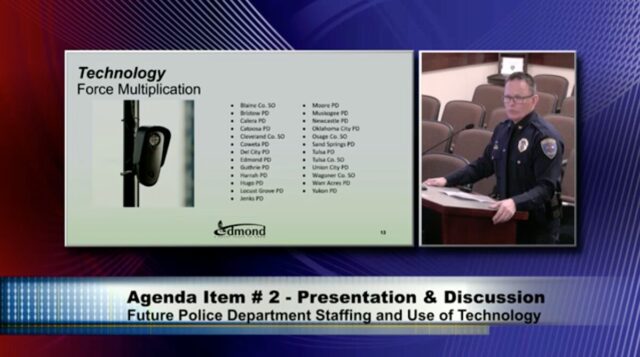

The Edmond Police Department joined about 40 law enforcement agencies across the state when it contracted with Flock Safety in March 2023 to install automatic license plate readers in public, high-traffic areas across the city to aid in criminal investigations, but their use has been widely debated among privacy advocates.

Organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union have fought the use of ALPRs, citing the Fourth Amendment and concerns with data collection on innocent motorists. Recently, the Oklahoma State Senate voted down a bill that would have allowed ALPRs to be placed on state highways, with Republicans and Democrats alike expressing concern about the measure.

“These automated license plate readers raise significant concerns, particularly whenever we are talking about 30-day holding of these (images). It really is a dragnet,” Sen. Dusty Deevers (R-Lawton) said during floor debate March 14. “It can end up forming a pre-crime committee of sorts because these ALPRs collect data without the knowledge or consent of individuals.”

However, Edmond Police Chief J.D. Younger said he believes Flock Safety’s ALPRs have worked well for the community so far. The City of Edmond paid Flock Safety, headquartered in Atlanta, $31,000 in 2023 for the implementation of 10 ALPRs and software allowing Edmond police officers to access the recordings, which Flock hosts itself.

“I think it’s been positive,” Younger said. “It’s an annual contract that expires every May. And so, in theory, there are outs. It’s not perpetual. We intend to keep it going because we think it has been beneficial.”

Meanwhile, the OKC City Council recently approved integrating Oklahoma City Public Schools camera feeds with the Oklahoma City Police Department’s real-time information center, allowing officers to access those cameras during “critical incidents.” Despite claims that Edmond Public Schools has also agreed to OKCPD’s camera integration program with the same company, district staff say otherwise.

EPD requesting renewal, expansion of Flock Safety program

Tonight, Younger is scheduled to appear before the Edmond City Council and request approval to purchase four more ALPRs, which would extend the department’s contract with Flock Safety for another year at a $46,450 cost.

According to the Edmond Police Department’s Flock transparency portal on April 5, Edmond’s ALPRs scanned more than 314,000 vehicles in the prior 30-day period and had rendered two “hotlist hits.” That means two license tags associated with crimes that were entered into the National Crime Information Center or the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children databases were captured on Flock’s ALPRs in Edmond.

That rate of hotlist hits reflects a marked decrease from the department’s 60-day trial period last year. At an Edmond City Council workshop in August, Younger said the department was alerted to 107 “hotlist hits” during that trial period.

License plate records gathered from Flock Safety’s ALPRs are deleted after 30 days, unless images are retained for investigation, according to EPD’s contract with the company. If images are determined to be evidentiary, they can be retained throughout the related adjudication process. In addition to identifying license plates, Younger said ALPRs give a general description of the vehicle, including color and even bumper stickers.

However, Younger said a hotlist hit does not constitute probable cause.

“It requires human intervention. A hit on that tag is not probable cause do to anything.” Younger said. “It is just reasonable suspicion for you to look into and see, ‘Is that related to this?'”

Owing to sensitivity surrounding surveillance, government agencies such as the Bureau of Justice Assistance encourage law enforcement agencies to engage stakeholders prior to installing such technology. For example, in 2022, the Tulsa Police Department released the location of its then-25 ALRPs provided by Flock Safety and discussed the technology with the community prior to installation.

FROM 2023

Stopped 5 times in 2 months, Saadiq Long seeks answers and protection with OKCPD lawsuit by Michael McNutt

While Younger kept council members apprised of his department’s interest and ensuing agreement with Flock Safety through Edmond City Council workshops in February 2023, August 2023 and January, other efforts to connect with community members about ALPR implementation have been limited.

“I don’t know that there was an overt effort to have community connections and things like that, but I do think there was a concerted effort to share with both the existing stakeholders that we already have partnerships with and with policymaking officials that it’s our intent to utilize this,” Younger said.

The City of Edmond denied NonDoc a request for the location of EPD’s 10 ALPR cameras, citing 51 O.S. § 24A.8(B)(1) and 51 O.S. § 24A.28(A)(3), which say the records are not specifically listed as public under the Open Records Act and say that “records including details for deterrence or prevention of or protection from an act or threat of an act of terrorism” are not subject to public inspection.

With Flock Safety’s product line, law enforcement agencies can allow other law enforcement agencies across the country to access their cameras if both utilize Flock Safety. However, the City of Edmond also denied a request asking what other agencies EPD allows to access its cameras.

