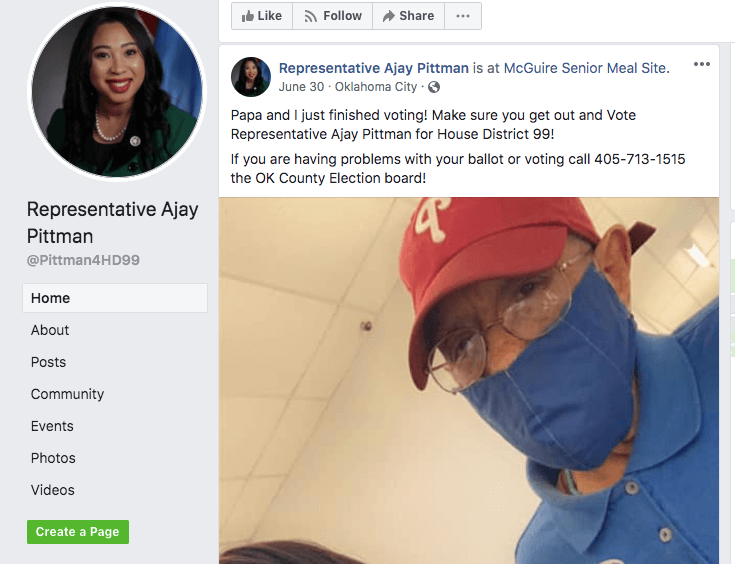

At first glance, Rep. Ajay Pittman’s (D-OKC) Facebook looks a lot like Bush’s and McDugle’s: one page with a blend of updates from the Legislature, district news, events, and campaign information. However, her account has one crucial difference. Not only is it not marked as a campaign account, it is labeled as the account of an elected official.

On Pittman’s About page, the categories of both politician and political candidate appear. Her biography reads, “I am State Representative Ajay Pittman of House District 99. I am excited to serve my constituents and my community,” and makes no mention of her campaign, though her banner includes the word “re-elect” and the page contains posts before June 30 asking followers to vote for her. (She won reelection against her only 2020 opponent in the June 30 primary.)

This mishmash of signals makes it difficult to tell whether the account is intended to be an official or campaign account, though a casual glance at the page would likely give one the impression it is the page of an elected official. Pittman is by no means the only legislator whose account falls in this confusing space, and, without binding guidance on what an official account looks like in practice, it can’t be definitively said that any of these incumbents are violating the ethics code.

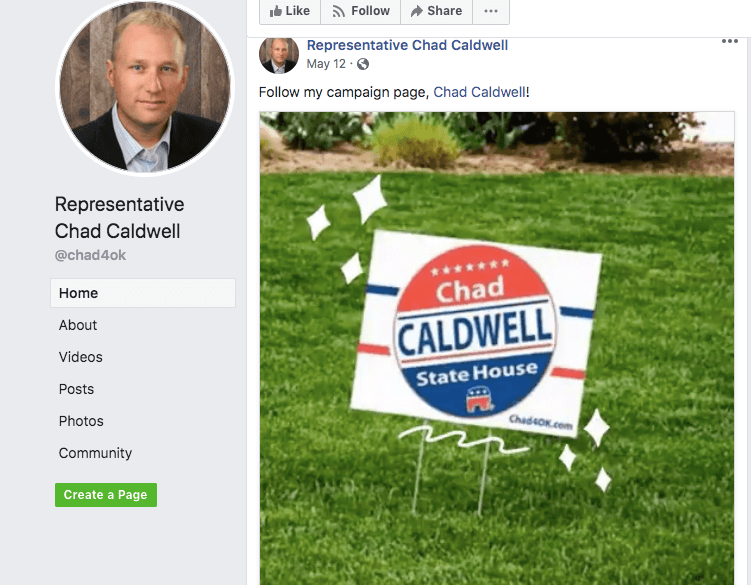

Another relevant case is that of Rep. Chad Caldwell (R-Enid). Caldwell has two accounts, as is suggested by the rules, but he has used his official page, which describes him as a politician, both to advocate for his reelection and direct voters to his campaign page, two actions explicitly prohibited in the Ethics code.

Beyond these examples, a litany of incumbents, including Rep. Monroe Nichols (D-Tulsa), Rep. Chris Kannady (R-OKC), and Sen. Micheal Bergstrom (R-Adair) all run accounts that can’t be easily sorted into any one category or have shared information advocating for reelection on a seemingly official page.

It doesn’t have to be this way

This confusion around social media account usage exists across chambers and parties, and apparent violations may not be intentional. It’s a common problem that a number of governments have had to face in recent years.

In New York City, Newark and Chicago, for example, mayors maintain both official and personal accounts. Proposals have been circulated in other cities to set up official pages for each officeholder, to be maintained by the official’s office no matter who is in office so that any account the officeholder maintains themselves is by default a non-official account.

Most candidates at the federal level follow a model with accounts clearly labeled, and official U.S. House rules prohibit the use of official accounts for any campaign purposes. For the Oklahoma Legislature, even a simple rule from the Ethics Commission requiring a certain style of labeling accounts could prevent confusion.

As long as a significant portion of campaigning occurs online, incumbents will have to figure out what campaigning while continuing to communicate with their constituents looks like. This question is one not just of strategy but of ethics.