An attempted class-action lawsuit accusing OG&E of fraudulent collection of electric utility franchise fees from Norman residents was dismissed today by Cleveland County District Judge Thad Balkman, who said the Oklahoma Supreme Court addressed such situations in a 1945 case.

Former Norman City Councilwoman Alison Petrone and her husband, Aaron, filed the lawsuit Oct. 12 and alleged that OG&E has improperly collected a 3 percent franchise fee on the electric bills of its Norman customers. The city’s franchise agreement with the company expired in 2018 and was subsequently rejected by voters in January 2023, with 60.7 percent of those casting ballots opposing the OG&E renewal.

“This franchise clearly expired, and for whatever reason, OG&E took steps not to renew it,” the Petrones’ attorney, Brad Barron, argued to Balkman on Thursday. “We allege that the reason they did not take those steps is because they believed it would fail. And it turns out their intuition was right. It did go to a vote of the people in January 2023, and it failed.”

OG&E filed a motion to dismiss the Petrones’ lawsuit Nov. 6, and Stratton Taylor argued the publicly traded utility’s position Thursday.

“They want to make a claim for unjust enrichment. But we don’t have the money. We never stood to have the money,” Taylor told Balkman. “The franchise and the implied contract and the Oklahoma Corporation Commission says OG&E collects on behalf of the city of Norman from the consumers (…) and then gives the money to the City of Norman so that OG&E has access to city streets and alleyways for the purpose of providing electricity to the citizens of Norman, the businesses, the hospitals, etc.”

Balkman agreed with Taylor’s arguments and referenced the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s decision in Town of Pittsburg v. Cochran, which held that “an implied contract of indefinite duration arises and the company functions as a quasi-public utility subject to the terms of the former franchise and the rules and regulations of the Corporation Commission.”

“While the constitution is vague in the sense that it doesn’t talk about what happens when a franchise agreement expires, the Supreme Court addressed this in the case that was just mentioned,” Balkman said.

Barron said after Thursday’s hearing that the Petrones were “assessing all of their options” and had yet to decide whether to appeal Balkman’s ruling.

“I think what is most disappointing about today’s result is that it ignores the will of the people of the city of Norman,” Barron said. “The people of the city of Norman have one way to control the provision of electricity, and that is through voting and approving a franchise agreement. And here there was no franchise agreement for several years, and when it was presented to the city, it was rejected, and I think that’s unfortunate.”

Aaron Cooper, OG&E’s manager of corporate communications, said the company appreciated Balkman’s decision.

“We will continue serving our customers in Norman and providing them reliable electricity that energizes their homes and businesses,” he said. “We look forward to Norman residents having the opportunity to approve a new franchise agreement with OG&E on the March 5 ballot.”

‘We are working now in an area that hasn’t happened’

