Embattled Oklahoma County District Judge Kendra Coleman testified Wednesday that all her campaign finance disclosures to the state Ethics Commission are current and she is making payments on back taxes owed under an agreement with the Tax Commission, despite a pending charge for tax evasion filed against her by District Attorney David Prater.

While answering questions from her attorney, Coleman fought back tears and was granted a 10-minute recess during her ouster trial Wednesday before the Court on the Judiciary, the latest round of legal proceedings involving the first-term district court judge. The trial was set in motion by Prater’s attempt in September 2019 to recuse her from all criminal cases in Oklahoma County. A judicial complaint filed by Prater over tardy ethics reports followed, as well as an investigation by the Council on Judicial Complaints and a reprimand from the state Supreme Court.

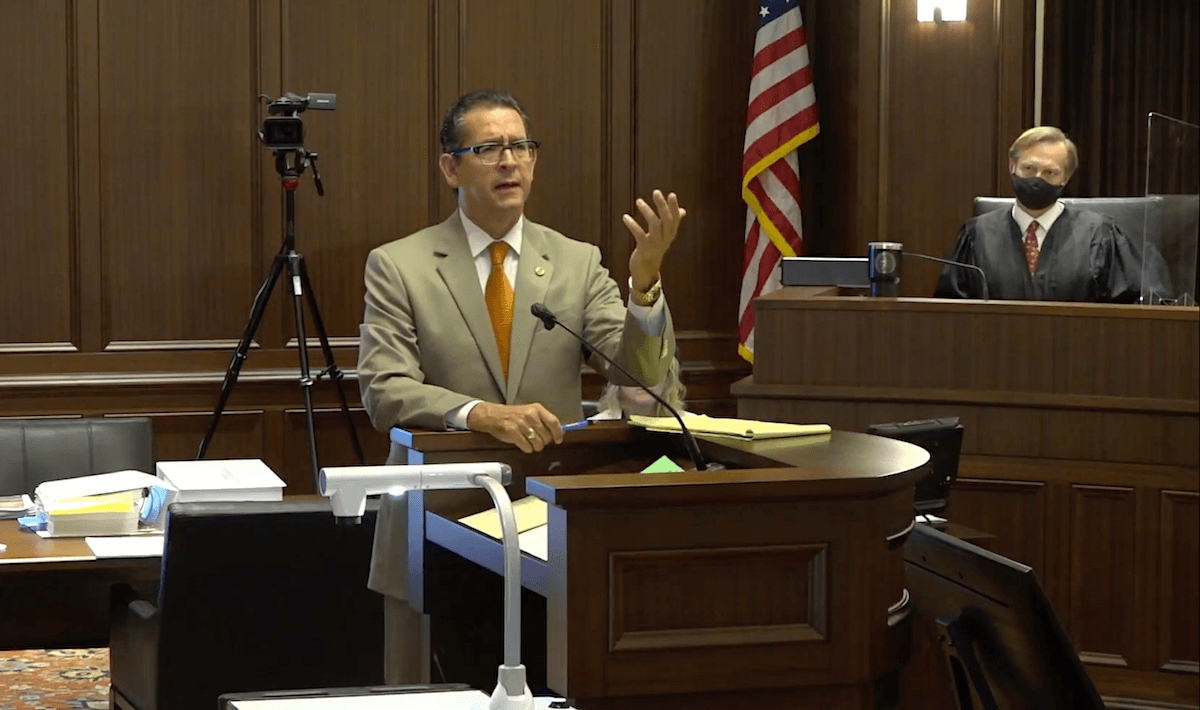

Coleman’s lawyer, Joe White, said Prater obtained a “false indictment” by the multi-county grand jury in September on four misdemeanor tax charges, even though for three years her income tax returns had been filed. White said her returns had only been late for one year.

Coleman’s testimony will continue Thursday morning and will be livestreamed on OSCN.net. Her trial began Aug. 31 and may conclude this week.

‘He’s just as wrong as he can be’

Much of the testimony in recent days has pertained to allegations that Coleman’s treatment of litigants in her courtroom was verbally abusive, charges that Coleman denied.

But focus of the trial shifted back to Prater on Tuesday when The Rev. John A. Reed, Jr., a key leader of the civil rights movement of the 1960s in Oklahoma City, testified that he observed Prater attempting to manipulate Coleman during the Sept. 19, 2019, hearing in which Prater sought a blanket recusal to prevent the judge from handling all criminal cases.

“I noticed the DA and really what he was trying to do and trying to say and trying to manipulate her in the courtroom,” Reed said. “I saw all of that. I saw his anger and all that. He had become completely angry because he could not manipulate this young African-American woman.”

Reed said he had been a supporter of Prater, but he believed the DA was unfair to the first-term judge because he could not control her.

“This particular time, he’s just as wrong as he can be,” Reed said.

He said it was important that the predominantly Black community of northeast Oklahoma County be represented among the corps of judges at the courthouse. Coleman is one of the district judges elected from a specific geographical area of the county that includes most of eastern Oklahoma County.

