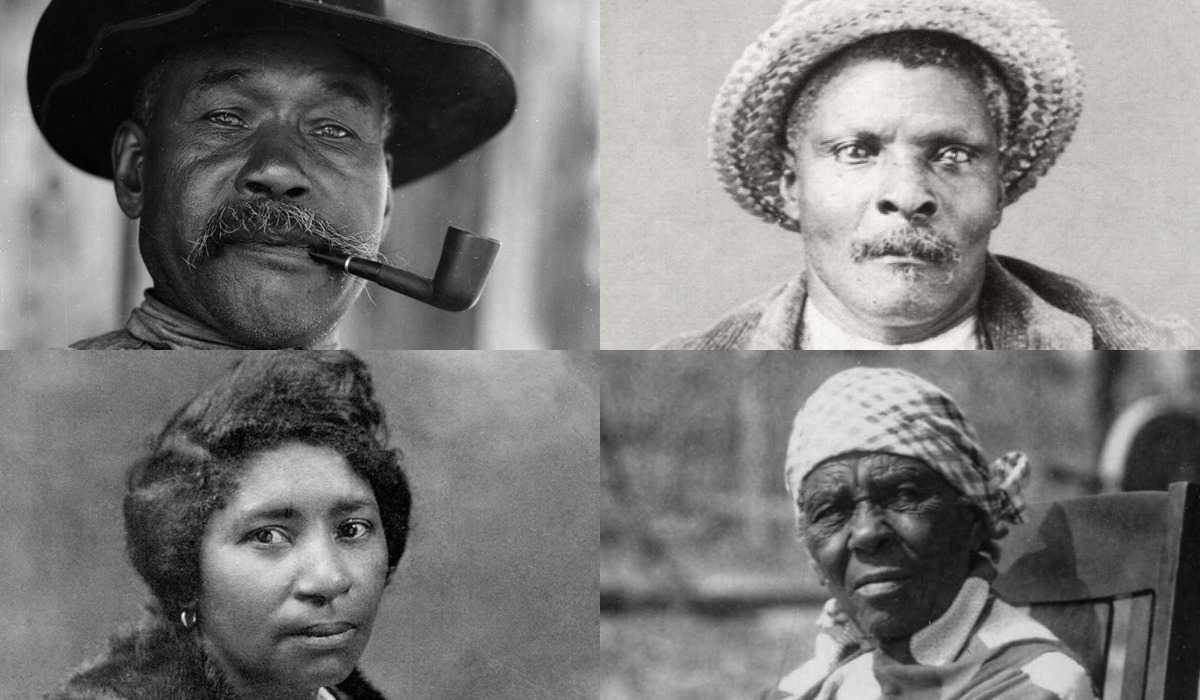

The Cherokee Nation announced efforts in February to push for a change in how federal law determines Indian status under the Major Crimes Act that would require Cherokee Freedmen to be recognized as Native Americans by federal courts. While any congressional request over Indian Country is slow going, the policy proposal affords a closer examination of how courts determine who is an Indian.

Currently, federal law uses a test from an 1846 murder case that requires both tribal connections and “Indian blood” for a person to be deemed Native American for the purposes of criminal jurisdiction. Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. is hoping Congress will narrow that test and require only tribal citizenship.

“Your tribal citizenship is, in fact, ignored because there is a two-part test that the courts have used to interpret the Major Crimes Act that says you have to be a citizen or a member of the relevant nation, and you have to have a blood quantum,” Hoskin said in late February.

Marilyn Vann, a Cherokee Freedman and the Cherokee Nation’s environmental protection commissioner, said several Cherokee Freedmen have been charged in state courts under the current interpretation of the Major Crimes Act since the McGirt v. Oklahoma decision.

“I know in the majority of those cases the people, if they really could not afford to take it up higher, they just did some kind of a deal with the state,” Vann said in referencing plea agreements. “Here we are: separate but not equal.”

Congress or courts? Routes for Cherokee Freedmen reform

Also in February, Hoskin signed an executive order to improve outreach to Cherokee Freedmen, the descendants of the tribe’s former slaves.

The order sought to “address any deficiencies” with existing programs, and its provisions included:

- Acknowledgement that “the injuries inflicted not only by our enslavement of their ancestors, but more than a century of our denial of their civil rights and our under investment in communities they call home, have not been fully healed;”

- A task force charged with examining and producing a final report about Cherokee Freedmen participation rates in Cherokee Nation programs and services; and

- Updated annual plans of action within executive agencies “for community and public outreach to historically excluded groups within Cherokee society.”

Hoskin’s executive order stands in contrast to policies of the Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole nations regarding Freedmen. Nonetheless, Hoskin indicated that the Cherokee Nation was still considering a variety of strategies — including lobbying Congress and pursuing litigation — to change federal law and grant Cherokee Freedmen recognition in federal court.

