A bill recently signed into law will allow Oklahoma property owners to repudiate discriminatory language within land records by filing a declaration with their county clerk.

Authored by four members of the House of Representatives and three senators, HB 2288 was signed May 22 by Gov. Kevin Stitt and will become effective Nov. 1.

The bill’s lead author, Rep. John Pfeiffer, said he read a NonDoc article in July about a Black Edmond businessman who came across a racially restrictive covenant on his business property’s plat.

“I read the article. Parts of it made me mad about the state, and I thought, well, we can fix it,” said Pfeiffer (R-Orlando).

Although a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court decision declared such language unconstitutional and unenforceable, many land documents created under segregation still state that only Caucasians are allowed to own certain property. Some states have created processes to remove or repudiate those discriminatory covenants, with Oklahoma being the most recent.

Once the law takes effect Nov. 1, Oklahoma property owners may file a declaration with their county clerk stating that any discriminatory language in their property’s plat or abstract is “extinguished and severed from the recorded real estate conveyance or instrument.”

Upon filing the declaration, a repudiation document stating the referenced discriminatory covenants are null and void will be included within public land records related to the subject property.

The Oklahoma Land Title Association was involved in conversations surrounding how best to address racist language in land records.

“HB 2288 allows property owners the simplest and most economical way to renounce these old discriminatory covenants by publicly asserting their repudiation of these illegal and unconstitutional restrictions,” said J.T. Beard, president of the Oklahoma Land Title Association. “This new law provides a practical approach to eliminate those restrictions and continue to defend private property rights without putting an immense burden on the public recorders or unnecessary costs to consumers.”

With HB 2288, Oklahoma joins several states that have created pathways for property owners to address racist language in land records, including deeds, abstracts and other documents. Those states include Texas, Florida, California and Indiana.

“Oklahoma is a leader among other states who are struggling to find effective solutions by the adoption of its ‘recorded repudiation’ approach in HB 2288, which permits a homeowner to record a new document in the public records, indeed in the current chain of title, that provides notice to the world that the discriminatory and obnoxious restrictive covenant is unenforceable,” Beard said.

Pfeiffer stated on the House floor May 16 that he and other legislators worked with real estate agents, abstractors and county clerks “to clear this up to make sure we have a way to get rid of discriminatory language out of covenants and conveyances.”

While the language will remain in official land records maintained by county clerks, filing a declaration will allow future copies of deeds, plats or abstracts to be reprinted without the discriminatory language, Pfeiffer told NonDoc.

“Once you have that declaration in there, future copies, they don’t have to have that language in there,” Pfeiffer said. “The official land deed at the courthouse has that paper, and then any time you get a copy, they don’t have to copy it over because there is a declaration in the official paper.”

According to HB 2288, the property owner may file such a declaration:

1. Prior to recordation of a deed conveying real property to a purchaser; or

2. When such real property owner discovers that such discriminatory restrictive covenants exist.

In the prescribed declaration, property owners must list the name of the county where the property is located, the date of the instrument containing the discriminatory restrictive covenant, the instrument type — such as a deed or abstract — and other information about where the instrument is recorded.

Reps. Daniel Pae (R-Lawton), Eric Roberts (R-OKC), Cyndi Munson (D-OKC), and Sens. Brent Howard (R-Altus), Joe Newhouse (R-Tulsa) and George Young (D-OKC) co-authored the measure.

Pfeiffer praised those who helped push the bill through to the governor’s desk.

“I just want to say a thank you to the county clerks who helped me work through some of the issues and the Oklahoma REALTORS Association who helped lobby the bill because they wanted to see this stuff fixed,” Pfeiffer said. “And thank you [NonDoc] for writing the story and bringing this up and bringing it to our attention that something needed to be done about this.”

Frost: ‘I can say something to help make a difference’

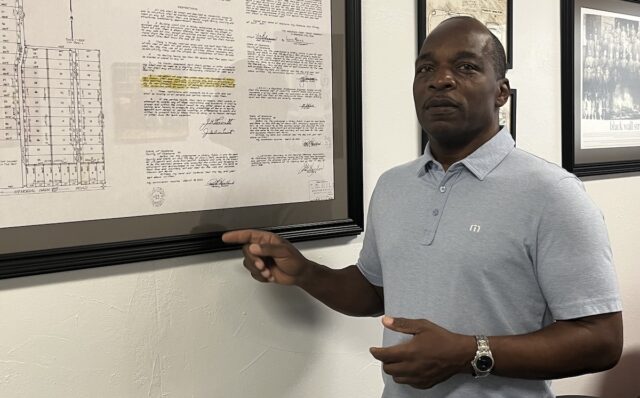

Wayne Frost, a Black business owner in Edmond, found a racially restrictive covenant on his own property’s plat while seeking to expand his auto accessory business in 2021. Frost’s story ultimately led to Pfeiffer’s bill.