“This young lady represents that community,” Reed said. “She’s honest, she has integrity. She’s well prepared to represent us. The next thing about it is she has great character.”

He said Coleman continues to have overwhelming support in that community, despite the publicity surrounding the ouster proceeding.

“She’s a blessing to the community right now,” he said.

A pre-judged motion?

Coleman testified Wednesday that the 2019 hearing Reed referenced was when she first learned Prater had obtained a draft response she had prepared to the DA’s recusal motion and left on her desk in chambers.

Earlier in the removal trial, District Judge Cindy Truong testified that she received from court clerk employee Tyler Lambert a cell phone photograph of the draft document on Coleman’s desk without Coleman’s knowledge or permission.

Truong said she sent it to Prater, who then confronted Coleman with it at the hearing, arguing that it was evidence she had committed misconduct by pre-judging his motion before the hearing.

But Coleman testified she had discussed her draft response to Prater’s recusal motion with then-presiding District Court Judge Tom Prince, who suggested she not officially file it. She said she followed his advice and did not file the pleading.

“He suggested I should not file a response, but I should just use that as a template — for lack of a better term — for my order at the hearing,” Coleman said. “I had talked to Judge Truong about it. That’s when I thought we were still friends. (…) Never had I given anyone (the document) or passed out copies or anything like that. I never intended for anyone to have a copy of it except me.”

Coleman testified that her oral ruling denying Prater’s motion at the Sept. 19, 2019, hearing only partly tracked the draft response. She said she was surprised anyone had taken the document from her private chambers and that Lambert was soon transferred from her office.

Before that hearing, Coleman and Prater had met for two closed door conferences in the judge’s chambers when the district attorney made the unusual request that she recuse from all criminal cases because he believed she was biased against prosecutors. The in camera hearings were required by court rules before the public hearing Sept. 19 could occur.

Recordings of the in camera conferences in the judge’s chambers were played during the removal trial. They showed Prater pressing Coleman to tell him about her campaign finance disclosures, but she refused to discuss them. Prater did not reveal to Coleman that he had already filed a judicial complaint against her.

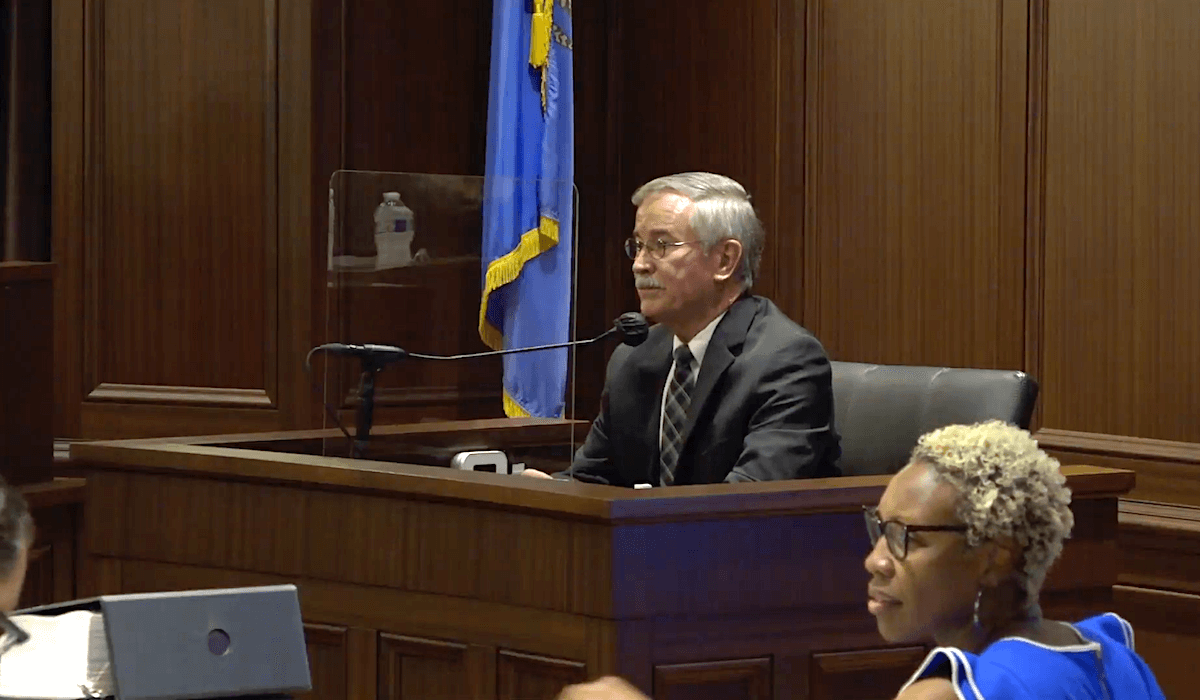

On Tuesday, District Judge Kenneth Watson, who served two terms in office before returning to private practice in 2016, testified for Coleman.

