In late March, the Oklahoma State Capitol rotunda filled with a dissonant symphony of protesters chanting, “Go away, OTA!”

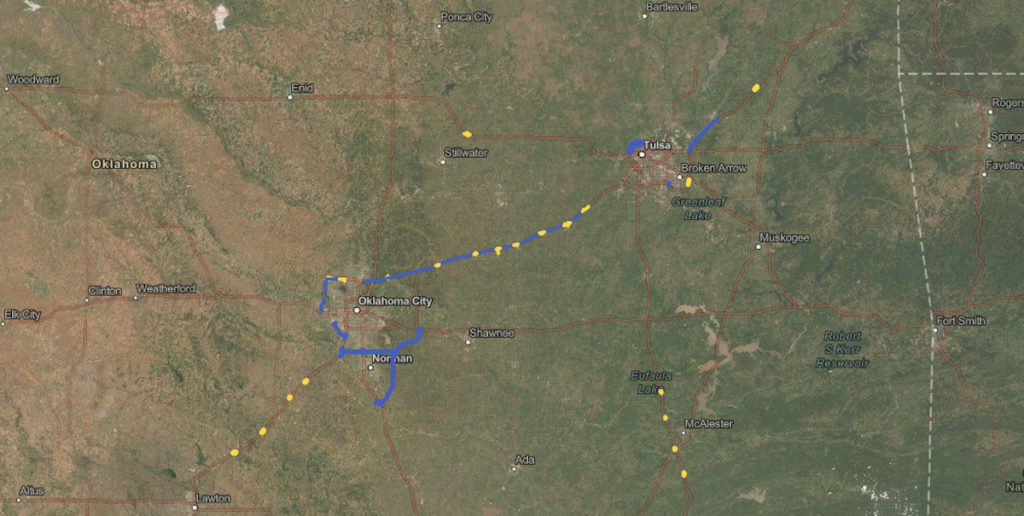

The protest, which included some legislators, came about a month after the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority announced a long-term plan for the state’s turnpike development, dubbed the Advancing and Connecting Communities and Economies Safely Statewide, or “ACCESS Oklahoma,” plan. Officials say it aims to address Oklahoma’s “highway infrastructure needs” and includes four major turnpike expansion projects across the state, each intended to create new routes and connections between existing pay roads. Three existing turnpikes are set to be widened as well.

The future sketched out in the turnpike plan has sent tensions into overdrive in areas affected by the proposed construction, particularly surrounding expansions in the eastern and southern parts of Cleveland County. New connective routes in those areas, intended to link the Kickapoo Turnpike to I-35 just north of Purcell, are slated to run through the mostly rural land to the west of Lake Thunderbird, and through the semi-rural area of north Norman along Indian Hills Road, just outside the city proper.

Opponents of the plan, many of whom are residents and homeowners in those areas, say that construction of that so-called “Southern Extension” stands to threaten more than 600 homes.

The Turnpike Authority, with support from Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, has said that the expansion plan is a necessary solution to the state’s increasingly dangerous highway traffic problems and that the actual number of homes that will have to be removed is likely to be far lower than has been reported.

The Turnpike Authority hopes to break ground on the project later this year, after an environmental study has been completed and legislative approvals have been passed. The department has said that, for all intents and purposes, the turnpike expansion is a certainty at this point.

Opponents, however, backed by a surprising coalition of mayors, state legislators, attorneys, and activists on either side of the political divide, say that the plan is nothing more than a cash grab for turnpike bondholders and that they will do everything they can to prevent or halt the project.

On Monday, 24 plaintiffs filed a lawsuit challenging the Turnpike Authority’s plans in Cleveland County District Court. Today, leaders of the coalition attended a meeting of the Council of Bond Oversight in Room 100 of the State Capitol to express their frustrations with the proposed turnpike projects. The bond board unanimously authorized the Turnpike Authority to secure a $200 million line of credit with Wells Fargo to help with project financing.

Accelerating into the future

“It’s pretty well set,” said Jessica Brown, strategic communications director of what is known as the Oklahoma Transportation Cabinet, a catch-all position that puts Brown in charge of communications for the Oklahoma Department of Transportation, the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority and the Oklahoma Aeronautics Commission.

When asked if all the protests, challenges and pushback against ACCESS might change things or delay the OTA’s hopes of breaking ground later this year,, Brown made it clear that, with the exception of some fine-tuning, the plan is mostly a foregone conclusion.

