For leaders of the Kialegee Tribal Town and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, Wednesday’s meeting of a rarely convened committee of the Oklahoma Legislature felt like another tough draw from a deck of political and bureaucratic cards long stacked against them.

After nearly an hour of discussion with Gov. Kevin Stitt’s general counsel, the Joint Committee on State-Tribal Relations unanimously disapproved a pair of Stitt-negotiated casino gambling compacts with the two smaller tribes, whose officials were not offered the opportunity to speak about their goals, needs and concerns.

“We are disappointed that we didn’t get to tell our side of the story,” United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians Chief Joe Bunch said after the meeting. “Today’s defeat, it hurt. It hurts big, particularly not to have the opportunity to discuss these issues.”

Mekko Stephanie Yahola, the leader of the Kialegee Tribal Town based just west of Wetumka, offered a similar assessment.

“I’m kind of disappointed how the bigger tribes have tried to keep the smaller tribes down,” Yahola said, referencing historic opposition to KTT gaming by the associated Muscogee Nation and opposition to UKB gaming by the larger Cherokee Nation. “We were kind of disappointed that we were not able to speak at that table and give our side of the story.”

Stitt, who has clashed with the state’s largest tribal nations over gaming compact terms and other state-tribal agreements, said he has tried to negotiate new gaming compacts with smaller tribes to provide them economic opportunities while also establishing higher payment percentages and audit requirements for the state.

“They are some of the poorest tribes in our state,” Stitt said as Yahola and Bunch nodded. “Some of the smallest.”

Senate Floor Leader Greg McCortney, who made both motions to disapprove the KTT and UKB compacts, said after the meeting he didn’t know why the tribes’ leaders were not asked questions about their compact negotiations, even when Stitt’s general counsel — Trevor Pemberton — said they would be in a better position to discuss their casino plans than he was.

McCortney (R-Ada) said he had the “vaguest sense” of the history and political dynamics of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, which is one of three federally recognized Cherokee tribes.

“I do not know the history of their tribe and the tribal lands. The fact that they don’t have any, I would need a lot more information about how we got here,” McCortney said, appearing not to know the UKB has 76 acres of land held in federal trust for non-gaming purposes.

Sen. Brent Howard (R-Altus) served as co-chairman of Wednesday’s meeting. Asked why legislators did not hear from or ask questions of the tribal leaders to learn about their history and current situations, Howard called it “a little bit of oversight.”

“It didn’t really come up as to that specific side. The request for consideration and the push really did come more from the governor’s office,” Howard said.

After 3 years and 180 filings, compact litigation lingers

On Sept. 14, Stitt, Bunch and Yahola signed and sent letters to leaders of the Oklahoma Legislature asking that the Joint Committee on State-Tribal Relations meet to consider Stitt’s gaming compacts with the Kialegee Tribal Town and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians.

Originally signed by Stitt and KTT and UKB leaders in 2020, the two compacts rejected by the Legislature on Wednesday are among four new agreements Stitt signed and submitted that year to the U.S. Department of the Interior, which reviews gaming compacts for compliance under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988. In June 2020, the agency deemed a pair of Stitt’s new compacts with the Otoe-Missouria Tribe and the Comanche Nation to be approved by choosing neither to reject them nor affirmatively approve them. The federal agency did the same for the KTT and UKB compacts.

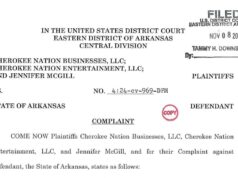

The new compacts triggered state and federal litigation, with leaders of the Oklahoma Legislature suing Stitt for circumventing legislative approval. Then, four larger tribes sued in protest of the federal approval.

In August 2020, the Chickasaw, Cherokee, Choctaw and Citizen Pottawatomi nations sued the UKB, KTT, Otoe-Missouria Tribe, Comanche Nation, Stitt and the U.S. Department of the Interior. The larger tribes have argued that the federal agency erred in deeming the compacts approved because the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled that Stitt had not sought required legislative approval and that the Otoe-Missouria and Comanche compacts included sports betting provisions not authorized in state law.

Three years later, the case has seen more than 180 filings and remains pending in U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Believing he should take over representation of the state of Oklahoma’s interests, new Attorney General Gentner Drummond entered an appearance this summer. He said Stitt’s expensive use of private attorneys to defend the lawsuit is a mistake and that the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s rulings prove the four smaller tribes’ new compacts are improper.

Members of Stitt’s legal team and staff have opposed Drummond’s involvement, alleging that Drummond has undue allegiance to leaders of the large tribes and pointing to a political donation he made to the chief of the Cherokee Nation, which is the case’s lead plaintiff. Stitt also argues that he has a right to choose his own attorneys to represent his office in court.

