Attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons is challenging the constitutionality of an emergency bill passed by the Muscogee Nation and has accused the nation’s executive and legislative branches of “sham appointments” and “court packing” ahead of oral arguments for a Supreme Court case that will determine whether Muscogee Freedmen, the descendants of slaves owned by Muscogee people prior to 1866, are entitled to citizenship within the tribe.

“The Muscogee Creek Nation — particularly the leadership of the nation being the principal chief and National Council — understand they have no basis at all to continue to oppress and discriminate against Creeks of African descent,” Solomon-Simmons said Tuesday at a press conference in Tulsa. “They believe that they have no ability to win underneath the law, so they conspired together to concoct a plan to unlawfully, illegally, unconstitutionally appoint two quote-unquote special justices.”

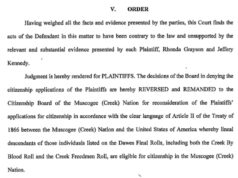

In September 2023, Muscogee Nation District Court Judge Denette Mouser ruled that the Treaty of 1866 requires the tribe’s Citizenship Board to admit Muscogee Freedmen as citizens, something tribal leaders have opposed.

“The court finds that the actions of the board in denying plaintiffs’ citizenship applications and appeals were contrary to law, specifically the Treaty of 1866 and its required inclusion of the Creek Freedmen and their lineal descendants within the citizenship of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation,” Mouser wrote in her order.

On Friday, July 26, the Muscogee Nation Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments for the appeal of Mouser’s decision filed by plaintiffs Rhonda K. Grayson and Jeffery D. Kennedy.

Since 1979, the Muscogee Nation Constitution has limited citizenship to descendants of people listed on the “Creek by blood” roll and has excluded descendants of people listed on the Freedmen roll. Both rolls were created simultaneously by the United States in the early 20th century to be definitive lists of tribal members, actions that have drawn their own historic criticism.

Now, Solomon-Simmons’ accusations follow an emergency bill proposed by Principal Chief David Hill and passed by the Muscogee National Council in June that allowed Hill to appoint a “special justice” to the court when a judge recuses. Special justice nominees must also be approved by a majority of the National Council and can only serve on the court to hear one case.

In the same emergency meeting where the amendment was passed, the Muscogee National Council also approved the appointment of Special Judges James Jennings and Samuel Deere to hear the Freedmen appeal. Justices Leah Harjo-Ware and Amos McNac both have recused from the case.

“It is such an unbelievable development that, in my 20 years of practice, I’ve never heard of anything like this,” Solomon-Simmons said.

Muscogee Nation press secretary Jason Salsman referred to Solomon-Simmons’ allegations as “lies” and said the plaintiffs in the cases are “not Creek at all.”

“The brazenness with which this group lies is appalling. Individuals of African descent who are also Creek are more than welcome as citizens. Indeed, many already are citizens,” Salsman said. “The issue here is that the individuals seeking citizenship are not Creek at all, and our constitution does not allow citizenship for anyone who is not a Creek descendant by blood.”

Salsman also criticized Solomon-Simmons personally for attempting to “manufacture a controversy” over the appointments.

“Damario can be relied upon for a good show but seldom the truth. [Tuesday’s] press conference, with its theatrics and hyperbole, distorted the facts to attempt to manufacture a controversy,” Salsman said. “This is a disservice to the public and deeply disrespectful to Muscogee (Creek) citizens.”

Jennings, Deere appointed to hear Freedmen case

After Harjo-Ware and McNac recused themselves from hearing Citizenship Board of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation v. Grayson, Deere and Jennings are set to replace the recused judges solely for the Muscogee Freedmen case. Their tenure expires at the “conclusion of the case.”

Jennings is a former Muscogee National Council member whose elected service spanned from 2005 to 2011 and from 2013 to 2021. He lost reelection to Nelson Harjo Sr. in 2021 and ran for reelection in 2023, finishing third in a race ultimately won by Robyn Whitecloud. During his 2023 campaign, Jennings expressed support for the Muscogee Nation Constitution‘s “Creek by blood” requirement.

Mvskoke Media’s Lawyer’d Up podcast with Jerrad Moore first reported on Jennings’ appointment and prior comments about Freedmen, raising questions about his impartiality in the case for which he has been appointed as a special justice.

