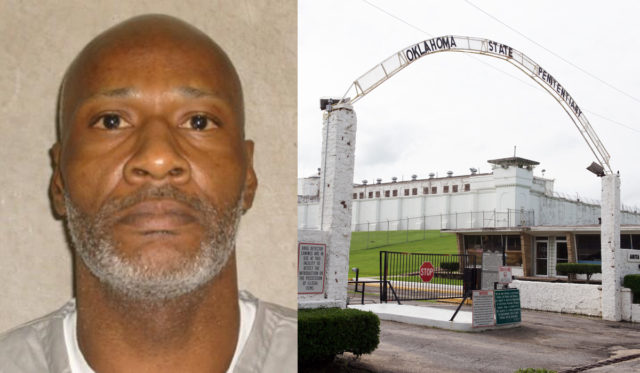

Less than two hours after the U.S. Supreme Court voted 5-3 to vacate a stay of execution for John Marion Grant, officials with the Oklahoma Department of Corrections administered a lethal concoction of drugs that made Grant the first man executed by the state in more than six years.

Grant was convicted of first-degree murder after stabbing Dick Conner Correctional Center kitchen employee Gay Carter more than a dozen times in November 1998. He had been on death row for more than 20 years.

On Wednesday, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals stayed the execution dates of Grant and Julius Jones, ruling that both men should be added again as plaintiffs in a pending lawsuit challenging Oklahoma’s execution process. But the Supreme Court reversed that decision roughly 24 hours later.

Justin Wolf, Oklahoma DOC’s director of communications and government relations, announced the completion of Grant’s execution, which had been scheduled to begin at 4 p.m.

“The sentence of John Marion Grant has been carried out,” Wolf told media gathered at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. “The time of death is 4:21 p.m.”

A handful of media witnesses — selected by random drawing to watch the execution — said Grant yelled expletives, convulsed and vomited on himself during the lethal injection process. Grant was said to have lost consciousness about 4:15 p.m., six minutes before he was pronounced dead.

— Kassie McClung (@KassieMcClung) October 28, 2021

Background on executions in Oklahoma

The state of Oklahoma halted executions following a pair of botched lethal injections in 2014 and 2015. Grant was one of more than 30 death-row prisoners who have challenged the constitutionality of the state resuming executions with the same cocktail of drugs that were authorized for Clayton Lockett and Charles Warner.

In April 2014, Lockett was put to death with the use of a three-drug lethal injection that took 43 minutes and led to Lockett dying by heart attack, a result deemed cruel and inhumane. The drugs used in the execution were midazolam, bromide and potassium chloride. In 2000, Lockett had been convicted of the kidnapping, rape and murder of 19-year-old Stephanie Neiman.

The botched execution of Lockett led to former Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin suspending executions pending an independent review of the process. In May 2014, Oklahoma Department of Corrections chief Robert Patton released a report of the timeline of Lockett’s execution. The report showed that Lockett’s vein had collapsed and that the drugs had “absorbed into tissue, leaked out or both.”

In January 2015, the state resumed executions and performed a lethal injection on Charles Warner, who was convicted in 2003 for the 1997 first-degree rape and murder of his girlfriend’s 11-month old daughter. Following the execution, an autopsy completed by the Oklahoma Office of the Chief Medical Examiner showed that the wrong combination of drugs was used on Warner. Potassium acetate had been used in the injection to stop Warner’s heart rather than potassium chloride.

Grant’s execution was carried out with the same combination of drugs used before the moratorium, but the state had instituted new protocols.

“The additions that we’ve made to the protocol simply add more checks and balances, more safeguards to the system, to ensure that what has happened in the past won’t happen again,” then-Attorney General Mike Hunter said in February.

Oklahoma’s executions are carried out in a chamber within the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Members of the media were selected to witness the execution of John Grant. Storme Jones of News 9 reported that Grant would only have two attorneys in attendance on his behalf.

“The convulsions seemed to be somewhat similar to what I witnessed in the Clayton Lockett execution, although he appeared to be somewhat conscious, Lockett did,” Sean Murphy of the Associated Press said. “[John Grant] did continue to breathe all the way until after the second drug started to flow.”

Daughter of victim interviewed by KFOR

Grant was sentenced to death for attacking Gay Carter after she removed him from a job in the Hominy prison’s kitchen. He stabbed her 16 times with a shank and then stabbed himself several times in the chest before guards could intervene.

Carter was 58 and had worked at the prison since 1991.

At the time of the murder, Grant had been incarcerated since 1980, serving a 35-year sentence for armed robbery.