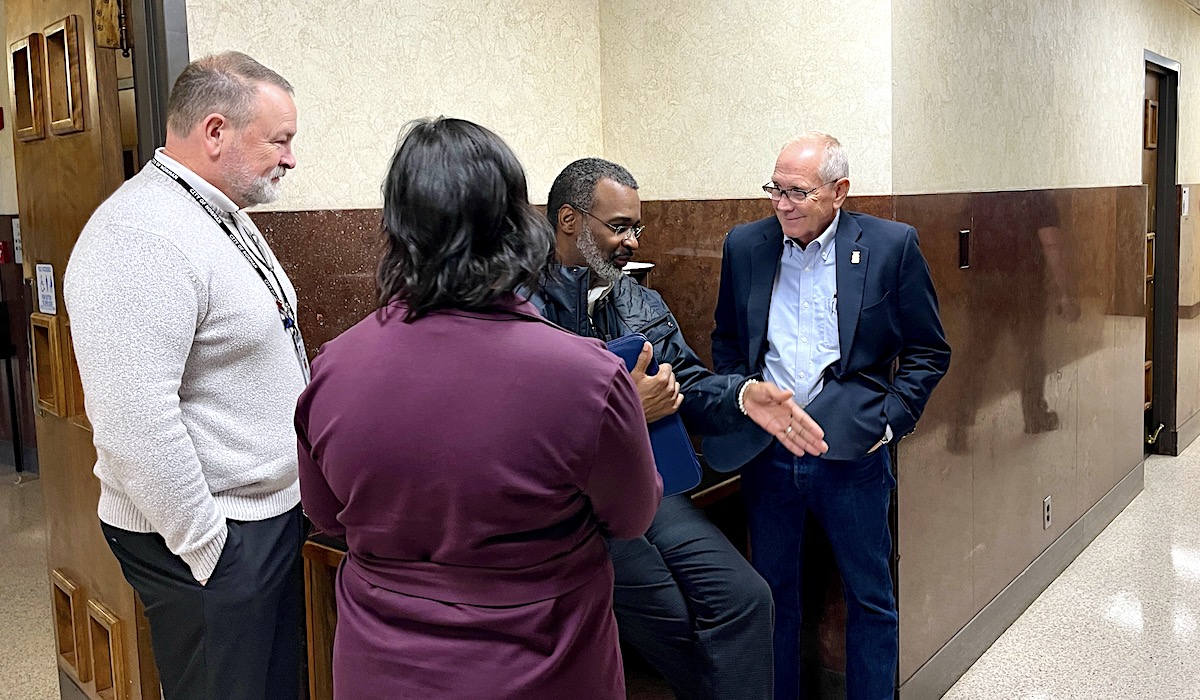

Seated in the front row of Balkman’s courtroom Thursday were Norman Mayor Larry Heikkila and top city administrators. After the case was dismissed, Heikkila said he was “pleased.”

“It was well-argued on both sides. Judge Balkman is going to make a good decision, and life is good,” he said. “This is the way it should work.”

Norman’s franchise agreement with OG&E expired in 2018, leaving the city without a formal agreement with the utility provider. But for customers, not much changed, even after voters rejected the 2023 proposal, which included the company providing free electricity for traffic lights and municipal buildings. OG&E has continued to provide power to city residents and businesses for five years, and customers paid a 3 percent line-item fee on their electric bills just as they had before.

The Petrones argued in their petition that “without a valid, voter-approved franchise agreement, the electric utility has no right to charge citizens of a municipality a franchise fee.” They wrote that Norman residents have expressed preferences to OG&E about things like renewable energy and how tree limbs and vegetation are cleared near power lines, a concern that recently drew OG&E significant criticism in Edmond.

During Alison Petrone’s tenure in elected office, the Norman City Council voted in 2019 to transition fully to wind and solar or other forms of renewable clean energy in city buildings by 2035. But more than 60 percent of voters opposed renewing Norman’s OG&E franchise agreement in January 2023.

Heikkila said Norman residents will again have a chance to vote on an OG&E franchise agreement March 5.

“There’s been an initiative petition put in, and we’re ready to go March 5. It’s going to be Super Tuesday. And then people will say what they want, and if they decide to say ‘No,’ well — I don’t know,” Heikkila said with a laugh. “We are working now in an area that hasn’t happened. We had never lost a franchise agreement before.”

Franchise agreements for electric and gas utilities come up for election all around Oklahoma, with most communities broadly passing the proposals. In rural towns, votes are sometimes unanimous in favor.

Recently, however, Norman has been a different story. A 25-year extension of an Oklahoma Natural Gas franchise agreement went before Norman voters in September and narrowly passed with 50.2 percent support.

Asked what Norman would do if the OG&E agreement fails again in March, Heikkila replied, “We’ll go on advice of counsel.”

Norman City Attorney Kathryn Walker was standing near the mayor and offered her advice: “Let’s not comment.”

‘There has to be electricity provided’

During Thursday’s hearing, Balkman asked Taylor an obvious question about the practical implications of an “implied contract” existing in perpetuity after a vote fails.

“Why would a utility provider ever bring a franchise agreement to a vote of the people if you can just have this implied contract go on indefinitely?” Balkman asked.

Taylor noted that “there has to be electricity provided.”

“Frankly, electricity and electric providers are fairly competitive,” Taylor said, noting that electric cooperatives or other utilities could approach the Norman City Council about providing service instead of OG&E. “If they’re invited, they’re probably going to make a pitch to the council and say, ‘If you want somebody to leave, we will come.’ And that is an option, but that has not occurred here.”

Functionally, however, that is rarely a workable option in Oklahoma. A moratorium on municipalities’ ability to use eminent domain to obtain electric lines and power poles was created in 1998 by the Legislature as a provision of SB 888. Taylor, who was president pro tempore of the Senate that year, voted for the omnibus utility bill, which passed the Senate 43-1 during the final week of session.

Over the years, the law has become a major point of contention for some current legislators, who would like to see it repealed so cities and towns in their districts could have more flexibility when it comes to electricity provision. The major electric utilities in Oklahoma, OG&E and PSO-AEP, have supported the moratorium as a legal protection for their infrastructure investments.

As the law stands, if the Norman City Council wanted to transition its OG&E customers to another company, the three entities would need to strike an agreement for OG&E to sell its infrastructure, or the new company would have to install its own power grid.