One of the more niche bills before the Oklahoma Legislature this session may be HB 3281, which seeks to ensure that certain controversial elephant-handling techniques “shall not be considered cruelty to animals.”

The bill was introduced by Rep. Justin Humphrey (R-Lane), whose district includes Hugo, a town of about 5,000 that bills itself as Circus City, USA. Hugo has historically been the winter headquarters for a number of circuses, and it is now home to the Endangered Ark Foundation, a “retirement ranch for circus elephants” that gives guests the opportunity to “get up close and personal” with the animals.

Humphrey said he filed the bill, called the Endangered Ark Foundation Preservation Act, in order to protect the way the organization cares for its animals and presents them to the public.

“What we want to do is have a great place where people can interact with our elephants, that we can educate people about our elephants and we can promote tourism (and) bring people to our community,” Humphrey said. “It’s a win-win. It’s a win for the elephants, it’s a win for our district, and it’s a win for the people of the state of Oklahoma.”

Karyn Olmos, director of the Endangered Ark Foundation, said in an email that the bill would “prevent any group from attempting to remove the elephants from their home they have always known and from the humans they are accustomed to being with and handling their care and well being.”

Local animal-welfare advocates, however, say the bill is regressive and out of line with current approaches to elephant handling, presenting a danger to both animals and humans. The foundation’s practice of letting visitors interact with elephants is also the subject of a lawsuit that alleges a guest was attacked by an elephant and grievously injured in 2021.

HB 3281 passed the House Agriculture and Rural Development Committee 9–1 on Feb. 8 and is awaiting a hearing on the House floor.

‘Guide’ vs. ‘bull hook’

At the heart of HB 3281 is the use of guides and tethers in elephant handling.

Guides, also known as bull hooks, are long sticks with a pointed hook on the end. Many animal-welfare advocates say they are inhumane, and they have been banned in some states and by prominent zoo and animal sanctuary accreditation organizations.

Olmos said the tool has been unfairly maligned largely because of the term “bull hook.”

“It seems as though the controversy of some stems from a name given to the tool used for handling the elephant many years ago and a misconception of what it is used for in handling techniques,” she said. “Our fully trained handlers use a tool called an ‘Elephant Guide’ to direct and cue an elephant with verbal instructions. The guide is simply that — a guide. (…) It is used with verbal instructions and is never to be used in a way to harm or injure the elephant.”

When the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, a major accreditation organization, decided in 2019 to ban bull hooks for its member institutions, the organization’s CEO, Dan Ashe, told the Washington Post that the vast majority of AZA-accredited facilities had already phased out the use of guides. And, though the tools were generally used in a non-abusive manner, he said, the ban was meant to “reflect modern zoological practice.”

Tethers are chains, ropes or cords used to restrain an elephant by its legs. They are sometimes needed for short periods of time, such as during medical procedures, but, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association (which does not support bull-hook bans), tethering elephants on a regular basis can cause significant harm and distress.

HB 3281 defines the use of these tools as a part of “free contact” elephant handling, which occurs when people interact with elephants without barriers between them — as opposed to “protected contact.” Major zoo, sanctuary and veterinary organizations say free contact should be limited and used with extreme caution simply because elephants are dangerous.

Humphrey’s bill would enshrine these tools and methods as permissible in Oklahoma for nonprofit entities such as the Endangered Ark Foundation.

According to the bill’s Senate sponsor, Sen. David Bullard (R-Durant), impetus for the bill stemmed from criticisms of the foundation by animal-welfare activists.

“They’re trying to lie and say that [the elephant guide] is used to beat them,” he said. “And it’s not true. So we’re just safeguarding that.”

The exact wording in the bill reads: “It shall not be considered cruelty to animals as provided in Section 1685 of Title 21 of the Oklahoma Statutes for licensed operators of a nonprofit entity caring for elephants to practice free contact and protected contact.”

Rep. Trish Ranson (D-Stillwater), the only member of the House Agriculture and Rural Development Committee who voted against the measure, said she opposed it because of what she called broad wording.

