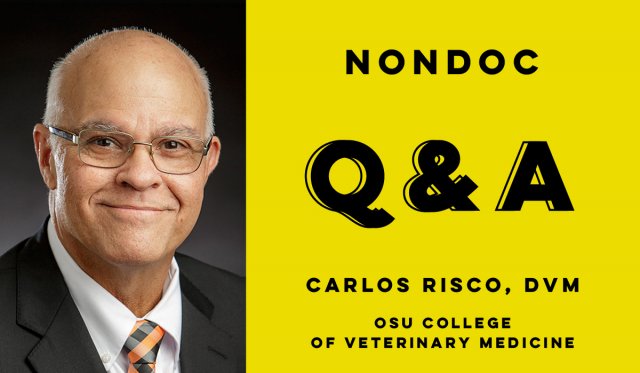

When Dr. Carlos Risco became dean of the OSU College of Veterinary Medicine, in early 2018, he moved to Stillwater after more than 25 years as a faculty member at the University of Florida.

Oklahoma is Risco’s latest stop in a life full of travels. Born in Cuba, he has also lived in Florida, Puerto Rico, Ohio and California. He earned his doctoral degree in veterinary medicine from the University of Florida, and his official OSU biography notes his expertise as large animal medicine and theriogenology, which is a branch of animal science focused on reproduction.

The following Q&A with Dr. Carlos Risco has been edited lightly for style, grammar and clarity.

Please tell us a little about your background. Where did you grow up, how did you become interested in veterinary medicine, and when did you arrive at OSU?

During my childhood, I lived in various towns in and outside the United States, but I call Tampa Bay, Florida, home. I was born in Camaguey, Cuba, and emigrated to the U.S. when I was six years old and lived for about nine months in Miami. My family then moved to Arecibo, Puerto Rico, and from the time that I was 10 years old, I shadowed as much as possible Dr. Juan Gomez, a USDA veterinarian who worked on milk quality, tuberculosis and brucellosis eradication programs in dairy herds.

In my early teens, my family moved to a small farm in Trotwood, Ohio, where I had horses, cattle and raised rabbits that I showed in 4-H. I was also a member of the local Future Farmers of America chapter. My involvement in 4-H and FFA allowed for personal growth and developing an appreciation and interest in livestock production and agriculture. In the 10th grade, I moved to St. Petersburg, Florida, to finish high school. Although I lived in an urban setting, because of my interest in veterinary medicine and livestock production, I joined the Florida Cattlemen Association and recall reading regularly their articles in the “Vet’s Corner” on cattle-health-related topics. I also had an opportunity to volunteer in a small-animal practice with our family veterinarian. My father, who was a physician, played a pivotal role in nurturing my interest in medicine and teaching me the value of an education.

Because of these experiences, I was certain that I wanted to become a veterinarian. After graduation from high school, I matriculated at the University of Florida as a pre-vet student and majored in Animal Science. In 1976, I was admitted to the charter class of the newly formed College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Florida and received my DVM degree in 1980. After graduation, I was in a private dairy practice in southern California for 10 years.

In 1990, I returned to the University of Florida as an assistant professor in a tenure track. I was promoted to professor with tenure in 2002 and became chairman of the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences in 2012. In March 2018, I joined Oklahoma State University, where I serve as dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Only 30 accredited veterinary colleges exist in the U.S. What makes OSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine special?

There are many reasons why I was attracted to OSU that make it a special college of veterinary medicine. The program was built on a culture of scholarship, which has led to the excellent reputation of training practice-ready veterinarians.

This reputation makes Oklahoma State a place students want to attend, as does our multidisciplinary approach to improve both animal and human health. We also enable collaborative research between the college and other departments across the university to advance research relevant to veterinary medicine. We work to improve the health of the diverse animal industries in the state through the Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, and we try to address the needs of rural communities by providing outreach to the agricultural and veterinary communities. We value the opportunity to train future academic veterinarians through the college-based comparative biomedical sciences graduate program and joint degree options, and the Boren Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital allows our students and house officers to develop the science and skills needed to practice quality medicine.

Lastly, we have a community of faculty, staff and students that promotes a learning environment of inclusion and respect to all. These attributes provide an ideal framework to continue progress in the college’s vision to become innovative world leaders in health care, research and professional education.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (OADDL) within your college quickly went through a transition and became the state’s leading lab for processing COVID-19 tests. That ended in late September, but what were the challenges along the way?

The most challenging part for OADDL to become the leading lab in the state to process COVID–19 tests early in the pandemic was to provide human testing while continuing to offer full-service animal diagnostic testing. This was a tremendous challenge for a lab with just 25 people! It was also challenging to hire and train the additional personnel needed to sustain the testing effort, with 24 to 48-hour turn around times expected for results. Many employees had to work long days. In the beginning, energy was high and personnel were eager to assist with this crisis. As time went on and there appeared to be no end in sight, it became difficult to sustain with the limited personnel we had. The lab also faced IT challenges and needed to modify our software so emails could be sent in an encrypted form required by HIPPA regulations.

The OSU College of Veterinary Medicine operates a 24-hour emergency hospital that treats a variety of animals and provides learning opportunities for vet students. Describe that effort’s impact on Oklahoma.

