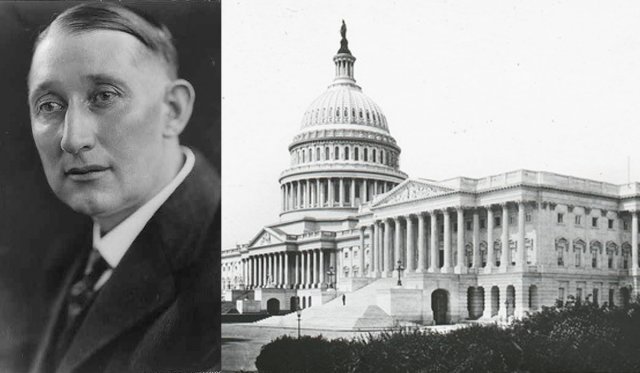

Manuel Herrick (1876-1952) represented Oklahoma in Congress for a single term, which, in the minds of some, was one term too many. But it was not his brief political career that made him memorable.

Herrick’s mother was a bit odd. Well, that is the charitable way to describe her. The woman had a couple of significant screws loose.

She called her son Immanuel and told him he was Jesus. His father, an illiterate, went along with it, so Manuel grew up believing he was Christ and that his birth was the second coming. Both parents always walked behind him, as one might expect to behave around Jesus.

Herrick tried to parlay his holy status into a pastorate, but congregations were unwilling to acquire his services (so to speak). Eventually, after failing to find a church that would have him, Herrick decided to abandon the pulpit and go for the stump. He entered politics.

Politics, as usual

Alas, in addition to his Jesus claim, Herrick hauled other baggage that the electorate found disqualifying. At age 17, he had tried robbing a train. (None of that rendering unto Caesar stuff, one supposes.) He harassed his family’s neighbors more or less continually, and his track record led to a room in a mental institution. Upon release, it was politics as usual.

Perhaps Herrick drew inspiration from the example of Al Jennings, a former outlaw who ran for governor of Oklahoma in 1914 and came in third. But Jennings had received a presidential pardon in 1907 and made no claim of being Jesus.

Herrick ran for assorted local positions and always lost. Then World War I ended, and Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s popularity had waned. There was widespread displeasure with Wilson’s Fourteen Points and the idea of a League of Nations, but beyond that, there was popular support for higher tariffs and, of course, lower taxes. By 1920, the country was ready for what Republican Warren G. Harding would call a return to “normalcy,” by which he meant normality.

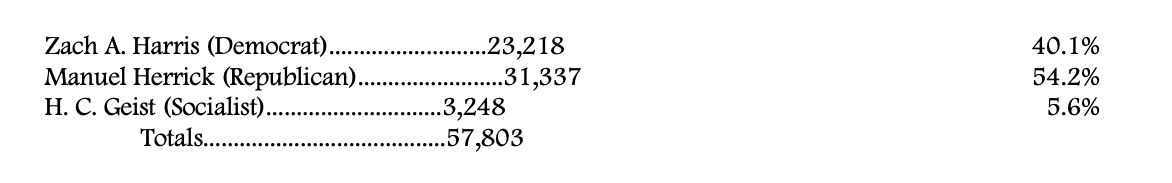

Oklahoma’s 8th Congressional District had a Republican representative named Dick T. Morgan, up for re-election in 1920. Manuel Herrick was the only person who filed to run against him as a Republican. Unhappily for the reputation of the Sooner State, Morgan died on the last day to register for the GOP primary, and Herrick won the subsequent down-ticket general election as Republicans swept the field.

All that glitters is not gold

The best thing about Herrick’s two years in Congress was his friend and speech-writer, Harry B. Gilstrap, who also screened visitors when they wanted to have a word with Jesus. Aside from the few serious things Herrick did, such as advocating military air power for America, rather than naval investment, he may be best remembered for his campaign against beauty contests. Herrick thought such events led young women astray, which is to say away from home.

To prove his point, he staged a beauty contest of his own, promising the winner the hand of a wealthy young man in marriage. The man, of course, was Herrick himself. When a woman who claimed to have won the contest refused to marry him, Herrick sued her for breach of promise. He won the case, and the judge awarded him the munificent sum of $0.01.