“To me, that section right there could possibly protect someone from animal-cruelty charges,” she said. “Now, let’s say that they use free contact or protected contact, yes, but they abuse it. If they abuse it, they can hide under that. Because they can say, ‘Oh, under statute that’s not considered cruelty to animals.’ So that’s why I think it goes too far.”

Hugo circus accused of animal-welfare violations

Kristy Wicker, an animal-welfare researcher in Oklahoma, called the protection of bull-hook use “a step backward.” She also faulted the bill for being specifically intended to protect the Endangered Ark Foundation.

“Anything that’s designed more to help one foundation or one organization versus for the good of all the animals in the state — to me, that’s always a concern,” Wicker said. “We’re talking about changing state laws for one organization, and in this case it’s something that is not even considered best-practices for those that are involved in captive wildlife issues at a more humane and accredited level.”

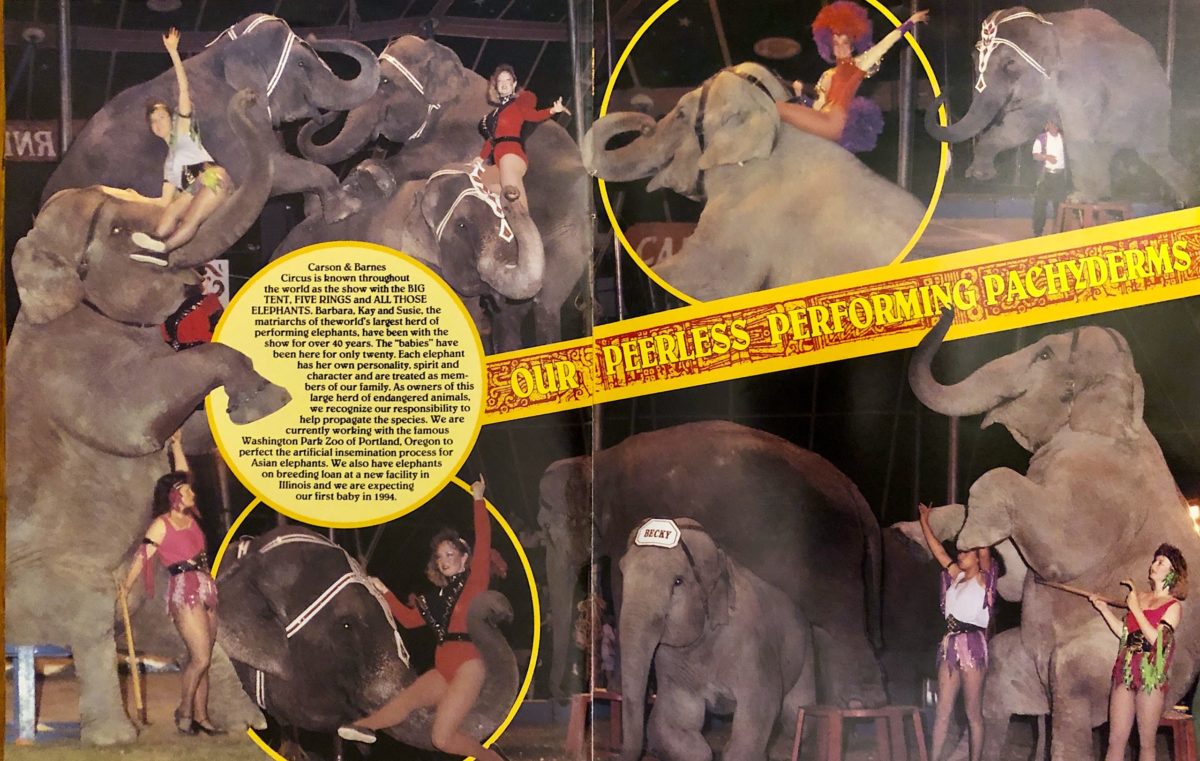

Wicker was the main author of the Kirkpatrick Foundation’s 2016 Oklahoma Animal Study. The study notes the relationship between the Endangered Ark Foundation and the Hugo-based Carson & Barnes Circus. The founders of the circus, D.R. and Isla Miller, set up the foundation as a private nonprofit in 1993, and there has been overlap in the leadership of the two organizations through the years.