RELATED

Overnight at the OSU Veterinary Medical Hospital by Heide Brandes

A major impact of our hospital is that it provides clinical instruction to students who, after graduation, will practice quality veterinary medicine in Oklahoma and contribute substantially in various ways to their communities. Through its specialty services by board-certified veterinarians, the hospital provides quality veterinary care to small, large and exotic animals. The hospital also serves as a vital referral center to practicing veterinarians in Oklahoma.

Our shelter medicine program provides student-centered surgical services for various animal shelters in Oklahoma. Clinical rotations during the senior year include not only the departments within the hospital, but also opportunities at the OKC and Tulsa zoos. The hospital also provides training to interns and residents to become highly skilled board-certified specialists.

Our hospital reaches its goals to educate tomorrow’s veterinarians thanks to faculty members who serve as role models, clients who allow the additional time it takes to teach students in the moment, and veterinarians who refer their patients for specialized treatment.

With the relocation of the Oklahoma state public health laboratory to Stillwater as part of the Oklahoma Pandemic Center for Innovation and Excellence, what opportunities do you see for your college and for the state as a whole? What do people not understand about the relationships between animal health and human health?

The Oklahoma Pandemic Center for Innovation and Excellence (OPCIE) was formed to study and address pandemics and is linked to public health and the move of the public health lab. The OPCIE intends to become a leading authority on all aspects of human and animal health and agriculture to improve our state’s public health preparedness and response. The OPCIE will administratively include Oklahoma State University, the University of Oklahoma, the OSU College of Veterinary Medicine and numerous other public and private partners.

Our college is excited to partner with the OPCIE and contribute to the mission of the center to advance public health in research, service and training. The CVM has a wide range of expertise in public health, disease diagnostics, microbiology, virology, parasitology, toxicology and clinical and anatomic pathology. We have experience with a range of pathogens — including respiratory viruses — regarding isolation, cultivation, model systems and pathology. We have research capability in genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic analysis, bioinformatics, host-pathogen interactions and immunology. We are certified to work with pathogens in BSL-3 containment in vitro and in animal systems.

Several OSU research groups interested in respiratory diseases and viral diseases, including the statewide network of researchers affiliated with the Oklahoma Center for Respiratory and Infectious Disease (OCRID), are moving to put their expertise to work on the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. Genomic analysis and both in vitro and in vivo analysis of the virus and the pathogenesis of COVID-19 are underway or planned. Proposed expansion of infectious-disease research in the context of the OPCIE promises additional opportunities.

In addition to morbidity and mortality resulting directly from infection with SARS-CoV-2, there are numerous co-morbidities that impact outcomes of COVID-19, including hypertension, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, lung disease and age. Multiple scientists at OSU and around the state are already doing research on these co-morbidities and can make contributions to understanding the role they play in health outcomes for patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory can develop and validate assays for zoonotic disease agents such as influenza, West Nile virus and rabies, to name a few. OADDL can provide complementary testing and referral lab support in rabies testing currently conducted at the public health lab. In view of the wide variety of laboratory techniques conducted at OADDL under a stringent quality-management system, the lab could help train OPCIE personnel in laboratory techniques.

The current pandemic has taught us a hard lesson of the critical role that public health has on the wellbeing of our society globally. What I would like everyone to understand about the relationships between animal health and human health is that they are inextricably linked to public health. In recent years, this link with the inclusion of environmental health has been referred to as “one health.” The term “one health” encompasses more than zoonosis, or diseases transmitted from animals to humans. Although not new, as veterinarians have been practicing one health for years, the term as defined by the CDC refers to a transdisciplinary approach with the goal of optimal health outcomes, recognizing the interconnection between people, animals and their shared environment. I cannot think of a better example for one health than the COVID–19 pandemic, with the transmission of the virus originating in bats or pangolins with subsequent transmission to humans, and the work led by OADDL veterinarians to test for the virus in people.

What might most people not realize about their local veterinarian?

The local veterinarian in a rural or urban setting is a highly trained, skilled, health professional capable of solving societal needs beyond treating pets and large animals. They promote the value that pets bring to the human-animal bond. They work with farmers and ranchers to provide a wholesome and economical source of food animal protein. They mitigate the spread of zoonotic diseases that affect public health. Working with state and federal agencies, they deter the entrance of foreign animal diseases to the U.S. which could be catastrophic to our livestock industry. They work with local animal shelters to reduce the number of unwanted dogs and cats by encouraging responsible pet ownership that includes spaying and neutering.

Every veterinarian has an amusing story about an unusual interaction with a patient. What is your favorite or most interesting memory about treating an animal?

My most unusual and reverent case was a difficult birth or dystocia in an African elephant cow at Disney’s Animal Kingdom, in Orlando, Florida. After examining the animal, I determined that the dystocia was due to uterine inertia that resulted in the calf’s death by not allowing for a natural birth. My challenge was to recognize the anatomical features of the elephant cow that are different from the other type of cows that I am familiar with. However, after applying the guidelines to determine if vaginal delivery is possible in cattle, I proceeded and successfully delivered the deceased elephant calf. I felt much joy that I was able to provide relief to the dam despite the delivery of a dead calf, and for the unique opportunity to work with this magnificent animal.