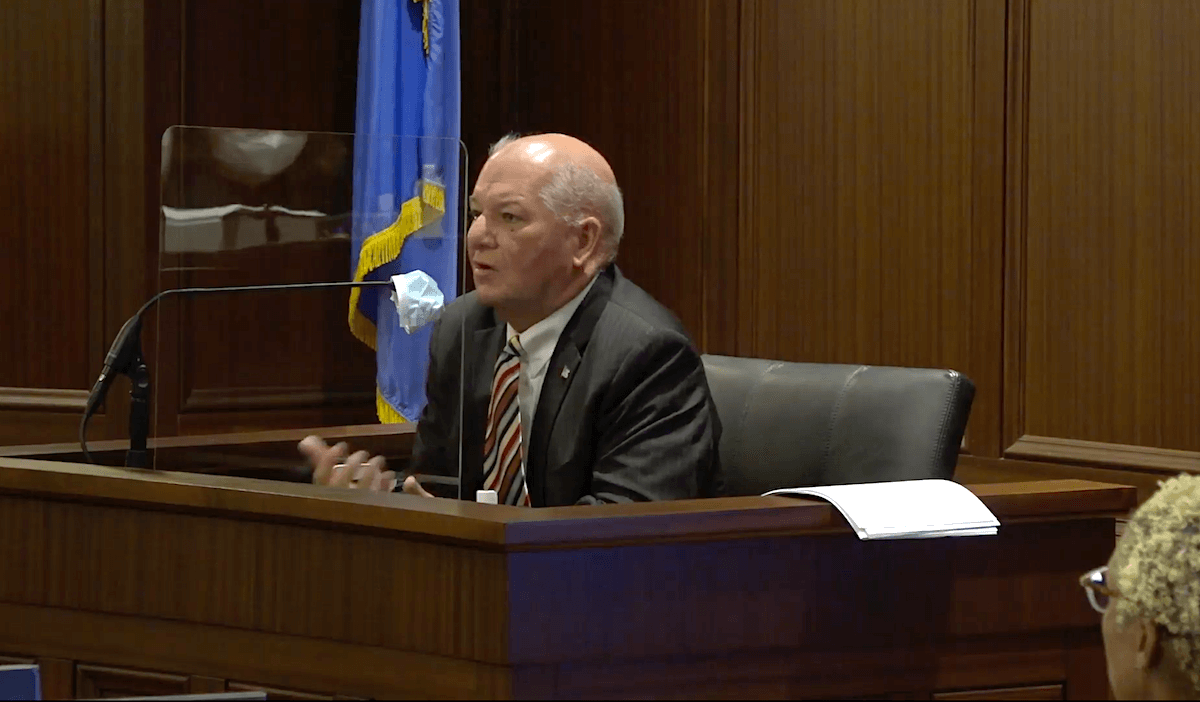

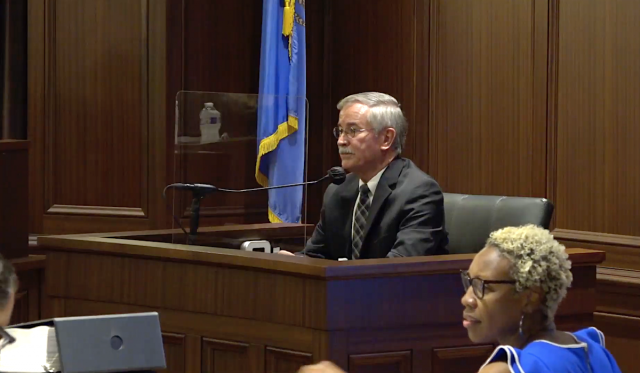

Oklahoma County District Judge Ray Elliott told investigators of the Council on Judicial Complaints that Judge Kendra Coleman exhibited no tendencies of a drug user, but he shared with them a rumor he heard about her associating with a “known drug dealer,” Elliott said Tuesday to the Court on the Judiciary.

Elliott was the prosecution’s first witness to start the second week of Coleman’s removal trial, but his testimony about drug rumors came on cross-examination by Coleman’s lawyer, who contends the Council’s inquiry about drug use demonstrated a racial bias against the first-term district judge. Drug use is not among the charges of judicial misconduct brought by prosecutors against Coleman in the unusual trial before the Court on the Judiciary.

Elliott testified that after his questioning by investigators he asked police about the rumor and they had no information confirming it.

“I inquired of a couple of undercover officers, and they had no knowledge and they had not heard the rumor,” Elliott said. “And so I stopped and let it drop right there.”

The director of the Council on Judicial Complaints testified last week that no evidence of illicit drug use was found by their investigation of Coleman.