According to a report by the Humane Society, Carson & Barnes has “a long history of abysmal animal care and elephant rampages.” The report lists incidents going back to 1989 and numerous U.S. Department of Agriculture citations for Animal Welfare Act violations, including “using a bull hook with ‘excessive force’” and “failure to properly handle elephants.”

“In a nutshell, we shouldn’t be amending our animal-cruelty statute to preserve and protect something so cruel,” said Cynthia Armstrong, Oklahoma State Director for the Humane Society of the United States. “And we absolutely should not be doing that for this outlier group that has such a miserable track record of public safety and animal welfare.”

Olmos defended the foundation’s treatment of its elephants.

“Our animals are loved and cared for and are given special treatment including personal daily spa care and weekly pedicures, among other things to keep them healthy and safe,” she said. “(…) Our elephants have been around and interacted with humans their entire lives and are very accustomed to human interaction.”

The most recent incident listed in the Humane Society report occurred in 2021 and is the subject of a Oklahoma County lawsuit in which a woman named Dana Garber says she was “attacked without provocation by an adult elephant” while visiting the Endangered Ark Foundation and was “temporarily and permanently disabled” and “permanently disfigured.”

Olmos declined to comment on the incident because the lawsuit is ongoing.

Armstrong argued that the Endangered Ark Foundation’s desire to allow free contact between elephants and visitors is, itself, a problem.

“They shouldn’t do close encounters with elephants,” she said. “It’s just dangerous. (…) I don’t know why they think they’re going to continue this without other incidents. Even if there were no other incident, it’s a cruel handling technique that is just no longer acceptable in modern practice.”

Several photos on the Endangered Ark Foundation website show guests posing with elephants without a barrier, including for professional photography sessions.

According to Olmos, the foundation takes measures to protect guests.

“There really are not any times when our guests have totally free-contact interactions, as we will always have trained staff with the guests at all times,” she said. “At certain times, guests may have the opportunity to feed an elephant or even assist staff with the daily spa treatment, protection of the guests and the elephants are of utmost importance.”

Humphrey was dismissive of criticisms leveled at the foundation.

“The interesting part to me is you have a lot of people who’ve never handled an elephant, never worked with elephants trying to tell people who have handled them all their life how they should do their job,” he said. “Plus, these people who raise elephants dedicate their life — they love these creatures. (…) Their livelihood comes from these animals. They’re not going to abuse them. These are the best-treated animals in the world.”

Regarding safety issues, Humphrey expressed similar confidence in the foundation.

“I think that these people have handled elephants for a long time, and they have restraints on,” he said. “And there will be some wooden fences or some fencing, you know what I’m saying? Now could an elephant tear that down pretty easily? Sure. Is there possibility that something like that could happen? To my knowledge, they have not had it happen. I do know that the elephants have gotten out and gotten on the highway before.”

Bill aims to reduce cockfighting penalties

HB 3281 is not the only Humphrey bill ruffling the feathers of animal-welfare advocates this legislative session.

He also proposed HB 3283, which would amend the law prohibiting cockfighting so that it would only apply to fights in which the birds were outfitted with “spurs, knives, or gaffs.” It would also reduce the penalty for participating in cockfighting from a felony to a misdemeanor — a change Armstrong said would allow cockfighting to flourish because misdemeanor fines would be a drop in the bucket compared the amounts of money being exchanged in the sport.

Oklahoma was one of the last states to outlaw cockfighting, which happened with the passage of State Question 687 in 2002.

Humphrey said his bill is not designed to overturn that vote — which passed with 56 percent of the public vote — but to bring “balance” to sentencing laws. For comparison, he pointed to recent reductions in sentencing for drug possession and the fact that abortion is not criminalized.

“I don’t know about everybody else in Oklahoma,” he said, “but that seems insane to me.”

HB 3283 passed the House Criminal Justice and Corrections Committee unanimously Feb. 10.

(Correction: This article was updated at 10:45 a.m. Tuesday, Feb. 28, to correct Cynthia Armstrong’s title.)