Most recently, Drummond has asked the federal court to answer and certify a question of law to the Oklahoma Supreme Court:

Whether the Oklahoma Attorney General can take and assume control of the prosecution or defense of Oklahoma’s interests in any action, including where the Oklahoma Governor is a named party, in his or her official capacity, and where the Oklahoma Governor has previously employed counsel?

Responding to Drummond, Stitt’s attorneys told the federal court that the attorney general’s latest motion is “another political sideshow.”

“As the court knows, it has not yet ruled on the attorney general’s unauthorized notice of appearance on behalf of the governor,” Stitt’s lawyers wrote in response. “At present, the attorney general is not a party to this litigation, and the governor (who is a party) says that the attorney general is not his chosen counsel. The attorney general accordingly has no more standing to file a motion demanding relief than any other non-party.”

Drummond also made his feelings known to members of the Oklahoma Legislature’s Joint Committee on State-Tribal Relations ahead of Wednesday’s meeting. In a hand-delivered letter sent Monday, Drummond argued that the KTT and UKB gaming compacts were illegal.

“Proper respect for the law compels the conclusion that the Joint Committee lacks authority to make valid that which the Oklahoma Supreme Court earlier declared to be invalid,” Drummond wrote.

Pemberton pushed back Wednesday, saying Drummond’s letter appeared to conflate elements of the Supreme Court’s decision about the Otoe-Missouria and Comanche Nation compacts with the majority opinion in the case regarding the KTT and UKB compacts.

“The Supreme Court did not find the compacts to be forever invalid, and that is effectively the overarching position of the attorney general. The Supreme Court held (…) ‘without proper approval by the joint committee, the new tribal gaming compacts are invalid under Oklahoma law,'” Pemberton said. “So once they are approved by the joint committee, they would, in effect, be valid under Oklahoma law.”

Drummond argued that the exact sequence of gaming compact approval actions matters between state and federal reviews. Pemberton said no such requirement exists in law, although he pledged that he and Stitt would resubmit the KTT and UKB compacts to the Department of the Interior if the joint committee approved them.

Some committee members asked questions that emphasized Pemberton was not the governor’s general counsel in 2020 when the new compacts were signed, submitted and subjected to litigation. Pemberton, who said he was “minding my own business at the court” in 2020, had been a Court of Civil Appeals judge when Stitt hired him as general counsel in October 2021.

Making subtle reference to many legislators’ frustration with how Stitt has previously tried to circumvent legislative approval on various topics, Rep. Kevin Wallace, who served as co-chairman of the Joint Committee on Wednesday, pointed Pemberton to the penultimate page of Stitt’s compacts with the KTT and UKB.

“This compact, when signed by the governor of the state of Oklahoma, is approved by the state of Oklahoma,” Wallace (R-Wellston) read aloud from the documents. “No further action by the state or any state official is necessary for this compact to take effect upon approval by the secretary of the interior.”

Pemberton told lawmakers that he was making sure the compacts were before them for consideration.

“Following the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s guidance in this context, that is why we have submitted it here,” he said.

Wallace concluded his questions with further reference to the Legislature’s lingering frustrations with Stitt.

“Would you agree there are three co-equal branches of government?” Wallace asked.

Pemberton replied, “Without a doubt.”

A long, complicated history

Wednesday’s committee meeting and its associated letters and legal filings underscore the complex nature of American Indian law, as well as the complicated relationships among 38 federally recognized tribal nations currently headquartered in Oklahoma.

Despite a massive multi-year advertising campaign that proclaims tribal governments are “United For Oklahoma,” historic differences have caused protracted legal battles and generational disputes. On a macro level, many of the complexities and tensions stem from the Indian Removal Act — passed by Congress and signed into law by President Andrew Jackson in 1830 — and subsequent elements of attempted genocide and forced assimilation pushed by the U.S. government.

In a modern context, the specific situations facing tribes like the UKB and KTT are not widely known among non-tribal residents of Oklahoma. For instance, UKB membership requires a one-quarter blood quantum but is not based on the Dawes Rolls. Asked Wednesday if he would elaborate on his “vaguest sense” of UKB history, McCortney replied, “I’m not going to answer that question.”

Throughout Wednesday’s hearing of the Joint Committee on State-Tribal Relations, legislators repeatedly apologized for their uncertainty in how to say the two tribes’ names. Just as Stitt awkwardly did during a 2019 press conference, Howard mispronounced “Keetoowah.” Others tried unsuccessfully to recall details of how the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma received approval to build Golden Mesa Casino, which is located near the Panhandle city of Guymon and is operated by the Chickasaw Nation’s Global Gaming Solutions company.