The removal trial before the Court on the Judiciary is the most recent chapter in a year-long legal saga for Coleman, beginning with Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater’s attempt to have her recuse from a second degree manslaughter case on May 19, 2019 and then seeking her recusal from all criminal and civil cases involving the DA four months later.

Prater argued that Coleman was biased against the state and that her failure to file state campaign finance disclosures hampered efforts to find bias in favor of defense lawyers who had contributed to her campaign.

The Council on Judicial Complaints contends Coleman violated terms of a probation handed down by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in December when it reprimanded the judge for inadequate campaign finance disclosures to the state Ethics Commission and other allegations of judicial misconduct.

The Council on Judicial Complaints also included as grounds for removal Coleman’s refusal to grant Prater’s blanket request that she recuse from all criminal cases, even though it never questioned Prater about the circumstances and he did not include it in his complaint filed with the Council.

Previous witnesses testified that Coleman expressed belief she was the target of racially-motivated recusal effort by Prater in 2019 — contentions he denied from the witness stand last week.

Prater filed one of the complaints against Coleman that led to disciplinary proceedings that placed her on probation Dec. 3, 2019. She agreed to a voluntary suspension six months later on June 23.

On Tuesday, Coleman’s defense counsel, Joe White, asked Elliott about the alleged drug use topic when Elliott was interviewed by Council on Judicial Complaints investigators last March.

“Do you think, Judge Elliott, that it had anything to do with the fact that Kendra Coleman is an African-American woman, as a district judge in Oklahoma County?” White asked Elliott.

Elliott replied: “That never crossed my mind. No sir.”

Elliott has been a district judge in Oklahoma county for 21 years. He was an assistant district attorney for 19 years before that, serving under DA’s Andy Coats and Bob Macy.

Court closed, briefly

Elliott testified about receiving complaints from lawyers about Coleman’s tardiness at the courthouse. One of those lawyers, David Cheek, also testified on Tuesday, but behind closed doors.

Cheek’s testimony was expected to involve details of a case before the county’s mental health court, the docket to which Elliott — currently the presiding judge — assigned Coleman in January after complaints were received about her handling of guardianship matters.

Such proceedings are confidential, so the Court on the Judiciary trial panel heard Cheek’s testimony with the publicly broadcast live-stream feed turned off. But other witnesses have explained his testimony may involve Coleman’s unavailability to sign a writ of habeas corpus for the release of an individual from a state mental institution.

Elliott said he began receiving complaints about Coleman’s unavailability “from day one” after he assigned her to the victim’s protective order and mental health court dockets. He said those complaints came from victim advocate groups.

Laura McDonald, director of the YWCA victim advocacy program, testified that Coleman refused to allow her and other non-lawyer advocates to stand with victims of domestic violence seeking victim protective orders (VPOs) in her courtroom. She said previous judges had allowed it to be supportive of victims.

“It’s scary for victims of domestic violence and sexual assault to stand in front of the person who has harmed them — the perpetrator — and speak in the courtroom,” McDonald said.

But McDonald said Coleman told her after her first victim protective order docket in January that she was not going to “baby” victims. She also had the advocates remove from the courtroom their literature explaining support for victims.

“She said she wasn’t going to baby anyone in her courtroom. If someone needed a protective order, then they needed to stand up and ask her for it,” McDonald testified.

McDonald said she attended one hearing where Coleman berated a pregnant woman seeking a protective order, stating that “(Coleman) hoped she raised her son not to date women like her.”

‘A follow-up question about rumors’

The courthouse rumor that Coleman had associated with an alleged drug dealer — which Elliott repeated to investigators for the Council on Judicial Complaints last March — took center stage in Tuesday morning’s trial testimony.

“Seems like there was a follow-up question about rumors, and I responded that I had heard a rumor, yes,” Elliott testified, recalling his interview at the Council on Judicial Complaints.

White, who represents Coleman, turned to a copy of the transcript of Elliott’s interview.

“There was no follow up question about a rumor,” White said. “You volunteered the fact that, ‘I heard a friend of mine who goes to every OU-Texas game and has for 20 years and that she saw Judge Coleman and her, quote, boyfriend, at the OU-Texas game this year and that the boyfriend is a known drug dealer. But, other than that, no.’ Do you recall that?”

“I do,” Elliot said.

Elliott testified that during his interview, Taylor Henderson, the director of the Council on Judicial Complaints, asked if he had observed any drug-related behavior of Coleman at the courthouse, believing that Elliott’s judicial and prosecutorial experience might make him familiar with such behavior.