“There will be considerations for environments and properties and such that we’ll take into consideration and tweak,” Brown said, “but it’s pretty well set at this point in time.”

Those “environments and properties and such” are at the heart of the issue for the hundreds of homeowners who potentially stand to either lose their homes or have their surrounding environment dramatically changed.

“These people’s lives will be turned upside down to slightly improve commute times,” Inger Giuffrida, executive director of WildCare, a wildlife rescue and rehabilitation center in Noble, said at the Capitol on March 23.

WildCare’s headquarters sit near the proposed turnpike path, and Giuffrida said the building will either be demolished or subject to road-borne pollution that could be harmful to the group’s animal patients and their local habitats.

“Make no mistake, while we’re here to speak for wildlife and their habitats, we are equally concerned about the impacts of this project characterized as having ‘minimal human impact.’ That is false,” Giuffrida said “People will have their homes needlessly destroyed, become displaced, and/or lose investments in homes and properties, euphemistically referred to by the OTA and the engineering firm they have contracted to manage this project as ‘rooftops.’”

According to Brown, the OTA has good reason to go ahead with the project in the face of backlash and protests.

“Really, the impetus for this was safety,” Brown said. “We’re having wrecks on I-35 through the metro way too regularly. (…) We use traffic counts to predict what will happen in 30 years. Oftentimes, we don’t get the latitude to project or think forward, and that’s what this plan does. We have to do something. We don’t have a choice.”

ODOT spokesperson James Poling elaborated on the concerning traffic numbers.

“In eight years, we saw an increase in average daily traffic on I-35 by 20,000 cars per day,” added ODOT spokesperson James Poling. “If Cleveland County continues to grow by 25,000 or 30,000, the traffic is going to increase if we do nothing. This is addressing what will become a problem if inaction is taken.”

That sentiment was echoed by Senate Appropriations and Budget Chairman Roger Thompson (R-Okemah).

“I’m certainly pro-turnpike,” Thompson said. “How it’s going to impact the areas, I think, needs to be a study that we need to talk about. However, when we look at the traffic that is coming through Oklahoma today, we have got to get some traffic off of downtown Oklahoma City. So if we can do something with turnpikes to take that traffic off, we need to.”

Guiffrida remains unconvinced.

“Of course they claim safety,” she said. “However, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration determined that speed, people not wearing seatbelts, and driving under the influence to be the most prevalent causes of highway fatalities. The turnpike addresses none of these. These claims about safety seem spurious.”

The driving forces

Calling into question the stated motivations behind this multi-billion dollar turnpike expansion is a common theme among turnpike opponents, who often argue that the project is actually intended to serve the financial interests of OTA bondholders.

Oklahoma’s turnpike expansions are not funded out of the state’s appropriated budget, but rather by bonds that are bought by investors and guaranteed by anticipated proceeds from turnpike tolls. According to a recent report by the State Auditor and Inspector’s office, the OTA already has approximately $1.72 billion in outstanding revenue bonds.

This arrangement was not quite the goal when the Legislature established the OTA, in 1947, for the creation of the Turner Turnpike between the Tulsa and Oklahoma City metro areas. Originally, the plan was for money from tolls to be used to pay off the bonds completely, after which the turnpike could become free to use and could revert to control by ODOT, like other state highways. In the 1954, however, Oklahoma voters passed a measure that allowed for revenues from one turnpike to pay for construction of new turnpikes around the state, requiring more bonds to be issued and more interest to be paid to investors, effectively trapping the turnpike system in a cycle where the roads never become free to use.

To date, none of the turnpikes built since the OTA was established have paid off the agency’s debts or transferred out of OTA control.

“The turnpike is not a for-profit (enterprise),” Brown said. “All those tolls go right back into those turnpikes for the public.”

The turnpikes themselves might not be making money, but there are significant profits available to those who invest in OTA bonds.

The OTA’s fourth quarter financial report for 2021 showed payments of “interest expense on revenue bonds outstanding” totaling nearly $70 million year-to-date. Financial ratings giant Fitch Ratings gives the investment viability of OTA bonds a “AA-” mark.

The question of when (or if) the state might successfully pay off the bonds and transfer control of the turnpikes to the Oklahoma Department of Transportation was further complicated in 2019, when Gov. Kevin Stitt appointed Tim Gatz, executive director of the OTA since 2016, to also be director of ODOT. Stitt also named Gatz the state’s secretary of transportation, all while retaining and concurrently holding his director position at OTA.