“My opinion on the Creek Freedmen case is that, if elected, I will support and defend the Muscogee Creek Nation Constitution, which states that it is by blood,” Jennings said when asked about his stance in 2023.

Salsman said the statements by Jennings are “no bombshell.”

“It’s nothing more than a candidate committing to do what every other government official in America is obligated to do — uphold the constitution they swore an oath to uphold,” Salsman said. “The notion that any official of any government should pick and choose when to follow the law is dangerous and nonsensical. As a U.S. military veteran and longtime MCN Council representative, this is something Mr. Jennings would understand well.”

Deere ran for the Muscogee Nation Council in 2021 against incumbent Travis Scott and placed third in the primary election. Scott later lost the runoff election to Sandra Golden. Deere is fluent in the Muscogee language and previously worked as the director of social services for the Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town.

Neither Jennings nor Deere is an attorney by trade, and neither is licensed to practice law.

Tribal governments set their own requirements for political office and sometimes choose to allow non-attorneys to serve as tribal judges. Tribal judges appointed without a law degree are usually selected for their knowledge of the tribe’s traditions.

The Muscogee Nation Constitution’s sole requirement for Supreme Court Justices is that they lack a felony conviction. Of the seven justices currently set to hear the Freedmen case, only four graduated from law school.

Asked about neither special justice being an attorney, Salsman said there was no requirement in either the U.S. Constitution or the Muscogee Nation Constitution that supreme court justices be licensed attorneys. The last U.S. Supreme Court justice appointed without graduating from a law school was James F. Byrnes in 1941. (Similarly, Oklahoma does not require its attorney general to be a lawyer.)

Salsman also said that neither Justice Amos McNac, who recused, nor Justice George Thompson is an attorney by trade.

Still, Jennings’ comments on the subject of the litigation prior to his appointment could lead to his recusal from the case. Solomon-Simmons said he planned to file a motion asking Jennings to recuse because of his prior statements.

The Muscogee Nation’s Code of Judicial Conduct bars judges from making “pledges or promises of conduct in office that could inhibit or compromise the faithful, impartial and diligent performance of the duties of the office.” Prior to a 2012 amendment to the code, a judge was required to recuse whenever they previously served as a government official and specifically commented on the merits of a case.

‘Small town corruption applied to a newly expanded post-McGirt legal jurisdiction’

Solomon-Simmons’ petition (embedded below) argues that the emergency bill is an unconstitutional violation of the separation of powers in the Muscogee Nation Constitution.

“The threat to the court’s internal deliberation process — and its very independence as a branch of government — is much greater, and any attempt to control the Supreme Court under the guise of legislation cannot be tolerated,” Solomon-Simmons wrote. “The National Council and Chief Hill cannot hand-pick lackeys to replace recused justices of this court.”

In the petition, plaintiffs argue that the new law allows special justices to be appointed to affect the outcome of specific cases. Since special justices only sit for the term of one case, the executive and legislative branches could choose special judges based on how they will rule on a specific case in front of the court, thus limiting the independence of the tribe’s judicial branch.

“It is small-town corruption applied to a newly expanded post-McGirt legal jurisdiction with the power to jail human beings and/or strip them of their property,” Solomon-Simmons said. “This court must take the opportunity to protect its citizens — and everyone now subject to the laws, courts and jurisdiction of the MCN post-McGirt — from the political branches’ unconstitutional arrogation of judicial power.”

Salsman called the “attacks” on the appointment of special justices “a distraction.”

“Every issue that comes before the court deserves the consideration of a full panel of justices, and the appointment of special judges follows the same process as every other judge,” Salsman said. “Judges are nominated by the executive branch and confirmed by the legislative branch.”

While the majority of the plaintiffs’ petition focuses on concerns about the separation of powers, it also argues that the Muscogee Nation chief and National Council did not follow the new law’s procedure for appointing the special justices.

The process for appointing special justices requires the clerk of the Muscogee Nation Supreme Court to notify the tribe’s chief of recusals in writing before he proposes a special appointment to the council. The brief alleges that, since the new law was passed in the same session as the appointments, it was impossible for the clerk to have notified the chief in writing of the recusals before he made the appointments.

Asked whether Hill had received notice in writing of the recusals before making the appointments, Salsman said that, when the recusals were filed, “every attorney in the case gets a copy” and the nation’s attorneys advised the chief on litigation developments as they occurred.

“All pretty routine,” Salsman said.

Read the full petition here