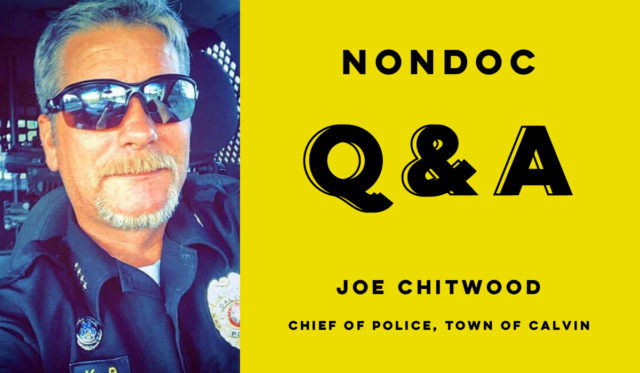

HUGHES COUNTY — Even though he is the only salaried law enforcement officer employed by the southeast Oklahoma town of Calvin, Chief of Police Joe Chitwood does respond to many calls with backup: the K-9 officers he trains and cares for at his home south of Wetumka.

Chitwood grew up in the area, worked for private military security firms overseas during the Iraq War and returned to Hughes County unsure what he would do next for a career. After becoming a certified law enforcement officer, Chitwood eventually became chief of the Wetumka Police Department.

A series of unusual political events led to Chitwood clashing with a man named James Jackson, who had been elected to the Wetumka City Council along with his wife, Rebecca. James Jackson became mayor, and he led the firing of Chitwood after Chitwood had investigated Jackson for allegations of inappropriate behavior involving children. Jackson subsequently fired other Wetumka police chiefs as well before being thwarted in an attempt to abolish the police department altogether.

Months later, the Jacksons resigned from the Wetumka City Council and were subsequently arrested in a joint operation between local and federal law enforcement. James Jackson remains in Hughes County Jail and is awaiting trial on seven criminal charges, including aggravated possession of child pornography, lewd or indecent acts to a child under 16 and beastiality.

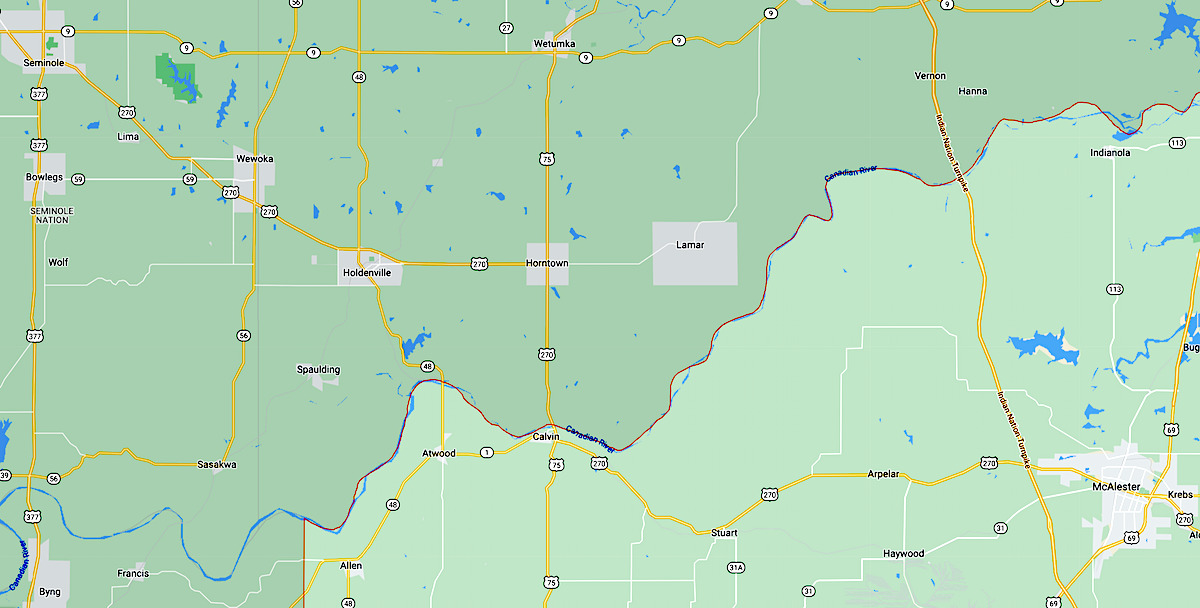

Chitwood has now served as Calvin police chief for about two years. The town of roughly 300 people sits just west of the intersection of State Highway 270 and State Highway 1 and just south of the Canadian River, which serves as the boundary between the Muscogee Nation and Choctaw Nation reservations.

Recently, Chitwood sat down for a conversation about municipal policing within Indian Country reservations and his experiences in law enforcement. In the following Q&A, questions and answers have been edited lightly for clarity and style.

You grew up around here and worked for a military contractor, correct? What was that experience like?

From about December 2004 to about March 2010, I worked for a few different companies, but it was in the Middle East. Being a small-town Wetumka, Oklahoma, guy that had never went out of state or anything like that and then you’re landing at Kuwait International Airport, that was kind of the awakening moment there and a culture shock of all sorts.