During a press availability with Stitt and Yahola after Wednesday’s meeting, Bunch was asked by a reporter to spell his name. Underscoring an earlier statement about the prevalence of UKB members who still speak their historic language, Bunch stated his name in Cherokee.

“The UKB broke away from the Cherokee Nation in 1859, prior to the Civil War,” Bunch said, noting that the UKB, the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians — based in North Carolina — are the three tribal nations of the Cherokee people. “We were not slave owners or anything of that nature. We fought with the north. We even have flags to that effect.”

Bunch and UKB Assistant Chief Jeff Wacoche said their tribe’s economic opportunities have been greatly limited without current authorization to operate a casino. Originally opened in 1986 — two years before the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act — the UKB’s historic casino stood on the south side of Tahlequah.

Only the sign stands on the property now after a lengthy legal battle waged by the Cherokee Nation, which challenged the UKB’s right to place land into trust with the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs for either operating a gaming facility or providing tribal services. During the court case, the Cherokee Nation argued that the UKB did not meet the definition of “Indian” under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. But Congress recognized the UKB in 1946 under the terms of the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936, which said properly chartered tribes like the UKB “enjoy any other rights or privileges secured to an organized Indian tribe.”

In 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit ultimately found in favor of the UKB, saying the Department of the Interior — which administers the BIA — made a proper decision in 2011 when it approved placing 76 acres of land in Tahlequah into trust for development of cultural grounds, an elder center, a museum and other community services.

Now, the UKB is awaiting the Department of the Interior to take action on its application to place the 2.6 acre-site of its former casino into trust, something the federal agency does “to help tribes regain lost lands and promote tribal self-determination.”

“We’re still waiting on the ruling on that,” Wacoche said Wednesday. “They told us 16 months, and 16 months is up in December, so we’re hoping that any time now we should be getting a ruling on that.”

The UKB’s controversial compact with Stitt, however, describes a proposed “Logan County facility,” which Wacoche said has been under discussion with leaders in the city of Guthrie.

“They were looking forward to working with us,” Wacoche said, adding that the UKB have been speaking with “big-time, huge players in casinos who were going to bring a huge resort to that area.”

While a Logan County casino would offer the UKB a gaming facility beyond the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation Reservation boundaries, its concept raised questions for some lawmakers who expressed concern about such a development in the “unassigned lands” of a state that already features more than 125 tribal casino locations.

The same concern hampered consideration of the Kialegee Tribal Town compact, which referenced a potential casino east of Choctaw Road in Oklahoma County. Currently, the state-owned and Chickasaw-operated Remington Park stands as the only casino in Oklahoma, Cleveland or Logan counties.

“I’m an Oklahoma County guy,” House Majority Floor Leader Jon Echols (R-OKC) told Pemberton during Wednesday’s hearing. “My understanding is that the traditional tribal boundaries of the Kialegee Tribal Town does not include Oklahoma County.”

Pemberton replied, “That is certainly my understanding, and the Kialegee could address that better than I can.”

Nonetheless, neither Yahola nor KTT Second Warrior Gina Powell were granted the opportunity to discuss their tribe, which has fewer than 400 members. KTT members are also citizens of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, which originally was a confederacy of towns that sent representatives to the House of Warriors and House of Kings.

After congressional passage of the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936, some towns applied for and received federal recognition. Currently, three federally recognized “tribal towns” exist within and in connection to the Muscogee Nation: the Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, the Kialegee Tribal Town and the Alabama Quassarte Tribal Town. (The Sapulpa-based Euchee Tribe has unsuccessfully sought similar status with the federal government.)

The Muscogee Nation reorganized and achieved federal recognition under the OIWA in 1970, subsequently adopting a new constitution in 1979. The Muscogee Nation still features more than a dozen active ceremonial grounds within its reservation boundaries, but the majority do not have “tribal town” status with governmental structures like the Kialegee.

“We are the grandfathers of the Muscogee Nation,” Yahola said Wednesday.

Howard, the Senate chairman of the joint committee, said after the meeting that he would support the UKB ultimately obtaining a gaming compact and a casino location.

“I think that they should be granted their lands, and then the determination should be what they were promised as far as part of treaties or moving here from the federal government,” Howard said. “That should be established first so they have their actual land that is in trust and then we move forward from that point negotiating the compacts, whether that is one of the model compacts or one that’s negotiated separately.”

