On June 3, beneath the illuminated OKLAHOMA sign that hangs above the stage upstairs at Ponyboy in Oklahoma City, the bar’s co-owner Chad Whitehead took the mic and welcomed a crowd full of young, hungry musicians to the first ever Load Inn. Roughly 15 months had passed since the COVID pandemic had forced Whitehead to shut down the bar and the historic and beloved Tower Theatre next door, which he also co-owns. Now, finally, as an Oklahoma-centric playlist blared and friends reunited after extended social distancing, Whitehead felt cautious optimism.

Whitehead’s hope is to make the Load Inn a monthly music-industry get-together, a chance for those in the scene to rub elbows and make connections. But, that first night, it was an emotional declaration that the OKC music community was back from its momentum-shattering, pandemic-imposed hiatus. The excitement was palpable, as ecstatic reunions faded into drinking and dancing — a pulsing, rhythmic exorcism of the quarantine demons. Something was finally happening again.

Soon, these artists will be taking the city’s stages by storm, cranking up the volume, and performing almost as if nothing ever happened. But first, the venues they perform in have had to get back up and running. And for that to happen, they’ve had to navigate a maze of competitive grant applications, booking requests and, of course, health and safety concerns. With no clear answers on how to handle the situation, owners, managers, bookers and a new trade association are exploring all options in an effort to bring the music back to OKC.

‘Busy once again’

Last year, in the thick of the pandemic, bars and venues across the country struggled with questions of when and how to reopen. Some, like the Tower Theatre, attempted the occasional, strictly regulated event. Others, such as OKC hard-rock hotspot Blue Note (just down the street from the Tower), tried to juggle the various mask mandates, capacity limits and distancing measures while still hosting any acts that wanted the stage.

Most of the state’s venues just stayed dark.

Since Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt effectively lifted every remaining restriction this spring, that tightrope walk is finally ending, and venues are holding their first full-capacity events in well over a year. Whitehead is particularly excited about what this means for returning artists.

“Bands lost a lot of what they had been building,” Whitehead said. “The momentum that was lost as artists was very significant, and they’re still trying to figure out how to recover.”

That desire of artists to pick up where they left off has created the first and possibly most daunting issue facing the resurgent music industry: a monumental number of booking requests.

“Booking has become much more intense in the last few weeks,” said Jon Jackson, booking manager for the Blue Note. “Bands are requesting at an alarming rate, and we’re mostly booked solid about seven months out at this point.”

The crunch is compounded by the fact that some venues are still choosing caution over crowds.

One of those is The Study, a wine bar and creative space on OKC’s Film Row that had the misfortune of opening in March 2020. Elaine Hamm, one of the co-owners, who also has a Ph.D. in microbiology, said she has been adamant that the business would adhere to scientific recommendations and not host large gatherings of any kind. Even now, as restrictions have been significantly loosened, she has made the controversial decision to check patrons’ vaccination status at the door before letting them in unmasked. As a result, she is still reluctant to allow concerts and events inside the space.

“Everyone has a different level of safety and comfort,” Hamm said. “I want people there. I want people to enjoy the space as we intended, with music and book clubs and trivia, but you can’t enjoy those things if you are stressed out about getting sick. So we are going to ease into it and make sure what we are doing is right and that we are executing it safely.”

Jackson said he doesn’t believe his approach of booking as many acts as possible stands at odds with safety concerns, given the recent CDC guidelines for people who have been fully vaccinated.

“No one has mentioned that we shouldn’t be currently having shows,” he said. “And with the recent announcements stating fully vaccinated people are encouraged to go back to a normal lifestyle, outside of medical and travel situations, I fully expect the bar to become very busy once again.”

No shows, no work

The sudden increase in patronage is coming at a crucial time, as music venues are scrambling not only to recoup some of the substantial losses over the past year but also simply to pay their employees, many of whom work as contractors and freelancers.

“Our techs work on a show-by-show basis,” Whitehead said. “If there’s no shows, there’s no work, and that was pretty painful.”