“This effort (…) is to get Congress to make a really narrow change in the law or to find the appropriate case to go up through the courts and maybe advocate for a court to say, ‘Blood quantum is not really a test or a prong that is relevant and we shouldn’t apply it,'” Hoskin said.

He emphasized that conversations are “still in the education phase” with Congress.

“I talked to the leaders of the other Five Tribes before we made the push, and they all expressed support because of the way we frame it,” Hoskin said. “It is, as you asked, an expression of sovereignty. If a tribe determines that this person is a citizen, that’s where it begins and ends in terms of the analysis.”

RELATED

The long fight for Freedmen citizenship continues in Oklahoma tribal nations by Joe Tomlinson

In a broader context, however, the Cherokee Nation’s push for federal change could stoke congressional tensions about how Oklahoma’s other largest tribes in which some families owned slaves currently decline to offer citizenship to their Freedmen descendants. While Hoskin said the Cherokee Nation’s advocated change to the law would not affect the Freedmen of the other Five Tribes, the Congressional Black Caucus and Freedmen advocacy groups have pressured those tribes to acquiesce in recent years.

A case pending before the Muscogee Nation Supreme Court alleges that the tribe has violated its Treaty of 1866 by prohibiting citizenship to descendants of Muscogee Freedmen. The Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole nations have also drawn criticism for not granting citizenship to Freedmen, with the Seminole Nation being federally mandated in 2021 to offer its Freedmen COVID-19 vaccinations and other health services despite denial of citizenship.

Asked about the situation, Muscogee Nation press secretary Jason Salsman indicated the Muscogee Nation had no comment on the Cherokee Nation’s Freedmen efforts. Choctaw Nation public relations manager Randy Sachs had a similar response.

“Routinely, we don’t comment on other tribes’ proposals, resolutions and such,” he said.

Asked about the Cherokee Nation’s proposal, Muscogee Freedmen advocate Eli Grayson emphasized that, under the Major Crimes Act, tribes prosecuted numerous cases involving Freedmen before statehood. He also argued that the U.S. Supreme Court case Morton v. Mancari — which found a Bureau of Indian Affairs hiring preference for members of federally recognized tribes was based on a “political, rather than racial” category — is the correct definition of Indian to use in a criminal context.

“In 1885, they were prosecuting Freedmen in the Cherokee Nation, in the Creek Nation and in the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole nations,” Grayson said. “This modern day exclusion is just about how we want to define Indian today and (…) in Morton v. Mancari (the court held) an Indian is anybody who is a citizen of their tribe.”

Attorney Brett Chapman, who specializes in Federal Indian law cases, praised the move of the Cherokee Nation.

“It is the right thing to do, and I commend the Cherokee Nation leadership for taking a principled stand for equality,” Chapman said.

How courts determine who is an Indian

The Founding Fathers had something in mind when they wrote the word “Indians” into the U.S. Constitution, but they left any definition out of their final draft. Congress’ legislation has followed this pattern, frequently invoking the term Indian, but not always defining its meaning or application.

Sometimes Congress does define the word Indian, but only for a specific statute’s application. As a result, courts sometimes define “Indian” in the context of who is eligible to benefit from specific programs or in the context of arts and crafts. But overall, American courts lack a uniform definition of Indian.

RELATED

‘It’s clearly unresolved:’ Lankford requests solution in hearing on Five Tribes’ Freedmen by Andrea Hancock

The Major Crimes Act is the federal law that requires Indian defendants be tried in either tribal or federal court for crimes committed in Indian Country, a legal term of art recently applied to the eastern half of Oklahoma following the U.S. Supreme Court’s McGirt decision. According to the act, “any Indian who commits against the person or property of another Indian or other person any of the following offenses (…) shall be subject to the same law and penalties as all other persons committing any of the above offenses, within the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States.”

In the context of criminal law, Congress has never defined the word Indian, instead leaving that job to federal courts. Facing a slew of criminal laws about Indians without a binding definition, the judiciary has charted the federal government’s course in how courts determine who is an Indian, at least for criminal jurisdiction.

Like anything developed by the judiciary over nearly two centuries, the definition of Indian has shifted over time, with 19th and 20th century courts sometimes reaching wildly different conclusions. Weston Meyring’s 2006 article, I’m an Indian Outlaw, Half Cherokee and Choctaw, examines several decisions from those centuries.

By the 21st century, most courts have settled on a two-part inquiry for determining Indian status.

First, courts apply the United States v. Rogers test from 1846, which looks for “Indian blood” and connections to a tribal government.