Wacoche: Political contributions play ‘the major role’

Seated with Stitt in the governor’s conference room of the State Capitol, the four assembled leaders of the UKB and KTT told media that they believe the state’s largest tribes have used their economic advantages to gain political power to the detriment of some smaller tribes.

“The bigger tribes, they always say it: ‘If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu,'” Wacoche said. “We always seem to be on the menu.”

Bunch, Wacoche, Yahola and Powell each answered affirmatively when asked whether larger tribes’ significant campaign donations to Oklahoma politicians have yielded undue influence over matters like UKB and KTT gaming desires.

“I think that’s the major role right there,” Wacoche said. “We’re not able to generate these dollars that others are able to put through these campaign contributions.”

Beyond campaign donations made by individuals, Oklahoma Ethics Commission records chronicle campaign donations made directly by tribal nations to Oklahoma candidates. While IGRA specifies five types of expenditures for gaming-generated dollars, political contributions are generally considered beyond those boundaries. Still, since 2018, the state’s largest tribal governments have managed to donate more than $4 million to candidate committees and legislative PACs, a figure that does not include millions more donated to super PACs and dark money efforts.

Sorted by amount, the Chickasaw Nation, Cherokee Nation and Choctaw Nation have made the largest tribal contributions to political action committees that report to the Oklahoma Ethics Commission. The largest recipient of tribal dollars since 2018 has been the House Republican Caucus’s Majority Fund. During that time, the Chickasaw Nation has donated $950,000 to the PAC. The House GOP Majority Fund received $250,000 from the Cherokee Nation in 2022 and a pair of $50,000 contributions from the Choctaw Nation in 2018 and 2020.

In 2022, records indicate the House GOP Majority Fund raised more than $1.08 million, with $750,000 combined coming from the Chickasaw Nation and Cherokee Nation governments, not including individual contributors.

“The Oklahoma Republican House Majority Fund has been a great fundraiser. We’ve passed the bills and the issues that citizens care about,” Echols said about the donatins. “I can tell you that I don’t know personally many dollars have been given from any entity, but I can tell you dollars never influence votes.”

In late 2018, less than two years before they would sue Stitt and the Department of the Interior over his new gaming compact efforts, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Citizen Pottawatomi nations donated a combined $210,000 to the Oklahoma Turnaround Fund, which was the PAC formed to support Stitt’s inaugural events after his initial election. When Stitt ran for reelection four years later, leaders of those tribes supported his opponent.

“They just seem to have people in the right places. They have folks working in the Department of the Interior, they have folks working here in the State Capitol,” Wacoche said. “It’s everywhere. The regional director of the BIA in our area, he’s a Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma citizen, and whenever we did get our land in trust, he abstained and stepped down. He wouldn’t even sign our land-in-trust deed.

“It’s so obvious it’s there. It’s very clear.”

Stitt, a Cherokee Nation citizen whose disputes with his own tribe led to him being lampooned during a clown dance at this year’s powwow, said the UKB and KTT deserve economic opportunities derived from casino gaming.

“It’s just really weird why these guys aren’t allowed to game and others can,” Stitt said. “So the question to me is why in the world would the Legislature decline agreement where these guys can game just like everybody else?”

Stitt noted that the exclusivity fee rates — percentages of gaming revenues paid to the state for exclusive casino rights — in his compacts with the UKB and KTT are more than twice as high as the 4 percent to 10 percent rates specified in the state’s current Model Tribal Gaming Compact.

“If every casino was on this compact or this agreement or this (exclusivity fee) rate, it would be worth more than double (for Oklahoma),” Stitt said.

Cherokee Nation Attorney General Chad Harsha said in a statement that the legislative committee’s decision Wednesday was positive.

“Thankfully, the Senate’s Joint Committee on State-Tribal Relations did not pass the governor’s proposed compacts with UKB and Kialegee, which were previously held to be invalid by the Oklahoma Supreme Court,” Harsha said. “Hopefully the governor will move on from his quest to divide and will work with tribal/state partners on good faith compacting negotiations in the future.”

Muscogee Nation Principal Chief David Hill agreed.

“These compacts were political stunts from the governor meant to divide and conquer tribes,” Hill said. “It’s good to see that Attorney General Gentner Drummond and this panel would rather follow the law.”

Read AG Drummond’s letter to state-tribal relations committee

https://nondoc.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/10-25-23-AG-Gaming-Agreement-w-Kialegee-and-Keetoowah-10.23.2023.pdf” viewer=”google”](Correction: This article was updated at 2:25 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 26, to reflect the formal name of the Cherokee Nation. It was updated again at 5:05 p.m. to correct reference to Trevor Pemberton’s previous job.)