RELATED

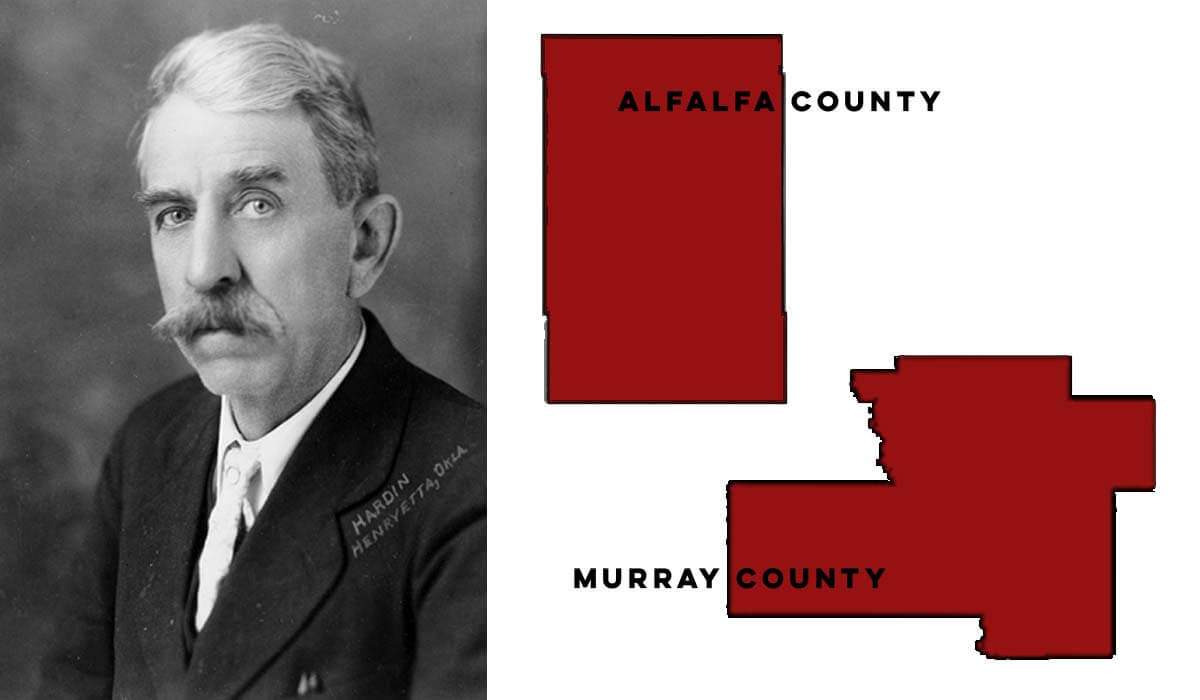

History is clear: Alfalfa Bill Murray was a terrible bigot by William W. Savage Jr.

Ridicule directed at Oklahoma for sending such a person to Congress contributed mightily to Herrick’s defeat in 1922 when he finished third in the Republican primary with 19 percent of the vote. Over the next decade, he ran every two years, trying to regain his seat. He was spectacularly unsuccessful.

In 1933, arguably the worst year of the Great Depression, Herrick took his political hat out of the ring and moved to northern California to search for gold. Fifteen years after that, he could not resist running for Congress from the Golden State, but he lost yet another election.

Herrick died in a snowstorm in January 1952. He was showing another man his gold mining claim, and both were caught in the blizzard. Herrick’s body was found under a couple of feet of snow. He was cremated, and his ashes remain in California, the state later dubbed “the last place you come to” by historians seeking to explain the assorted migrations westward in the 19th and 20th centuries: gold rush, Hollywood, rock and roll, and so forth. For Manuel Herrick, it was indeed the last place.

(Because your editor does not appreciate my brevity, sometimes known as economy of language, I shall fatten this piece by adding that the book to read, if one wishes to slog through Herrick’s speeches or the details of his beauty contest and subsequent litigation, is The Okie Jesus Congressman by Gene Aldrich, published in Oklahoma City in 1974. Amen.)