The same concern was a significant factor behind the Blue Note’s decision to continue holding shows after initial pandemic restrictions ended.

“Something I needed to consider was that part of my staff had been without work for nearly four months,” Jackson said, “and they were ineligible for unemployment benefits as contractors. With the majority of every business shut down and no one hiring, where were my staff to turn?”

As part of the pandemic relief package signed at the end of 2020, the federal government set aside $16.2 billion for the Shuttered Venues Operator Grant, or SVOG, meant to help owners and staff of entertainment venues across the country. However, this sum is being split not only among members of the live-music industry but also among movie theaters (which lost more than 11 billion dollars lost to the pandemic) and many other branches of the entertainment industry, from talent agencies to zoos. As a result, getting money from the SVOG has become highly competitive.

Approximately 17,000 applications for SVOG money were submitted in the first 24 hours after the fund’s website got up and running, on April 26, and the first payments are only now slowly rolling out, including to the Tower as one of the lucky few. More than 5,000 independent venues nationwide have submitted applications, and fewer than 700 have received money so far. This has left many cash-strapped venue owners looking for help in navigating the bureaucracy.

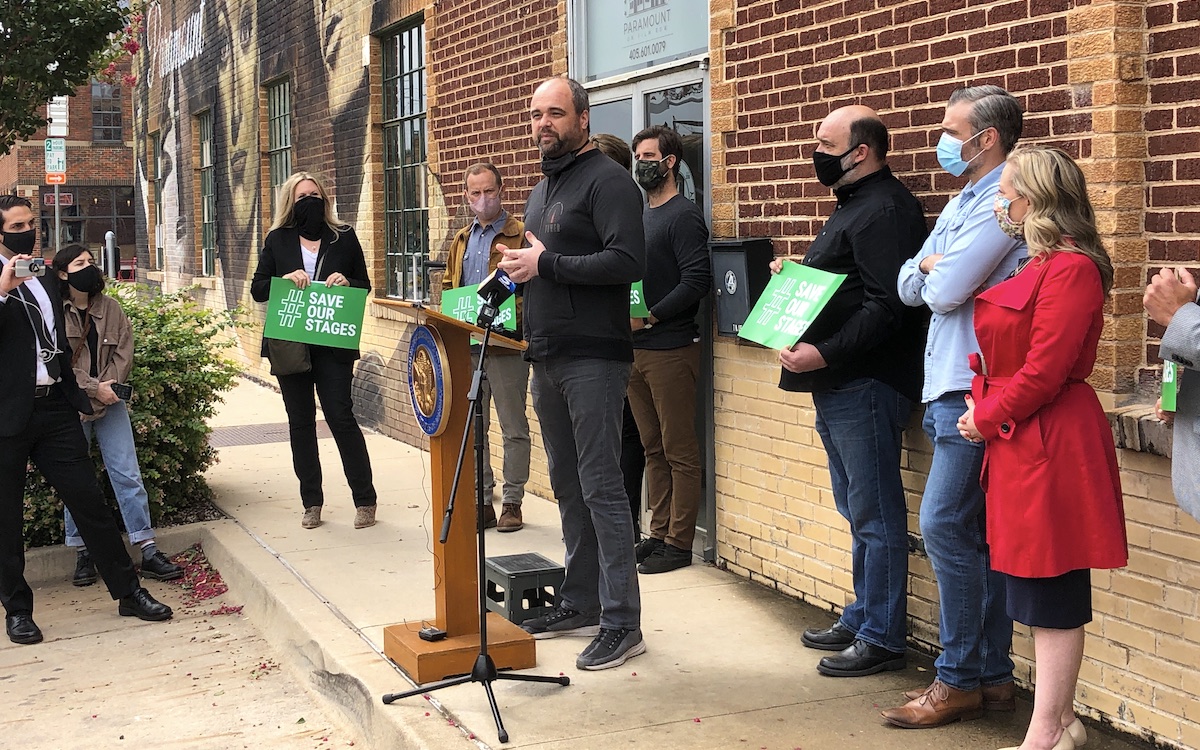

Enter Dustin Green, former Oklahoma House of Representatives staffer and lobbyist, and his new Oklahoma Nightlife Association, a trade organization that helps bars and music venues apply for government grants and aims to push back against a wide range of regulations that affect the industry. Among other things, the organization objects to regulations that singled out entertainment venues during the pandemic.

