On Nov. 15, exactly one week after the 2022 midterm elections, Oklahoma City Ward 2 Councilman James Cooper kicked off his 2023 reelection bid at the Tower Theatre in uptown Oklahoma City. More than 1,000 miles away, former President Donald Trump was announcing his 2024 campaign to a nation still watching some states still count votes from Nov. 8.

At Cooper’s OKC party, supporters sipped drinks from an open bar and were invited to donate to his first reelection effort against Chris Cowden, a REALTOR and former development director for the Oklahoma City Archdiocese.

When Cooper’s campaign manager, Aaron Wilder, introduced his candidate to a group of about 100 supporters, he acknowledged that people might not be fired up for another election.

“You have every right to be tired after what we’ve been through,” Wilder said. “If you are weary at this moment, I need you to go home and rest, because we need you in order to help James Cooper get reelected.”

It’s little wonder that Wilder felt the need to address the issue of voter fatigue. Cooper’s campaign launch came on the heels of an exhausting 2022 election cycle that isn’t even over yet, as Georgia will hold a Dec. 6 U.S. Senate runoff between incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) and former football star Herschel Walker.

In Oklahoma, voters were subjected to tens of millions of dollars in dark-month advertising in 2022 that was often negative and sometimes misleading. Federal races and the highly contentious but ultimately anticlimactic governor’s race between incumbent Gov. Kevin Stitt and Republican-turned-Democrat Joy Hofmeister saw the greatest financial expenditures. Heated primaries and Republican runoffs also asked voters to make a variety of decisions about legislative seats. Local propositions and county officers were decided this year as well.

Now, the 2023 elections are coming up fast. A handful of communities will head to the polls Jan. 10 to consider local propositions. And with candidate filing set for Dec. 5-7, many towns and cities will vote Feb. 14 for municipal positions and school board seats.

In Oklahoma City, residents will decide up to four council seats in the February election. Norman voters will also decide up to four council seats, as well as on $354 million in school bond proposals. In Edmond, the mayor serves an astonishingly short two-year term, meaning Mayor Darrell Davis will be up for reelection, along with two other Edmond City Council members. Some Tulsa County residents will vote in municipal elections, and school board seats across the broader metro could draw a variety of candidates.

And in March, voters across the state will go to the polls to decide the fate of State Question 820, which would legalize marijuana in Oklahoma for recreational use by adults over 21. While Oklahomans have embraced medical marijuana, with about 400,000 registering for a patient license, the recreational marijuana campaign could prove contentious and may draw an organized opposition.

In Oklahoma City, voters are also expected to decide on a funding package for a new arena for the OKC Thunder. That proposal could appear on a special election ballot near the end of 2023.

The seemingly endless stream of campaigns and elections can take a toll on voters. In 2016, nearly 70 percent of respondents to a Harris Poll said the election was a source of stress in their lives. In a 2020 Pew Research poll, nearly 60 percent of respondents said they experienced fatigue in the run-up to Election Day.

Examining voter fatigue in America

Compared to many other countries, the United States has a lot of elections. In the United Kingdom, general elections are held every five years, with some off-year by-elections taking place in the interim. A citizen of Germany votes every four years. Voters in Ireland can go as long as five years between general elections. In most countries, there is no equivalent to America’s midterms.

In the U.S., a huge amount of money is spent to decide these elections. An estimated $6.4 billion fueled the midterm elections in 2022. That includes dollars spent by campaigns themselves and by dark-money groups that aren’t subject to contribution limits. Much of that money goes toward a blizzard of ads that play on fears and prejudices while clogging TV channels and stuffing mailboxes from Bangor to Bakersfield.

University of Oklahoma political science professor Tyler Johnson said voters may experience different types of fatigue.

“First, you have a volume issue that will vary depending on where you live,” Johnson said, referring to the sheer number of positions up for election that voters have to think about. “In some places, they don’t have runoffs, and in other places they do have them. Some places have ranked-choice voting but don’t have primaries. And you often have multiple things on the ballot that voters are asked to decide on.”

Election advertising and news coverage can also be exhausting, both because of quantity and tone, which is often negative and/or hyperbolic.

“When you’re constantly being told this is the most important election ever in media coverage and by candidates, then you combine that with the closeness of elections in some places, I could see how it would be fatiguing,” Johnson said. “All of those things, including negative advertising, can influence some people to just sit out or make those who do vote regularly less enthusiastic about the current election.”