When applying the “Indian blood” part of the Rogers test, courts usually look for blood quantum in a federally recognized tribe. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States federal government would send Indian agents to create “tribal rolls,” essentially censuses of the citizens of tribal governments.

People listed on the rolls were assigned a blood quantum, or a fraction that represents the amount of “Indian blood” each person was believed to possess by Indian agents. The United States Bureau of Indian Affairs continues to track the blood quantum of the descendants of tribal enrollees to this day, and it issues descendants “certificate of degree of Indian blood” (CDIB) cards. The concept of blood quantum remains controversial.

Second, when looking for tribal connections or recognition, courts typically undertake the four-factor St. Cloud analysis, which examines:

- “Enrollment in a tribe;”

- “Government recognition formally or informally through providing the person assistance reserved only to Indians;”

- Whether someone is “enjoying benefits of tribal affiliation;” and

- “Social recognition as an Indian through living on a reservation and participation in Indian social life.”

While Cherokee Freedmen can clearly meet the St. Cloud factors, many fail the first part of the Rogers test: Indian blood. When the Dawes rolls were created, former Cherokee slaves were listed on the rolls as Freedmen, and agents for the rolls usually made no efforts to record “Indian blood” for Freedmen, even if they had Cherokee ancestors.

In 1896, Justice Henry Billings Brown — citing the Rogers case — wrote the opinion for Alberty v. United States and found that a Cherokee Freedman made a citizen by the Cherokee Nation’s 1866 treaty with the United States “must be treated as a member of the Cherokee Nation, but not an Indian,” for the purposes of criminal jurisdiction.

“While [Article Nine] of the treaty gave him the rights of a native Cherokee, it did not, standing alone, make him an Indian within the meaning of Rev.Stat. § 2146 or absolve him from responsibility to the criminal laws of the United States, as was held in United States v. Rodgers (sic) and Westmoreland v. United States,” Brown wrote.

Brown’s mention of “responsibility to the criminal laws of the United States” was odd for its time considering Freedmen were not given U.S. citizenship until the 20th century alongside other members of the Five Tribes. A companion case to Alberty held courts should not presume Black people are not Indians, leaving courts with the direction that Freedmen are neither presumed to be Indian nor presumed to be non-Indian.

Today, courts are left following these century-old cases and cannot presume Freedmen are Indian or non-Indian. Instead, they must apply the Rogers test individually to each defendant and make a determination on whether they possess “Indian blood” when determining criminal jurisdiction.

According to the Cherokee Phoenix, there are about 15,000 Cherokee Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Cherokee Nation today. Vann described the Rogers decision and its progeny’s application to Freedmen as “incorrect interpretations.”

“The situation of the intermarried whites (like Rogers in the 1840s) is not the same as the situation of the Freedmen,” Vann said. “The rights of the intermarried whites were less than the Freedmen or the adopted Delaware or adopted Shawnee.”

The 1840s murder that defined ‘Indian’

In 1846, a white man with Cherokee citizenship named William S. Rogers stabbed his brother-in-law to death with a $5 knife. While other details of the slaying appear lost to time, Rogers’ case still defines how courts determine who is an Indian for criminal jurisdiction.

According to an article by professor Bethany R. Berger, Rogers and his brother-in-law, Jacob Nicholson, were both American citizens who had married Cherokee women. Under Cherokee law of the time, they were also considered Cherokee citizens.

Berger notes that, despite the existence of federal court records, neither woman’s name appears to have been recorded, a historical symptom of the missing and murdered Indigenous women crisis still being reckoned with today.

Rogers was a Tennessee soldier who fought against the Cherokee Nation before marrying his wife and joining her on the Trail of Tears to Indian Territory. His wife died in 1843, and on Sept. 1, 1844, he murdered Nicholson “with a certain knife, of the value of 5 dollars” and spent the next several months evading the authorities before his capture on April 2, 1845, by Cherokee Nation Sheriff Alexander Foreman.

Since the Cherokee Nation has not historically operated its own jails, Rogers was handed over to U.S. troops at Fort Gibson while he awaited trial in the Cherokee Nation. However, federal officials in Indian Territory had a different plan for Rogers. On April 5, he was sent to Little Rock, Arkansas, for prosecution in federal court.

Rogers, representing himself April 18, argued that the federal court lacked jurisdiction over him, an Indian defendant who had murdered an Indian within Indian Country.