When I arrived in Iraq, I want to say it was probably the height of the war as far as the combat operations. It was quite the experience. I learned a lot there. I don’t know how you would really explain it or put it into words. But it was a very humbling experience, seeing the best and the worst of everyone, from our nation and other nations, too. It kind of opened my eyes to how we’re not always the best and not always the brightest, and we’re not always the quickest either. You think you’re the best educated there just because [other people are] poorer than you, but they can speak three languages and they’re a lot better equipped to deal with the area they’re in.

How did you get into law enforcement? What’s the best part of the job, what is the hardest?

I had just been back for a year or so. I worked as an electrician, and I was trying to find out where I belonged. That was the hard part about it, because I’d come from that environment for six or seven years back to small-town Oklahoma, and it’s just, “What do you do?” And one of the police officers there in Wetumka — I was living in town at the time — he asked if I wanted to do a ride-along. You could say I was hooked from then on once I got a taste of that.

I started working at the jail there in Wetumka at the police department. I did that for a year, and while I was doing that I went to the reserve academy in Muskogee and became reserve-certified as a police officer. I did that for two years — I had to work on the street for two years, and then I went to a bridge academy in Ada and became a full-time officer.

The hard part about it is it’s small-town policing. So the politics and whatnot are not on the scale you would think of, but it’s still pressure. You can lose your job pretty quick if you pull over the wrong person or you give the wrong person a ticket. But it seemed like I did pretty good, though, because I just didn’t care. If they did wrong, they did wrong, and hopefully they would realize that. But that was kind of a sticky situation. And obviously when I got fired from Wetumka because of the mayor and whatnot, you’ve seen how that works out. I kind of lost my taste for politics altogether with that crap.

The best part, though, and even in Calvin, too, it’s my county and I’ve grown up here. Especially in your hometown, what better way than (being) the little kid who used to cause trouble running up and down the streets, now you’re at least trying to keep the people safe. That’s kind of the reward I’ve taken from it. Some others might have something else.

You’ve made a couple enemies in your time on the job, and we probably shouldn’t talk about Mr. Jackson until he goes to trial. But what’s it like being in a situation where anybody could get mad at you on any given day, but at the same time you could save someone from a really bad domestic situation on any given day?

That’s the part where you have to — we kind of say — “leave it at the office,” regardless of disagreements or whatever. Even if this person is vile and hates you and calls you the most vile crap in the world, you don’t care. You have to put that aside. It’s tough sometimes — actually, it’s not that tough. You just do your job, do what you’ve got to do and go on with it. Then, deal with the other part of it when it comes around to it. There’s a time and place for everything.

Hopefully, Jackson’s trial — I’m ready to get that over. I’m sure a lot of people are. I know there are victims out there that really, it’s got to be terrible for them, too. But that’s at least some justice for them, I’d hope.

You train K-9 officers, which can be a controversial subject. What drew you to that element of law enforcement, and how can the public be sure that human officers don’t manipulate K-9 officers to “indicate” improperly during drug searches and things like that?

How I got into that was actually when I was working overseas. There’s the military working dog (MWD) program. Some of the dogs, I would help transport those. That was kind of a small niche of a speciality where they didn’t open the doors for anyone. So I just got to peak inside that world a little bit, and when I got to be working as a police officer, the opportunity arose and I jumped on it to get into their K-9 program. I haven’t looked back since.

I’ve always told people that if they made me choose between being a K-9 handler or chief, I would take being the K-9 handler hands down every time. The other part to that question is, it goes back to training. But it goes back to your ethics, too. If you’ve got unethical officers out there doing things like that, that hurts all of us. It makes us look bad, just like any other bad officer who does something like that. So you have to keep the training down.

Making people and the public more aware of how we operate and how we do it and how it’s supposed to be done, that knowledge is not easily accessible. And a lot of officers will hold that, too. They don’t want to share that because, when they retire, what are they going to do? They’re going to train police K-9s or dogs in general. That’s kind of their retirement thing, so they don’t want to let those little secrets out.

Now, there are different trainings or different certifications for different dogs? Give me a little overview of the scope.

A real generic overview is that most people refer to them as single-purpose or dual-purpose (dogs). So Wildflower — the pitbull I got from Throw Away Dogs Project — she’s single-purpose. All she does is narcotics. She’s imprinted with marijuana, cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine. She has no other job than that. Her alert is a passive alert. She’ll sit when she [determines] that the present odor of narcotics is in that area. She’ll sit as an indicator. I’ve just taught that indicator to all of my dogs, as far as a passive sit. I’ve only had one dog that did an aggressive alert, where they would scratch at the area. And I don’t like that, scratching cars and stuff up. All of my dogs are still imprinted on marijuana, with the exception of the little malinois that you’ve seen. I’m actually going to leave that odor off and go that route with her.