In his clemency hearing Oct. 5, Grant’s attorneys argued that he had incompetent legal counsel in his trial and that he should be extended mercy based partly on the fact that he grew up in dire poverty and suffered severe abuse as a child. His clemency petition pointed to neglect and abuse Grant suffered in juvenile institutions where he was sent for stealing food and clothing for his siblings.

“The state helped to create a broken man,” the petition said.

The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted 3–2 to deny clemency. Board members Adam Luck and Kelly Doyle voted in favor of clemency. Richard Smothermon, Scott Williams and Larry Morris voted against.

At the hearing, Morris explained the reason for his vote, saying, “It’s my opinion that the hurdles that he has had in his life were high and difficult, but at the same time I have not heard anything from anyone to suggest that he did not know the difference between right and wrong, and for that reason, my vote is ‘no.’”

Grant was sentenced to death in 2000 and was originally scheduled to be executed in Dec. 2014, but the date was pushed back to February 2015 following the botched execution of Lockett. When the state used unapproved drugs in the execution Warner, all executions — including Grant’s — were put on indefinite hold.

On Wednesday evening, KFOR’s Joleen Chaney interviewed Pam Carter, the daughter of Gay Carter, who said she has been on “an emotional rollercoaster” during the various hearings, court challenges and legal decisions related to Grant’s execution.

“Just when you kind of think you’ve got a handle on your emotions, things come back up, and the wound is opened back up,” Carter said in the interview.

Chaney reported that Pam Carter was planning to attend the execution today if the U.S. Supreme Court authorized it to move forward.

“My theory about the death penalty is there are some crimes that are so reprehensible that that is the ultimate option, because it is not about revenge. It is not about revenge. It is about keeping another person safe. I want to make sure that this does not happen to anybody else, that nobody has to go through what I and my family has had to go through,” Pam Carter told KFOR. “The main thing it would have done for me, I think, is so I could say, ‘Mom, he’s not going to hurt anybody else,’ because that’s what this is about, not letting him hurt someone else.”

Opponents of the death penalty, however, view the situation differently.

“Mr. Grant has been in state custody since he was 12 years old,” Rev. Don Heath, chairman of the Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, said in a press release Thursday. “He was severely abused at the juvenile facility and placed in isolation for long periods of time. He never received any services to address the abuse and abandonment he suffered there. Forty-eight years of incarceration in Oklahoma juvenile and penal institutions is enough.”

The firm Cole Hargrave Snodgrass & Associates released polling Thursday morning that said a majority of respondents — 63 percent — support the death penalty, with 23 percent opposing the practice. Pat McFeron, the firm’s president, wrote that the numbers mirrored a similar polling question in 2015 when 68 percent of respondents expressed support and 24 percent expressed opposition.

On social media, some on social media pointed to 2015 data from a separate firm — SoonerPoll — that indicated 52.4 percent of respondents support replacing the death penalty with life without parole and financial restitution.

Earlier Thursday, two candidates for Oklahoma governor in 2022 — Democrat Connie Johnson and Libertarian Natalie Bruno — held a virtual press conference calling on Gov. Kevin Stitt to stop the resumption of executions.

Thursday evening, Stitt released a statement referencing State Question 776, which passed with 66.3 percent support from voters to enshrine the death penalty in the Oklahoma Constitution.

“When I took the oath of office as governor, I swore to support, obey, and defend the laws and Constitution of the State of Oklahoma, including Section 9A of Article 2 which was added in 2016 by the people of Oklahoma. Today, the Department of Corrections carried out the law of the State of Oklahoma and delivered justice to Gay Carter’s family.”

Six other men have scheduled execution dates

The U.S. Supreme Court decision Thursday also vacated the stay of execution for Julius Jones, whose high-profile case and claims of innocence have drawn national attention.

Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor has set execution dates for Jones and five other men:

- Julius Jones, November 18 (Clemency hearing Nov. 1)

- Bigler Stouffer, Dec. 9 (Clemency hearing delayed until further notice)

- Wade Lay, Jan. 6 (Clemency hearing Nov. 17)

- Donald Grant, Jan. 27 (Clemency hearing Nov. 30)

- Gilbert Postell, Feb. 17 (Clemency hearing Dec. 1)

- James Coddington, March 10 (Clemency hearing Jan. 19)

(Editor’s note: Andrea DenHoed, Megan Prather and Archiebald Browne contributed to this report. The story was updated at 4:45 p.m. to include reports from media who witnessed the execution of John Grant. It was updated again at 8:14 p.m. to include Stitt’s statement.)