Younger said there are audit logs in place to track officers’ activity while they navigate the technology. Additionally, officers are trained in the technology before use, Younger said.

“Unless it’s giving you a hit, you don’t proactively mine it,” Younger said. “There’s guidelines and rules of why you access, and so there’s audit logs. So if you get in [the system] you have to say who you are, why you’re running it.”

According to Flock Safety’s transparency portal for EPD, officers made more than 90 searches in the databases over the last 30 days.

As technology continues to evolve, Younger said there will always be a balancing act between public safety and privacy interests.

“The Fourth Amendment will always be prevalent in it because there are people with legitimate privacy concerns. I get that people are concerned about it, but I think the case law is pretty solid that public spaces — we can capture them,” Younger said. “I think there’s some some good governance in place. I think the audit tracking is solid, so if you do have a bad actor — which you’ve got a bunch of humans, I’m not saying that you can’t have a bad actor — but there’s accountability measures in place for that.”

Follow NonDoc’s Edmond coverage

Senate bill allowing ALPRs on highways fails — for now

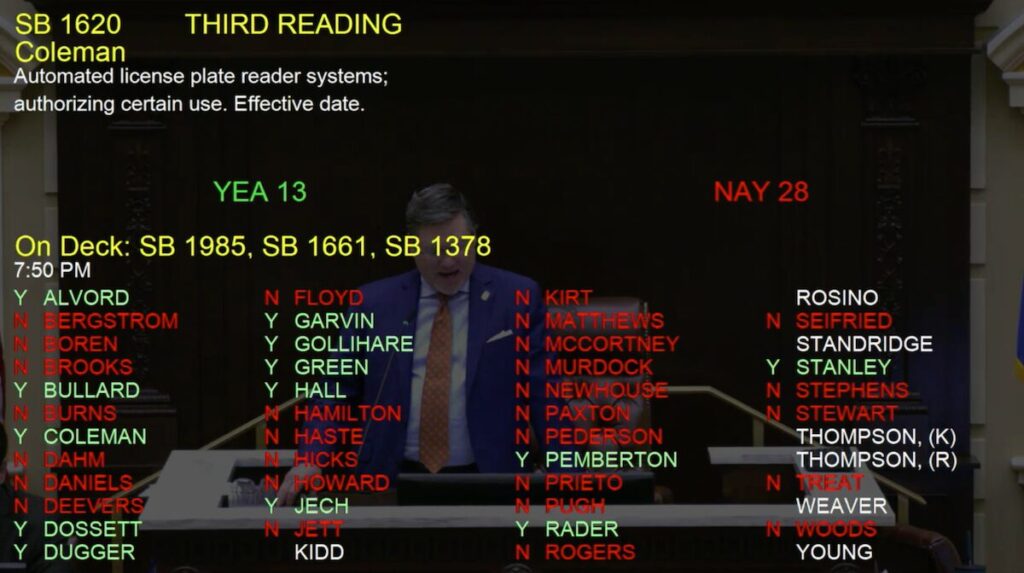

Senate Bill 1620, authored by Sen. Bill Coleman (R-Ponca City), would have allowed law enforcement agencies to place ALPRs on Oklahoma highway rights of way “to aid in criminal investigations or searches for missing or endangered persons.” However, after legislators from both parties expressed concern about data retention and privacy during a March 14 floor debate, the bill failed 13-28.

Flock Safety’s director of communications, Holly Beilin, said the company was “disappointed that the common sense guardrails proposed” in the bill did not advance.”

“ALPR technology has helped Oklahoma law enforcement solve hundreds of serious violent and property crimes and recover dozens of missing persons,” Beilin said. “Tulsa Police Chief Franklin stated the ALPR system was like ‘flipping the light switch on.’ While the Flock Safety system already has robust guardrails around responsible data management and security in place, we support regulation by our elected governing officials to ensure good practices and policy around the use of this critical public safety tool.”

In order to legally use the ALPR system, SB 1620 proposed that law enforcement agencies shall:

- establish a policy governing the use of such system to include a training process for law enforcement officers who will use the system and an auditing schedule to ensure proper use as provided for in this section, and;

- obtain a permit from the Department of Transportation before the installation of an automated license plate reader system on a state or interstate highway.

SB 1620 states that these ALPRs “shall be for official law enforcement purposes only, and shall only be used to scan, detect, and identify vehicles and license plate numbers” for identification of:

- stolen vehicles;

- vehicles involved in an active investigation;

- vehicles associated with wanted, missing or endangered persons, and;

- vehicles that register as a match the National Crime Information Center or any other relevant federal, state or local database.

Like Edmond’s ALPR system, SB 1620 would have allowed license plate data and vehicle recordings to be retained for 30 days. If the license plate record were used as part of a criminal investigation, then it “may be retained until final disposition of the matter.”

The Senate floor debate March 14 saw senators on both sides of the aisle align against SB 1620.

Sen. Carri Hicks (D-OKC) said she feared the legislation would turn state highways into a “surveillance state.”

“I truly support measures that ensure public safety,” Hicks said. “However, the bill before us is concerning for many reasons. I’m concerned about limiting or restricting movement across state lines. I’m concerned that this is turning our state right-of-ways into a surveillance state.”