The dual-purpose dog can still mean a number of things. They can either be handler protection, they can do patrol routes, they can do tracking, search and rescue, apprehension work. It’s a multi-role dog. More or less, when somebody says “dual-purpose,” it’s really a multi-role dog. Abel, my K-9, he’s dual. He does narcotics. He’ll do tracking. Obviously, I work by myself, so he’s handler protection. That’s my backing officer. And then we can do apprehension and search and rescue with him.

Calvin is in the Choctaw Nation, and your area crosses into the Muscogee Nation. Are you cross-deputized with either tribal department?

When I was with Wetumka PD, I was cross-commissioned through the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

That was before the McGirt ruling?

Yes, that was all before. That was more or less just to help them. You know, they didn’t have many Lighthorse officers. They were spread thin. And a lot of times it was just to secure a scene — to get there, at least assess the situation and help them until they can get an officer to that scene, and then hand it over to them. That’s really no different now.

How are the reservation situations and jurisdictional questions playing out in this area?

In some ways, it’s been harder than what people thought. In some ways, it’s a lot easier. Well, not easier. But some things haven’t really changed. I don’t like the fact that — well, it’s not really what I like or what I don’t like — it’s just my opinion that we’re having to move a lot of stuff that shouldn’t be having to go to federal court.

The other part of it was, you have some of the natives who misunderstood what that ruling meant. They thought they could just do as they wished and speed through town and you couldn’t pull them over, and that’s not how it works either. There’s just a lot of misinformation out there.

A lot of times, too, the trouble is that a lot of the chiefs and the Lighthorse and even the tribes weren’t sure what was going on with a lot of it. I’ve had others who called me and wanted to know what the other tribe was doing. I’d say, “I’m not sure. You’ll have to call them. Give them a shout, or let’s all have a meeting, or let’s all talk and figure out — what do you want me to do with your citizens if I pull them over? What would you like? Call you? Issue the citation and send it to your tribe? Do you want to cross-commission it? Or how do you want to handle it?” And I never really got a clear answer. That was the problem with it.

You still haven’t gotten a clear answer?

No, but just because I didn’t doesn’t mean they didn’t come up with something. I believe what I thought was going to happen is they were going to cross-commission the sheriff’s office and let the deputies do that, since they’re going to be all over the county anyway. And maybe if they have a high concentration of their citizens in a town, they would probably reach out to that area. That’s probably why, with the Muscogee Nation and Wetumka, they have a lot of citizens there. I’m not sure what the count of any nation is in Calvin. It may be a low concentration, it may be high. I don’t think there is, though.

As a law enforcement officer responding to calls at the most local of levels, what advice would you have for state and tribal political leaders?

Make sure that before they make any decisions that they include the officers, or at least come up with something that is clear for everyone — a standardized set of [protocols]. Because if an officer is unsure what to do, you can imagine what the citizens are (experiencing). They have no clue what is going on either.

So make sure it’s clear what you are wanting and what you are wanting to have done. And if you don’t want officers to get involved with something like that, too, then come up with an alternative, because we still have to deal with it. If there’s no clear-cut way of doing it, people tend to come up with their own ways and Supreme Court rulings start getting handed down, and you’re in trouble then.

If I’m not mistaken, your family has had long ties to a local tribe dating back to statehood. Tell me a little bit about that.

As far as I can remember back, I’ve just heard verbal accounts of it. Some of the locals in town who belong to the tribe — I didn’t know about it until they started telling me about it.

Where you’re sitting right now, actually, if you go straight east to that hill way back there, there’s a tree line. My grandfather — it’s either him or my great-grandfather — gave the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town however many acres that is back there and put it on a 99-year lease, which eventually was just given to them anyway.

I believe that is one of the groups that belong to the Muscogee Nation (and has dual citizenship). That’s where their ceremonial grounds are. Matter of fact, you can sit out here at night, and if they’re having any dances up there or singing, you can hear it. That’s just how close it is. It’s just always been that way. It wasn’t no big deal (to me), but everybody loves it. I grew up out here, for the most part.

That’s the problem. My father passed away. Once I learned of it, he had already passed away, so I didn’t get to ask him. Some of the elders know how that came about, and I need to get in touch with them and fill in the gaps to the whole story. I don’t really know all of it. Thelma Noon was the first one who told me about it.

What’s the most bizarre call to which you have ever had to respond?

I think the most bizarre and probably funny is the one with the DUI on the lawnmower. A guy on a riding lawnmower.

He pulled a George Jones?

He pulled a George Jones. I caught him, obviously. He was on a lawnmower, but even the highest gear was walking speed. I could hear it. He had it revved up. The throttle had to be all the way maxed out. I just had basically seen him. He’d seen me. He leans forward like he’s really going to take off, and I could see him just dump that clutch, and it just starts crawling away. And I just walked up to him and turned the mower off. There was a look of disbelief on his face, like, “How did you catch me?”

That was probably one of the more funny ones. Even he — well, he was obviously intoxicated — but he was laughing and having his way with it. It was right there in town in Wetumka. To see the lawnmower getting impounded on the back of the wrecker, I just had to laugh about it.