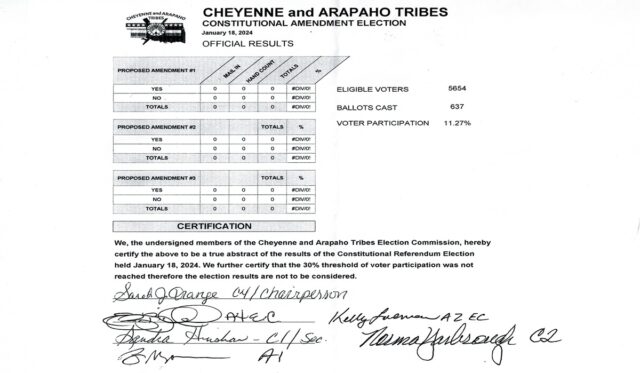

Three proposed constitutional amendments failed Thursday after only 11.3 percent of Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes voters mailed back ballots for the proposals, which would have broadened the candidate base for executive and legislative offices.

Because the tribes’ proposed constitutional amendments require at least 30 percent voter participation to be counted in a special election, the 637 ballots submitted by Thursday’s deadline “are not to be considered,” according to the official certification signed by the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Election Commission.

“In order for the amendments to pass, 30 percent of the total registered voters would need to participate in the special election,” read a statement provided by Rosemary Stephens, the tribes’ public information director and editor of the Tribal Tribune. “Out of the 5,654 ballots mailed out to eligible registered voters, only 637 ballots were returned. A voter participation of 11.27 percent.”

The three proposed amendments would have:

- Allowed tribal citizens to seek the offices of governor and lieutenant governor regardless of where they live, requiring only that they move within tribal boundaries after winning election;

- Allowed tribal citizens to seek legislative offices regardless of where they live, requiring only that they move within their specific legislative district after winning election;

- Created an at-large legislative district, requiring that candidates live outside of any legislative district.

Thursday’s low turnout doomed the proposals, underscoring concerns about voter participation that some tribal leaders sought to address by broadening candidate eligibility requirements. It’s also unclear how robustly tribal citizens were aware of Thursday’s election.

Beyond ballots being mailed to all registered voters, the only other notice most voters received was an article in the Tribal Tribune published in both December editions of the paper and a vague “vote yes” ad in first edition of the new year.

“The proposal needed more information and maybe people didn’t understand it totally,” Gov. Reggie Wassana said. “The authors of the resolutions put it up for a vote through passage at the annual Tribal Council meeting. The low turnout may have been (due) to the lack of clarity that most had questions with.”

Wassana also pointed to other issues with the proposals, such as only one at-large district being proposed instead of two. All other legislative districts for the tribes have two representatives: one Cheyenne and one Arapaho. Some voters may also have been concerned with allowing out-of-district candidates file for office.

Tribal Council set proposals for special election

Proposed amendments one through three were passed by the Tribal Council on Oct. 7, and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Election Commission scheduled a special election to approve or reject the constitutional amendments for Thursday.

RELATED

Gov. Reggie Wassana: ‘Times are changing’ on blood quantum by Joe Tomlinson

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes’ Tribal Council is not the legislative branch of the tribes’ government. Under the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes’ constitution, the government is divided into four branches: the Tribal Council, the legislative, the executive and the judiciary.

The Tribal Council consists of every member of the tribe over 18 years old, and whoever attends its meetings can vote. It meets annually on the first Saturday of October, and 75 citizens are required for a quorum. The number of eligible members of the Tribal Council was expanded in 2021 when tribal citizens voted to lower the blood quantum requirement for citizenship from one-fourth to one-eighth.

Tribe elected legislators, election commissioners in November

Between last year’s October Tribal Council meeting and Thursday’s special election, Cheyenne and Arapaho citizens elected four tribal legislators and four election commissioners.

Two incumbents for the election commission were reelected without an opponent: Norma Yarbrough, representing Cheyenne District 2, and Sarah Orange, representing Cheyenne District 4.

Arapaho District 1 Election Commissioner Ray Mosqueda won reelection with 61.43 percent of the vote, defeating Kennesha Willis (38.57 percent) in the November election. In Arapaho’s District 2, Kelly Loneman won 63.64 percent of the vote to unseat incumbent Dale Hamilton Jr., who garnered 36.36 percent support.