At the national level, Donald Trump announced his 2024 presidential bid just a week after the midterms, while some states were still counting votes. President Joe Biden, should he decide to run for reelection, is expected to announce early next year. In practice, U.S. presidential campaigns begin whenever candidates decide to start campaigning. Media coverage inevitably follows.

“There is an argument to be made that, compared to other democracies, we have a permanent campaign,” Johnson said. “It seems like it’s never-ending in the United States. In a lot of countries, they don’t have these fixed electoral calendars. They don’t vote as much. That’s the system we’ve chosen. There’s really no release valve. There is no taking the pressure off because we’re always looking forward to the next election.”

Johnson expects the dynamics of American politics will not change in the foreseeable future and that division and increasingly unpleasant rhetoric are likely here to stay.

“People seem to be constantly frustrated with government, and national politics are on a knife’s edge with control of the Senate and White House,” he said. “Every few years, it bounces back and forth, but the country is so closely divided it’s hard to see a world where the temperature goes down.”

‘As soon as you finish off your race, you’re campaigning again for the next one’

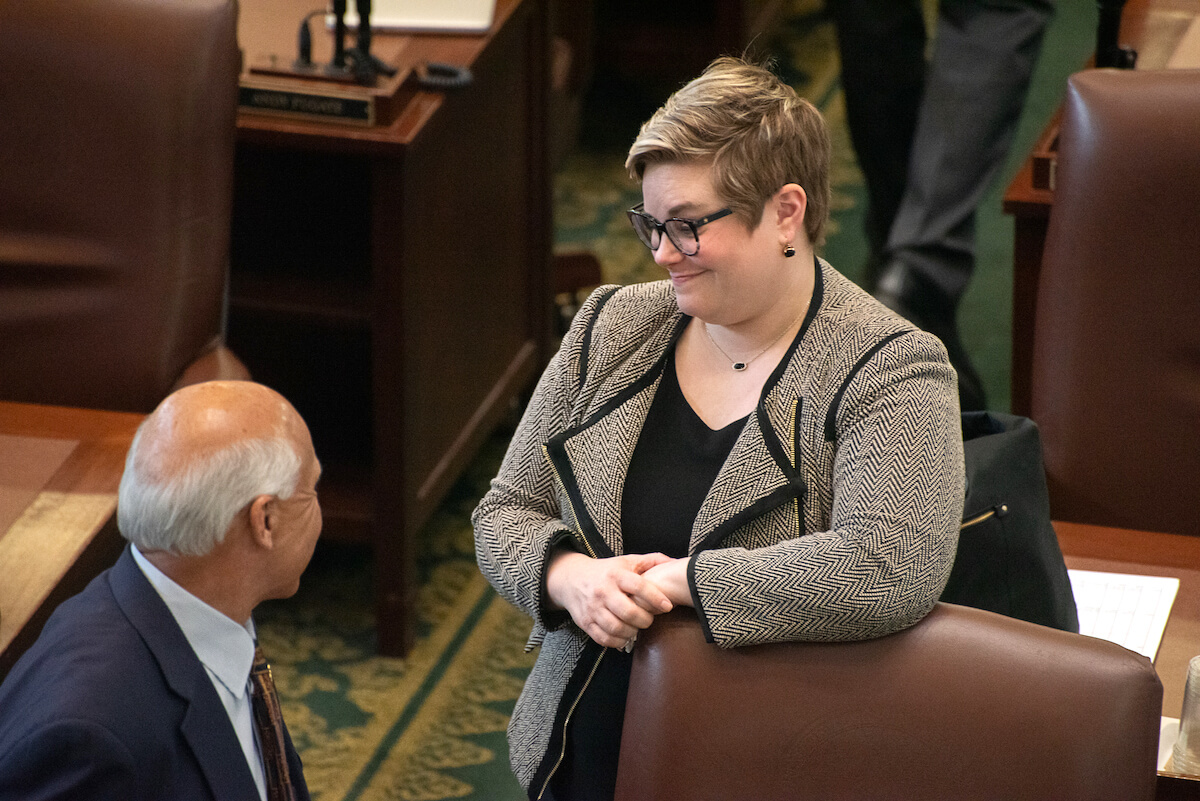

Former Rep. Emily Virgin (D-Norman) recently departed the Oklahoma House after reaching her term limit of 12 years. During that time, she faced the prospect of running for reelection six times. She said the biennial election for House members can make lawmakers feel as if they are constantly raising money and convincing people to vote for them.

“It’s especially true in the House, where you’re up every other year,” she said. “You really never stop campaigning.”