That appointment, and a major pay bump in 2021, placed Gatz among the highest-paid state government officials in Oklahoma. It also effectively makes Gatz the gatekeeper of all transportation policy across the state.

Many in the anti-turnpike opposition (particularly in the now 6,700-strong “No More Turnpikes, Oklahoma” Facebook group) have voiced concerns about the ethical implications of one person heading up both a state agency designed to eventually relinquish control of its primary revenue generators and the department that would assume control if debts were ever paid back in full.

The speed bumps

Outspoken critics of ACCESS Oklahoma, and of the OTA’s continuing existence, have come from all corners of Oklahoma politics. So far, on the legislative level, their efforts are mainly focused on simply slowing the process.

Sen. Rob Standridge (R-Norman) has authored SB 1610, a measure that would allow the Legislature to review and potentially modify the plan for the South Extension Turnpike, though the bill’s current form stops far short of allowing lawmakers to cancel construction. The measure has been sent to a conference committee, meaning it is still alive amid negotiations among stakeholders.

Earlier in the 2022 legislative session, Rep. Merleyn Bell (D-Norman) attempted to attach an amendment to a separate bill that would have explicitly removed the eastern Norman and Moore areas from the turnpike plan, but the amendment was blocked.

Republican gubernatorial candidate Mark Sherwood attended the March 23 Capitol rally and vowed that, if elected, he will do everything in his power to shut down the turnpike plan. (In 2002 and 2018, Tulsa attorney Gary Richardson also ran for governor, with abolishing the Turnpike Authority as a top priority.)

Sen. May Boren (D-Norman) has attempted to push for tighter regulation and review of turnpikes in an effort to ensure that citizens’ voices are taken into account at the upcoming public meetings that OTA will be hosting specifically to allow residents to voice their concerns about to the plan.

Boren doesn’t seem particularly hopeful about legislative pushback, however.

“I don’t know how we can do a legislative fix for highway policy,” she said. “The way it’s structured right now, with the OTA and the Department of Transportation all being under one person, that is the person that looks at one option versus the other. That’s done all at the department level, and I don’t know when they have those conversations.”

The long road ahead

With even legislators coming up short on ideas of how to prevent the turnpike construction, opponents of ACCESS Oklahoma are pursuing other avenues.

Longtime attorney Stan Ward, whose house sits directly in the path of the proposed southeastern Cleveland County extension in far east Norman, cut short his retirement to help develop a plan for legal recourse against the OTA. One aspect of that effort is looking for potential violations that might invalidate the plan.

“I think, quite frankly, they’ve fallen short on one big thing, and that’s the Open Meeting Act,” Ward said at the Capitol. “If you do not comply with the Open Meeting Act, that makes any action taken, if it’s a ‘willful violation,’ void. So we have people that are going to be looking very carefully at the agendas and the minutes over the last five years, at least, of the OTA to see if, in fact, they have given notice that’s reasonably calculated to tell ‘we the people’ of the business to be transacted.”

Amy Cerato, a professor of geotechnical engineering at OU, whose house is also in the proposed turnpike path, is one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit filed Monday. She is also part of an effort focused on appealing to larger federal environmental protections.

“Not only do these proposed routes impact our drinking and groundwater, but they will destroy a rare geologic formation that makes our small part of this planet so special,” Cerato said, speaking of the barite rose, or “rose rock,” the official state rock of Oklahoma since 1968.

“These exquisite natural wonders are found only one place on Earth,” she explained, “in a thin band between Lake Stanley Draper and Noble.”

Cerato said she is working with the Oklahoma Geological Survey to apply to have the area federally designated as a protected “geo-heritage site,” a move that would prevent any construction or environmental disruption in the region.

Of course, all these efforts are likely to take years of studies, filings and appeals, and though the projected timeline for completing the ACCESS plan is up to 15 years, the process has already started rolling. An OTA-commissioned environmental study by OKC-based environmental engineering firm Garver is slated to be completed by this coming December, and some homeowners in the area have already decided to sell.

Despite the lawsuit, legislative pushback and possibly even federal intervention, ODOT and the OTA remain confident that the ACCESS Oklahoma plan is going to be a reality.

“Future studies and future design work could result in some minor changes in the route,” Poling said. “But no major changes are anticipated.”

(Correction: This article was updated at 10:55 a.m. Wednesday, May 4, to correct a reference to the Turnpike Authority’s role in construction. It was also updated to reflect the Council of Bond Oversight’s approval for the agency to secure a line of credit and to clarify language related to the number of turnpike projects and the history of the program.)