“I realized there was a need for an association after conversations with close friends who own entertainment venues,” Green explained. “Their businesses and personal political beliefs are polar opposites, yet the complaints they expressed about taxes, licensing, and government mandates were almost verbatim. I suggested they contact their association to introduce legislation and when both said there was no association to call, the light bulb went off.”

The biggest issues facing the entertainment industry, Green said, are financial, as taxes, fees and insurance costs grow. Meanwhile, attendance in some spaces is reaching historic lows, thanks in part to government restrictions on things like capacity and operating hours enacted during the pandemic.

“Most feel that the government sees their businesses as low-hanging fruit to saddle with new fees or tax increases each time there is a revenue shortfall,” Green said. “The government shouldn’t be in the business of choosing winners and losers. By enacting mandates that specifically target bars and nightclubs, that’s what they did, and it has been devastating to business owners across Oklahoma. At the end of the day, people need to be allowed to make the decisions that are best for them and their family.”

According to Green, the association has already worked with a number of important spots in the city, including The Criterion, one of OKC’s largest and highest-profile music spaces.

Some may object to the association’s efforts to keep venues open even in the face of a highly transmittable airborne virus — variants of which are fueling new infection spikes — but Green draws a clear line in the sand, dismissing the closure of entertainment spaces as “political theatrics.”

“We don’t believe one is any more likely to contract a virus in a bar at midnight than they are at a church service at noon or a convenience store at five,” he said. “If the business is complying with all the recommended protocols, then it should be allowed to otherwise operate as usual.

‘Don’t call it a comeback’

So what will “business as usual” look like going forward? How will performance spaces keep the doors open but also keep audiences safe? Will upcoming shows look like the Flaming Lips’ “Space Bubble” concerts?

According to Dr. Hamm, it’s all up in the air.

“Step one is just every space having its own HEPA air purifier with UV sterilizer and trying to find an aerosolized way to disinfect,” she said. “So not just wipes and stuff, but the actual air.”

HEPA filters and proper ventilation are also a top priority for Whitehead and the Tower, especially as the venue prepares to host full-capacity crowds for a series of shows being billed as Don’t Call It a Comeback. The shows, which are slated to run through July and will be free to attend, are intended to calm some concerns and hopefully spread the creative energy that that crackled at the Load Inn.

But Whitehead acknowledges that the future of the industry mostly depends on audience members and whether they get vaccinated.

“We want to be very clear that we think the best way for music to come back is to get vaccinated,” he said.

Hamm agreed, though she makes it clear she feels the reopening efforts have been a bit too gung-ho.

“I hate the way the CDC did this,” she said. “It was a very big change that went into effect immediately. That said, under the lens of what makes sense for vaccinated people, all of the immunology data points to the fact that vaccinated people are protected.”

But with vaccination numbers seemingly stalling statewide and practically all “pandemic era” restrictions loosening, concern is already growing that another serious wave of the virus could sweep the country. If that were to happen, Green and the Oklahoma Nightlife Association have vowed to be on the front lines, lobbying politicians to keep venue lockdowns entirely off the table, putting the onus on the owners and managers themselves to weigh public safety against their and their staff members’ livelihoods.

Whitehead is adamant that, even in such a scenario, the community he loves will do the right thing.

“If things were to go to hell over the summer, I’m very confident that the industry is going to respond appropriately, and that might mean that things push off into 2022 and we do this whole thing again,” he said.

Whitehead then paused and took a breath.

“But I sure hope not.”