“I believe I can recognize tendencies of various drug users, and I had not seen any such tendencies in Judge Coleman,” Elliott testified.

He said the Council’s board members asked him to inquire further about the rumor, and so he did by asking two undercover police officers he knew. He said he did not remember who it was who told him the rumor.

Elliott said he did not know where the Council got the idea to ask the question. But last week, Henderson testified that Oklahoma City attorney Richard Morrissette described behavior that questioned whether it was a possibility.

Morrisette and attorney Ronald “Skip” Kelly were among the attorneys who filed judicial complaints on Coleman over her handling of guardianship and probate matters. Those complaints were that the judge had berated them and hindered their ability to present their clients’ cases.

Attorney Keith Taggart testified it took three weeks to get a hearing set on a probate matter — a process he says is usually accomplished within a day. When he went to district court administrator Renee Troxell for some help on what to do, he said she referred him to the Council on Judicial Complaints, but he did not file a formal complaint.

Morrisette testified last week that Coleman’s behavior — including rolling her eyes at him in court — was rude and “uncalled for” during a child guardianship hearing in December. He said he did not have any evidence of drug use by Coleman.

Henderson also testified that the Council on Judicial Complaints obtained no evidence from any witnesses interviewed during their investigation of illicit drug use by Coleman.

PREVIOUSLY

David Prater takes stand in day two of judge’s trial by Michael Duncan

One of the complaints against Coleman is that she attended a domestic violence seminar in California on Feb. 10, 11 and 12 without arranging for another judge to cover her cases. Her lawyers have denied those allegations.

Elliott testified that he and Troxell had to “scramble” to find judges available to handle Coleman’s docket during her absence because of the late notice she had provided about her trip.

He said he called Supreme Court Justice Noma Gurich and state Administrator of the Courts Jari Askins whether they had approved the trip and they had not. He said it was customary for the Supreme Court to deny out-of-state travel paid for by the court system owing to a limited budget. However, he said it was not uncommon for judges to pay their own way.

Elliott also testified about a heated telephone conversation with Judge Coleman. Cheek, an attorney, had gone to Elliott about a writ of habeas corpus needing the judge’s signature when Coleman was not at the courthouse. Elliott said he thought Coleman was out of the office but later learned she was at the mental health docket, which is conducted at the Oklahoma City Crisis Intervention Center instead of the county courthouse..

Elliott said after the phone call Coleman sent him an email “basically wanting to know why I was interfering with her docket and why I yelled at her,” Elliott testified.

Coleman’s email was introduced into evidence on Tuesday. It read, in part:

I found it very difficult to understand what you needed from me while you were yelling and speaking over me, demanding to know my whereabouts as my ‘presiding judge’, as you put it.

Elliot said he was merely acting as the presiding judge to assist a lawyer getting a signature.

“I tend to speak very loudly, and so a lot of people think I am raising my voice. But that’s my normal tone,” he said.

Late Tuesday, Assistant District Attorney Jeff Massey, who handles mental health court cases, testified that Coleman appeared to take her responsibilities at the mental health court seriously and there were no issues with her timely attendance from January until she took voluntary suspension due to the disciplinary proceedings against her June 23.

‘This was very unusual’

Much of last week’s testimony concerned charges that Coleman failed to timely file campaign finance disclosures with the Oklahoma Ethics Commission. Attorney Geoffrey Long testified he had helped Coleman get up to date on her financial disclosures.

Long said all pertinent documents and reports had been provided to the Ethics Commission and any incomplete reports had been amended after he conducted a “campaign audit” that reconciled Coleman’s campaign spending with bank account records.

He said he helps candidates for public office navigate the disclosure requirements, which are made via an online system. He said Coleman was not well versed in the system and had difficulty getting it to work during and after her 2018 election campaign. In one instance, she complained that the online system was down.

Long testified that he was responding to the Ethics Commission’s request for the campaign’s financial records in December 2019 — asking the commission to better explain what was needed and why — when the situation deteriorated and the commission held Coleman in contempt.

“I’ve never in my life even heard of the Ethics Commission holding anybody in contempt,” Long said. “This was very unusual.”

Long was legal counsel for the Ethics Commission from 2014 to 2017.

Long’s testimony also dealt with allegations that Coleman improperly spent campaign funds on personal expenditures. Some items focused on by prosecutors were restaurant bills, services of a professional makeup artist and $96 to a local spa on Election Day.

Long said campaigns often have legitimate expenditures for meals of campaign staff and volunteers. He said the makeup was necessary for preparation by Coleman for a photo shoot for campaign literature and the spa was arguably a legitimate expense to prepare her for an Election Night watch party.