Sen. Shane Jett (R-Shawnee) expressed similar concerns.

“This is an extension and a continuation of the surveillance state,” Jett said. “With the weaponization of the [Department of Justice], with social credit scores, we’re getting closer and closer to a complete and total surveillance state like you have in China.”

Sen. Nathan Dahm (R-Broken Arrow) took issue with a portion of SB 1620 that would have required law enforcement agencies using ALPRs to make public “a list of all state and federal databases with which the data was compared, unless the existence of the database is not public.”

“It’s comparing [license plate data] to databases that are not publicly known. The (Oklahoma) Fusion Center could be sharing that information, not just with other states or the United States, but with other foreign countries as well. It can open that up through that data sharing,” Dahm said. “The government should not be tracking you and keeping your data for 30 days, tracking your movements on the odd chance that you might be committing a crime.”

To close debate, Coleman said numerous law enforcement agencies across the state are already using automatic license plate readers, and he repeated that the bill would “save lives.”

“It will definitely save lives. It has to be an ongoing criminal investigation for the license plate information to be sent to law enforcement. Law enforcement is not tracking anyone. They are looking for bad people doing bad things,” Coleman said. “Law enforcement all over the state of Oklahoma is already using this technology. This will not make the technology go away. It will put the technology on state right-of-ways to help save lives.”

To Coleman’s point, dozens of law enforcement agencies in Oklahoma are using Flock Safety’s cameras and data sharing capabilities, including via agreements with agencies in Texas and Kansas.

However, Flock Safety’s transparency portals for the Edmond Police Department and the Tulsa Police Department do not disclose to which agencies their records are being shared. Perhaps owing to its larger footprint and the presence of Interstate 44, TPD’s Flock Safety system registered 700 times as many “hotlist” hits over the past month compared to Edmond. With 105 cameras, TPD registered more than 1,500 hits, and officers made more than 1,900 searches.

Like Edmond, Del City has 10 cameras and registered 40 hits over the past month, with officers making 105 searches. And unlike Edmond or Tulsa, the Del City transparency page outlines the dozens of “external organizations with access” to their camera hits, including the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, the Texas Financial Crimes Intelligence Center and numerous police departments and sheriff offices in Oklahoma.

OKC claims EPS has camera integration, district says otherwise

Flock Safety camera contracts are not the only systems drawing local questions recently.

The Oklahoma City Council voted 5-3 on March 26 to allow Oklahoma City police officers to access school camera feeds during “critical incidents.” The memorandum, prepared for council members by Craig Freeman, OKC city manager, states that Edmond Public Schools — among other districts — has also agreed to integrate OKCPD’s Fusus information center with its camera systems. However, EPS staff have said otherwise.

“No, we do not have a contract with Fusus,” said Jeff Bardach, EPS’ public information officer. Bardach said district staff are gathering information from OKC about how the software functions, but EPS leaders have expressed confusion over why Freeman’s memo stated what it did.

Fusus, a company headquartered in Peachtree Corners, Georgia, offers a “real-time information center,” sometimes referred as a “real-time crime center,” that consolidates surveillance data from traffic cameras, drones and other technology into a single platform. On March 26, the OKC City Council amended its $200,000 January 2023 contract with the company — adding a $90,000 increase — to allow OKCPS to integrate its camera systems with the real-time information center.

Dissenting council members expressed concerns about the privacy of OKCPS students.

“As this relates to filming minors without their parents’ consent — we reference 1984 and Big Brother — we’re doing it,” said JoBeth Hamon, OKC’s Ward 6 councilwoman who voted against the measure. “And we’ve really not told the public adequately what they can expect and how we’re avoiding and ensuring that this technology and this intrusion into people’s lives is not being abused.”

Wade Gourley, OKCPD’s chief, said law enforcement already had access to OKCPS cameras “during the event of an emergency,” but that the process is delayed. Initially, Gourley told Hamon there were “strict guidelines” as to when law enforcement can access those camera feeds, but later he said they “can’t be so specific to try and narrow down every particular incident.”

“It’s going to be pretty much any time that a 9-1-1 response is required in the school and something active is going on there, those teachers or someone in that school needs help (…) if the incident requires it that we be able to get eyes on that to be able to advise our officers where they need to respond in the school,” Gourley said.

During her remarks, Hamon cited the Bureau of Justice Affairs’ white paper on the implementation of real-time information centers, which states in part:

Engaging stakeholders before you start recording their activities, capturing their license plates, or monitoring their citizens, is an important step that will further sustain the agency’s legitimacy and trust, which ultimately will help ensure a safer community.

“This is not me (saying this),” Hamon said. “They’re giving the blueprint for, ‘Do you want the public to trust your police force and your police agency? Here’s how you do it.’ As far as I have seen, we have not done that in any meaningful way.”

Hamon said council members should have given the agreement more scrutiny prior to voting.

“We’re just sort of approving these things without any community involvement or awareness,” Hamon said. “Those are minors in schools. They are required to be there by law. They don’t have an option to not go into that building without legal consequences, and they don’t have an option to not be recorded.”