Watson said that when he was on the bench, he had a disagreement with Prater over the DA’s attempt to remove Black jurors from serving on criminal trial juries. Prosecutors and defense counsel must show a race-neutral reason to challenge potential jurors. Watson said he disagreed with how Prater was handling the matter.

“I wouldn’t let (prosecutors) collectively put Black people off a jury just because they were Black,” Watson said.

Watson was among several witnesses who have testified this week in support of Coleman, and he refuted allegations she had mistreated persons appearing in her courtroom.

After Watson returned to private practice in 2018, he appeared as a lawyer arguing cases before Coleman. He said he found her soft spoken, but a stickler for the rules of procedure.

“I didn’t see anything out of the ordinary,” he said. “She was a judge just like all the rest of the judges with their own particular way of doing things.”

‘He wouldn’t let her speak’

During its recent proceedings, the Court on the Judiciary trial panel has heard testimony from two witnesses with the proceeding closed to the public and the live-stream video stopped. Attorney Virginia Laakman and Kandace Williams both gave testimony regarding confidential guardianship proceedings involving Coleman.

However, before Williams’ testimony was closed to the public, she testified about seeking guardianship of a child in a hearing before Judge Coleman and that Richard Morrissette, the attorney opposing her request, was combative with Coleman.

“He wouldn’t let her speak. He constantly interrupted her,” Williams said. “He would constantly speak and not let anyone else speak. He was constantly questioning her comments, her decisions. He (Morrisette) gave a stare-down to the judge like he was challenging her non verbally. It was pretty embarrassing and pretty awful.”

Morrisette was a witness for the prosecution who testified that Coleman’s courtroom demeanor was inappropriate. He filed one of the judicial complaints made against her.

Charlene Metz-Jack, an employee of the Oklahoma State Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services, who worked in support of the mental health court proceedings at the Oklahoma Crisis Recovery Unit, said Coleman presided over the mental health court with compassion.

“She was careful and patient and gave them time to talk if they needed to,” Metz-Jack said. “She did her job like she was supposed to. She was like any other judge would be on her docket.”

RELATED

Read previous coverage of the Kendra Coleman removal trial by Michael Duncan

Criminal defense attorney Michael Johnson testified that Coleman was professional in the courtroom. He said she was among four newly elected judges assigned to criminal cases, so attorneys were learning about each one’s particular courtroom rules. He said Coleman announced her rules before any hearings started.

Karen Colbert, a deputy court clerk who had worked temporarily in Coleman’s courtroom for a week, said she observed some lawyers attempting to undermine Coleman when she took over the guardianship docket.

“She always had to prove that she knew what she was doing,” Colbert said.

Kaye Mullendore, who retired in June from her job as clerk for judges and had previously assisted Judge Richard Kirby, said some lawyers were spoiled, and when Coleman took over the guardianship docket, they balked at changes she brought to courtroom procedures.

“They would try, ‘Well, Judge Kirby did it this way,’ Mullendore recalled. “And she would say, ‘I’m not Judge Kirby, and we’ll do it my way.”

Criminal defense lawyer Nkem House testified that Coleman’s judicial temperament was appropriate, even though she was under scrutiny over Prater’s attempt to remove her from all criminal cases and the subsequent investigation by the Council on Judicial Complaints.

“Even under the circumstances, I never felt like there was anything inadequate about her in my presence, “ House said. “I’ve been doing this for 14 years. I’ve seen the meanest, and I’ve seen the nicest. She wasn’t the nicest and wasn’t the meanest. She was somewhere in the middle.”

‘I thought I had an understanding’

Coleman testified Wednesday she had a misunderstanding on how to do the online report the Ethics Commission required, although she had spoken with the commission’s staff about the reporting requirements beginning in 2016 when she chose to make her first candidacy for public office.

Coleman testified that she converted cash contributions received by the campaign to money orders to create a record of the transactions for reporting purposes. However, ethics rules do not allow cash contributions above $50 to political campaigns.

Wednesday morning, White presented Ethics Commission memos regarding Coleman’s inquiries in 2017 with commission staff.

One issue Coleman said she learned later that had confused her was the requirement to reconcile all expenditures and contributions in the reports, which did not become evident until her last report was filed after the election.

“I then realized in 2019 that I had been doing it wrong the entirety of the time. I thought I had an understanding,” Coleman said.

She said she was able to account for every penny received and spent by her campaign, but it became necessary to have more expertise in making the disclosure reports, so she hired former Ethics Commission lawyer Geoffrey Long to help.

Long was a witness in the removal trial last week. He testified that Coleman had been tripped up by the complexity of the commission’s website and the disclosure requirements, but he found no intent on Coleman’s part to hide anything.

Earlier Wednesday, Oklahoma City accountant John P. Ogilbee testified he began helping Coleman with her tax issues in November and negotiated a payment plan earlier this year toward resolving a $17,616.39 state tax liability. He said Coleman has made timely monthly payments, beginning in April.

Ogilbee said his effort to work out a similar payment plan to resolve a $100,683 federal tax and penalty liability is on hold because the IRS delayed operations during the coronavirus pandemic.