Former Rep. Dustin Roberts (R-Durant) also reached his term limit this year, though he did run for the Republican nomination for Oklahoma’s 2nd Congressional District. Roberts said the frequency of elections can be intense, but he said it has some advantages.

“As soon as you finish off your race, you’re campaigning again for the next one,” he said. “In some ways that’s good, because you’re always talking to people. But people get tired of politics, and I think candidates do, too.”

And campaigning isn’t just about pancake breakfasts at the local Rotary Club or hiking door to door to meet voters. Campaigns require money, and in most cases raising that money falls on candidates.

“It’s sort of a necessary, evil and it’s always an awkward process asking people for money,” Virgin said. “I felt like there was a constant focus on money. You are able to get the work done, but in the back of your mind, you’re worrying about raising money. And I don’t know how most people did it, but for me it was sitting at my desk and making phone calls asking people to contribute. That takes you off knocking on doors and meeting with constituents.”

Roberts found the process similarly unpleasant.

“I would say the money raising is the worst part of being a candidate,” he said. “You’re constantly calling people. It’s almost as if you can’t have a conversation without trying to raise money. Everything revolves around that when you’re running a campaign.”

Virgin said the constant need to raise money was more exhausting than the quick turnaround between campaigns.

“I think the solution probably isn’t longer terms but getting money out of campaigns as much as possible,” She said. “You could lengthen terms, but I think it’s important that a legislative body is close to the people, and the House is designed that way because we’re up every other year. It’s constant, and I think some of that political pressure weighs heavily on the House.”

Roberts said he believes removing money from politics is not a realistic goal, but he suggested that raising term limits from 12 to 16 years might be a way to help those who do serve make a bigger impact.

“When you look at it, 12 years seems like a long time, but it’s a short time when you think about solving issues in the district,” Roberts said. “It’s hard to move the needle as a newbie, because there are always going to be senior members. Eventually you can work your way up to a chairmanship and that helps get things done, but it takes time. Before you know it, you’re out of time.”

‘What I do hate is the dark money’

The attendees at Cooper’s campaign kickoff in OKC were relatively progressive and politically engaged. Among them was Ward 2 resident Brenda Johnston, a progressive voter who said she supports Cooper because he shares her priorities for the city.

Heading into the Feb. 14 City Council election, Johnston said she doesn’t have fatigue from the number of elections voters are asked to participate in.

“I’m absolutely still engaged and planning on voting,” she said. “I’m a little disappointed in some of the [November] outcomes, obviously. … But I don’t think I have election fatigue that would cause me not to vote.”

Johnston did express some exhaustion with the content of campaigns, however.

“The advertising was awful, but I was able to see through that because so much of it was junk,” she said. “I also got so many mailings that were just junk.”

Steve and Jennifer Watson have supported Cooper since his first run for the OKC City Council, in 2019. The couple met with him to discuss solutions for a homeless encampment that had sprung up behind their home. They wanted a solution that would give the people living in the camp a way to find housing. They got more than they bargained for.

“We met James to talk about one issue that was important to us, but we quickly found out that there were a lot of other things James cared about that we care about, too,” Jennifer Watson said.

Steve Watson is looking forward to voting Feb. 14, even though he and Jennifer were disappointed to see Stitt win another term and Democrat Jena Nelson lose to Republican Ryan Walters after a nasty campaign for state superintendent of public instruction.

“We’re pissed off,” Steve Watson said. “We’re pissed off that Joy lost and Jena lost. But Carrie Hicks won for us. Julia Kirt won for us. We’re still engaged. We want James to win. We like what he is doing and we support him.”

Jennifer Watson said there is no way she would consider sitting out the next election.

“You have to count the small victories,” she said. “We know living in Oklahoma as a progressive is going to be an uphill battle filled with disappointment a lot of the time, but we’re still enthusiastic voters.”

Steve Watson said he does find political advertising exhausting, however.

“I do get sick of it, but it’s part of the game,” he said. “It’s always that way. What I do hate is the dark money coming in. No transparency. Citizens United screwed that up for everybody, so now money is coming in from everywhere.”

Cooper acknowledges that having city elections so soon after the midterms might lead to low turnout. But, in his eyes, the issues he and his constituents care about provide a reason for people to stay engaged. And he believes that the voters of Ward 2 understand they have to keep showing up, even when it’s tiring.

“They understand that you have to create these initiatives, these accountability measures. That’s a step. Now they know the next step is about protecting and implementing them,” Cooper said. “You can’t be fatigued on that. Democracy requires consistent showing up, and in Ward 2 we show up. So maybe there is some fatigue out there from voters, but that’s why I’m campaigning.”