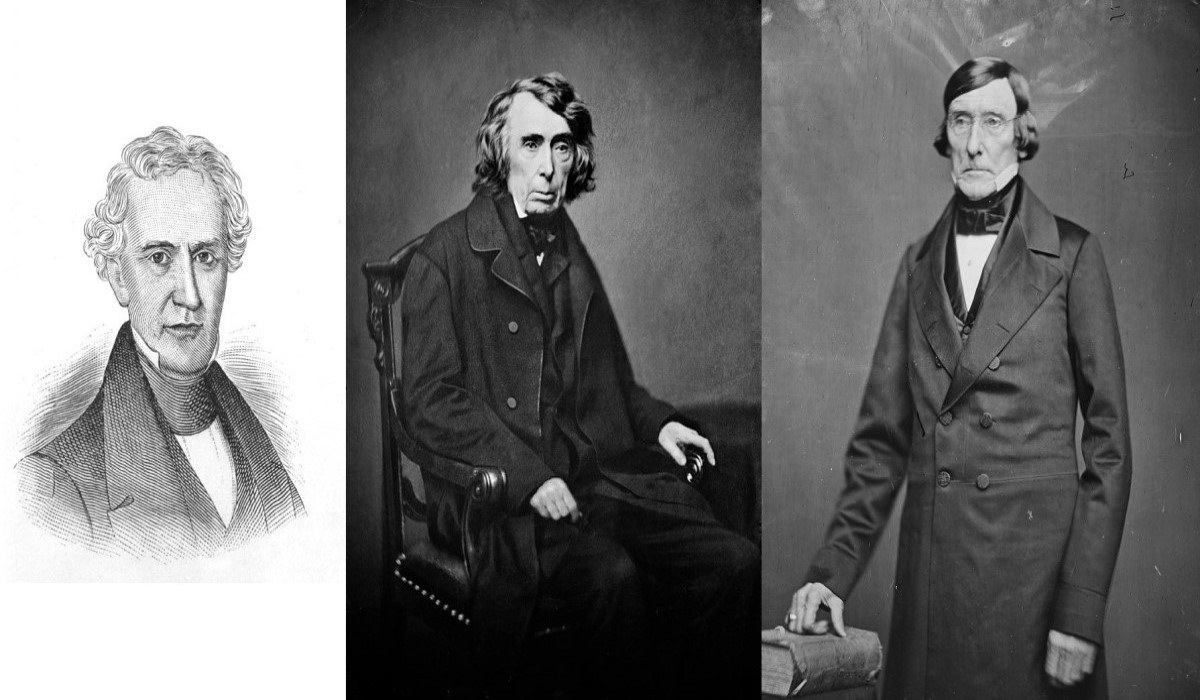

While Judge Benjamin Johnson agreed with Rogers, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Peter Daniel happened to be in town “riding the circuit,” a now-abandoned practice of Supreme Court justices traveling the nation to hear lower court cases.

Unfortunately for Rogers, the Judiciary Act of 1793 required an automatic appeal when a Supreme Court justice was in town riding the circuit, and Daniel disagreed with the district judge’s ruling. Not wanting to wait for his appeal, Rogers escaped the Little Rock jail on May 12, 1845, and drowned while attempting to cross the Arkansas River into the Cherokee Nation.

However, death did not stop the wheels of justice on Rogers’ appeal. The court clerk certified Rogers’ case record for appeal on July 28 and sent the record to the U.S. Supreme Court. During the appeal, no one informed the court of Rogers’ death, and no one appeared for the defense.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

Rogers decision denies Freedmen recognition in federal courts

Had the Supreme Court been informed of Rogers’ death, it would have likely dismissed the case. Unburdened with knowledge of the case’s mootness, Justice Roger Taney proceeded with U.S. v. Rogers and provided the outline of the legal definition of Indian that federal courts still use today.

The Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834 exempted “crimes committed by one Indian against the person or property of another Indian” from federal jurisdiction, leaving them for tribal governments to address. Rogers argued that, since both parties were legally Cherokee citizens, the Trade and Intercourse Act prevented the federal government from exercising jurisdiction.

The court disagreed. Taney, writing for the court and using a 19th-century logic of race, linked being Indian to blood and concluded the defendant Rogers “was still a white man, of the white race, and therefore not within the exception in the act of Congress.”

For Taney, the status of being Indian was not political, as it is understood today, but racial:

And we think it clear that a white man who at a mature age is adopted in an Indian tribe does not thereby become an Indian and was not intended to be embraced in the exception above mentioned. He may by such adoption become entitled to certain privileges in the tribe, and make himself amenable to their laws and usages. Yet he is not an Indian, and the exception is confined to those who by the usages and customs of the Indians are regarded as belonging to their race. It does not speak of members of a tribe, but of the race generally.

A tension exists between Taney’s century-old guideline for how courts determine who is an Indian in criminal cases and later Supreme Court cases that describe Indian status as a political relationship for the purpose of civil cases.

The Cherokee Nation’s push for a change to Taney’s old rule poses potential resolution of that tension.

(Update: This article was updated at 10:03 a.m. to adjust reference to historical events.)