Despite saying the 2020 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma has caused “havoc,” U.S. District Court Judge Stephen Friot issued an order today denying the state’s request for a preliminary injunction that would block the federal government’s usurpation of regulatory authority over surface mining and reclamation operations on tribal reservation land in eastern Oklahoma.

“Oklahoma has not shown a likelihood of success on the merits of its claims, and it is therefore not entitled to preliminary relief,” Friot wrote.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt’s administration and attorneys will have the option of appealing the injunction denial or continuing to a full trial in front of Friot. A spokeswoman said the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office had no comment on the judge’s initial decision.

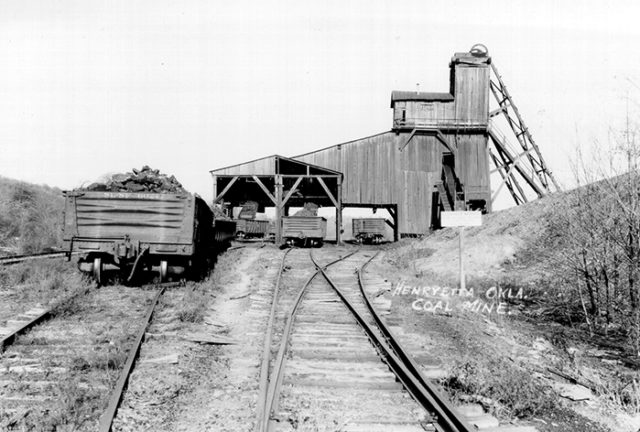

Friot opened his order by discussing the McGirt decision, which affirmed the 18 U.S.C. 1151a Indian Country reservation status of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals subsequently affirmed five other reservations. In May, the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement placed a notice in the Federal Registry announcing that it had taken over jurisdiction on the reservation lands.

Friot said the SCOTUS decision in McGirt had put “the state of Oklahoma, and millions of its citizens, in a uniquely disadvantaged position as compared to the other forty-nine states.”

“Core functions of state government, relied upon by all Oklahomans for over a hundred years, are called into question even though only a very small portion of the land within the newly-recognized reservation is owned by tribes or individuals with a tribal affiliation,” Friot wrote. “The result the court reaches in this order is a prime example of the havoc flowing from the McGirt decision. But the result the court reaches here is a legally unavoidable consequence of the application of federal statutory law in light of that decision.”

‘The plain language of SMRCA says otherwise’

While Friot’s order emphasizes his concern for the impact of the McGirt decision — which he called a “disaster” for Oklahoma during a Dec. 2 hearing — the judge found issue with each of the state’s arguments in the surface mining case.

“Oklahoma argues that it is likely to succeed on its declaratory judgment claim because [the Surface Mining Reclamation and Control Act] does not give OSMRE exclusive jurisdiction over Indian land in the absence of a tribal regulatory program,” Friot wrote. “Because the plain language of SMCRA says otherwise, the court disagrees.”

He also critiqued the state’s argument regarding a definition of “federal Indian reservation” on the FAQ page of the Bureau of Indian Affairs website. The website definition says the federal government must hold land in trust on behalf of the tribe for it to qualify as a reservation.

“This argument fails for several independent reasons,” Friot wrote. “First, Oklahoma fails to persuasively explain why an out-of-context statement from the BIA’s website should inform the court’s interpretation of SMCRA. Second, SMCRA’s definition of Indian lands plainly encompasses land not held in trust because the definition includes fee-patented land within a reservation’s borders.”

Friot did say that a separate argument from the state “is not without appeal” regarding the SCOTUS decision in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, a 2005 case about whether the Oneida Nation was part of an Indian reservation and, thus, exempt from local taxation.

The Oneida Nation had sold much of its reservation in the early 1800s but reacquired the land almost 200 years later, subsequently claiming it was exempt from local taxes. In an 8-1 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that by giving up the land initially — and because regulatory authority had been exercised by state and local governments for nearly 200 years — the Oneidas had “relinquished governmental reigns” and were no longer exempt from state and local taxation authority.

The state of Oklahoma argued that the same doctrine applied to the Muscogee reservation. Although he noted the relevance of the City of Sherrill decision, Friot said the argument was inapplicable to the surface mining jurisdiction matter.

“The court is hard-put to apply the equitable considerations which were decisive in Sherrill where, as here, the federal defendants invoke the plain terms of federal statutory law,” Friot wrote. “There can be little argument that McGirt’s recognition of the ongoing existence of the Creek Reservation will disrupt significant and justified expectations concerning the character of the land.

“For that reason, Sherrill may well be a powerful weapon in Oklahoma’s attempts to resist claims that the Creek Nation or inhabitants of the reservation enjoy broad immunity from local regulation. But Sherrill provides no help to Oklahoma in this case, which deals not with an Indian tribe’s attempt to re-possess land or evade state regulation, but with the application of the plain language of a federal statute which specifically addresses the matters in dispute in this case.”

State missed deadline with APA concern

Lastly, Friot declined to accept the state’s argument that the federal agency had violated the Administrative Procedure Act because a public comment period was not allowed. Friot, however, noted that the agency had communicated its intention to usurp surface mining jurisdiction in an April 2 letter to the state, which the judge said started a procedural 60-day clock for challenge.

“Oklahoma’s failure to challenge OSMRE’s decision within sixty days defeats three of its claims: count two, asserting that OSMRE’s decision was arbitrary and capricious under the APA; count four, asserting that the notice of decision was

arbitrary and capricious under SMCRA; and count five, asserting that the notice of decision failed to satisfy APA’s procedural requirements,” Friot wrote. “All that remains, then, is count three, which asserts that OSMRE’s decision to deny Oklahoma federal funding for its regulatory and reclamation program was arbitrary and capricious in violation of the APA.”

The judge said “it is not arbitrary and capricious to refuse to fund an unauthorized program.”

In his conclusion, Friot reiterated his concern about the scope and extent of the McGirt decision’s impact on the state of Oklahoma, and he emphasized that his initial order marked a “narrow ruling interpreting a single federal statute.”

Friot wrote:

The majority opinion in McGirt candidly recognized that the Creek “reservation,” as an Indian reservation in the commonly accepted sense, has been thoroughly hollowed out by more than a hundred years of legal, extra-legal, economic and demographic events. Thus, the Creek Reservation, even as found by the Supreme Court to exist, is essentially a perimeter, a line zig-zagging around a major swath of eastern Oklahoma (including most of Tulsa), within which Oklahomans of all races are born and live their lives, oblivious to any notion that the lands on which they live their lives are in a category apart from the lands on which their fellow citizens would live their lives in any other state (or in the western half of Oklahoma). The court is nevertheless compelled to conclude that Oklahoma has not shown a likelihood of success on the merits of its claims, and it is therefore not entitled to a preliminary injunction. In reaching this conclusion, the court is mindful that SMCRA has become one of the federal civil statutes McGirt suggested could be “trigger[ed]” by its finding that the Creek Reservation persists today. 140 S.Ct. at 2480. But it bears repeating what was said at the outset: this is a narrow ruling interpreting a single federal statute. The court goes no further in this order than to conclude that Oklahoma has not met its burden of showing that it is entitled to preliminary injunctive relief.

On the broader topic of the McGirt decision’s impact, the state of Oklahoma is pursuing several other challenges that ask the U.S. Supreme Court to limit the McGirt decision’s applications or overturn it altogether.

Read Judge Stephen Friot’s order