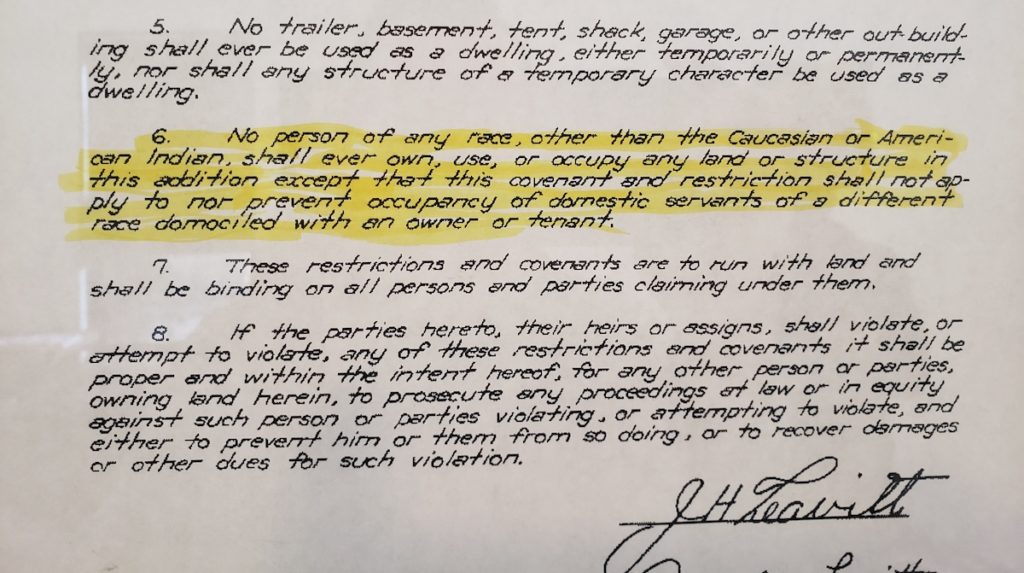

Restriction No. 6 of the Leavitt’s North Park Addition plat reads:

No person of any race, other than the Caucasian or American Indian shall ever own, use, or occupy any land or structure in this addition except that this covenant and restriction shall not apply to nor prevent occupancy of domestic servants of a different race domociled (sic) with an owner or tenant.

“That language really offended me,” Frost said. “It offends me, and it should offend anybody of any race that’s being excluded only because the color of their skin.”

When Frost first purchased his property at 4646 Rhode Island Ave. in Edmond and picked up the plat language, he said he didn’t read it. Frost found the discriminatory language when purchasing the abutting lot behind his business in 2020 with plans to expand his business.

Frost said he asked a receptionist at the Oklahoma County Clerk’s Office whether the language could prevent his planned business expansion. While Frost was assured the covenant was unenforceable, the racially restrictive language discouraged him.

“I personally think it should be eradicated from all covenants in any neighborhood that still harbors that offensive language,” Frost said.

Ultimately, Frost decided to highlight the racially restrictive covenant and hang the document on the wall of a lounge room within his business.

“It symbolizes two different things,” he said. “The first thing it symbolized is where Edmond was and where our country was at that time. To have that to remind me where we are today — even though it’s still on the books — it gave me a driving force to try and do something about it.”

Frost said hanging the plat in his business kept the language on his mind.

“It reminded me every day when I walk into the office, if I can talk to somebody, if I can say something to help make a difference — that would just keep motivating me to keep it in the forefront of my thoughts to just help make a change for the city of Edmond and the state of Oklahoma,” Frost said. “If I could get somebody to listen to me, then my job is done.”

Frost said he intends to file a declaration at the Oklahoma County Clerk’s office Nov. 1.

“To have this transpire — this new legislation — it will definitely give me peace of mind knowing going forward that any time I buy property, I won’t have to worry about seeing that type of language which will definitely intimidate me,” Frost said. “It means a great deal knowing that we are as a state working towards the inclusion and diversity of all people. That means a lot to me being an African American.”

‘A reminder of Edmond’s past’

When the Leavitt’s North Park Addition subdivision was platted in 1947, Edmond was widely recognized as a sundown town, meaning Black people faced intimidation and threats for being visible in the community after sunset. A number of Oklahoma towns, such as Norman, were considered sundown towns for much of the 20th century. Racially restrictive covenants were included in many housing additions across Oklahoma and throughout the country.

Edmond’s first housing addition platted with a racially restrictive covenant was the Highland Park Addition in 1907. Excluding the Edmond Highway Addition in 1924, every neighborhood platted in Edmond from 1911 until 1949 contained a racially restrictive covenant.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that enforcement of discriminatory covenants based on race violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

When President Lyndon Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act on April 11, 1968, that legal precedent was codified into law.

Oklahoma County property records: Click here.

Frost, who relocated from southeast Oklahoma in 1977, said he remembers seeing an old, faded sign east of Interstate 35 near Arcadia stating, “Sundown town.”

“So, when people were leaving Arcadia from the east heading to the west to get into Edmond city limits, it was still a reminder of Edmond’s past,” Frost said.

In its 2023 legislative agenda, the Edmond City Council outlined its support for legislation that allowed “for expungement of discriminatory restrictive covenants from public land records.”

Edmond Mayor Darrell Davis, who became Edmond’s first Black mayor when he was elected in 2021, praised the legislation passed this session at the State Capitol.

“The signing of HB 2288 is a step in the right direction of correcting the historical discriminatory language of our past that prevented African Americans and other ethnic groups from having the ability to live where they wanted to live and own property,” Davis said. “I am appreciative that property owners can now take legal steps to have this language removed from their property records.”

In a press release, Oklahoma Association of REALTORS President Julie Smith celebrated HB 2288 and thanked legislators as well as Davis for advocating for the bill.

“Oklahoma REALTORS have been at the forefront of the drive for HB 2288’s passage,” Smith said. “This victory is a tremendous milestone for Oklahoma and is a significant stride toward fairer housing in our state.”