In the four legislative elections, all three incumbents who ran were reelected:

- Travis Ruiz (Arapaho District 3) won 54.29 percent of the vote, while Alfred Whiteshirt garnered 45.71 percent;

- Rector Candy (Arapaho District 4) won 55.56 percent of the vote, while Reva Wassana garnered 44.44 percent;

- Bruce Whiteman Jr. (Cheyenne District 1) won 60.32 percent of the vote, while Wilma Blackbear garnered 39.68 percent.

In the open Cheyenne District 3, Thomas Trout was elected to a first term in the Legislature with 54.73 percent of the vote, to Charlene Wassana’s 45.27 percent.

Death of Lt. Gov. Miles leads to appointment of Hershel Gorham

The position of Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes lieutenant governor became vacant after the Sept. 4 death of Lt. Gov. Gilbert LaMott Miles. He was first elected as lieutenant governor in 2017 and reelected in 2021. He was the first Cheyenne and Arapaho lieutenant governor to serve two consecutive terms after the passage of the 2006 constitution. Before constitutional amendments were made in 2006, the nation was overseen by a business committee.

Gov. Reggie Wassana appointed his general counsel, Hershel Gorham, to complete the rest of Miles’ term, which expires in 2025. Gorham had served as general counsel since January 2018. He also serves as ex-officio director of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Community Development Corporation.

Gorham and the newly elected officials were sworn in during a ceremony Jan. 6.

Formal reservation disestablished, but informal reservation growing

While the landmark decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma found the Muscogee Nation Reservation was never disestablished and later decisions have upheld the reservation status of several tribes in eastern Oklahoma, tribes in western Oklahoma have been less successful in having their historic reservations recognized. In December 2022, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals held that the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation was disestablished by Congress in 1891.

The disestablishment and allotment of the reservation predates Oklahoma statehood and highlights the different histories of tribes in Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory. On April 19, 1892, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation was opened for settlers in Oklahoma’s third land run after a presidential proclamation by President Benjamin Harrison.

However, the disestablishment of a formal reservation did not entirely eliminate the tribe’s authority and jurisdiction. As highlighted in the oral arguments for the Stroble v. Oklahoma Tax Commission case, reservations can be “formal” or “informal.” Informal reservations are lands held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of a tribe.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

Trust lands expand authority of western Oklahoma tribe

Over the past few years, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes have expanded their informal reservation by putting more land into “trust status,” a process which requires approval from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Recently President Joe Biden signed an executive order that includes efforts to streamline the process for placing land into trust for tribes.

Since 2020, three properties under the jurisdiction of the tribe have been given trust status. Before that, Wassana told the Tribal Tribune that “research going back over 40 years has shown that the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes have never successfully placed one single acre of land into trust status.”

In June 2020, the tribe successfully placed a half-acre plot of land including the Geary Community Center into trust status. In January 2022, a 6.8-acre plot of land south of Geary, known informally as “Rodeo Joes tract,” was also granted trust status.

In November 2023, the tribe successfully petitioned to place a 79-acre tract of land in Woodward into trust status. The land acquisition increased the territorial jurisdiction of the tribe by more than tenfold, and it could pave the way for casino gaming developments in the area.

While no plans for the 79-acres put into trust have been officially announced, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Tribune reported that Wassana indicated it would be used for economic development.

“Hopefully, we can offer tourists or travelers in that northwest quadrant a place maybe to shop, entertain, get gas, have an overnight stay and those types of things we can develop there just outside of Woodward,” Wassana said.

Wassana has also pushed for the return of lands making up Fort Reno, currently held by the federal government. The dispute over the lands in question is decades old and involves over 9,000 acres under the control of the U.S. Department of Agriculture since 1947. The fort operated as a military base between 1874 and 1947, and numerous efforts by the tribes to reclaim the land have failed, including contentious negotiations in the 1990s involving a proposed U.S. military graveyard and the subsequent placement of baboon research facilities at the USDA site, an action viewed by some as retaliatory.

Moving land into trust allows a tribe to exercise more control over the land, including granting criminal jurisdiction for crimes committed by Native Americans and granting some immunity from state taxation. Trust lands are sometimes called “informal reservations” since they possess the same legal status — Indian Country — as formal reservations.