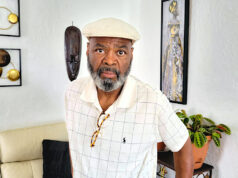

Gov. Mary Fallin finally received her first chance to appoint a justice to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, but her pick has raised eyebrows, caused controversy and earned lawsuit threats.

Of primary concern are a few lines within that pesky document called the Oklahoma Constitution. You know, it’s the one the Oklahoma Supreme Court is tasked with upholding and interpreting.

You might say some people value its specificity, though it’s always open to interpretation via precedence and political power.

Home is where … you are a ‘qualified elector’?

Under a layperson’s reading of Article 7, Section 2 of the Oklahoma Constitution, 35-year-old Patrick Wyrick would appear ineligible to fill the Oklahoma Supreme Court post to which Fallin has appointed him.

Wyrick was selected from multiple Judicial Nominating Commission suggestions to fill the robe of retired justice Steven Taylor, who hailed from the state’s second supreme court district. (The court’s justices are chosen from nine separate districts in an attempt to ensure balanced geographical representation on the bench.)

To that end, the Oklahoma Constitution specifies:

Each Justice, at the time of his election or appointment, shall have attained the age of thirty years, shall have been a qualified elector in the district for at least one year immediately prior to the date of filing or appointment, and shall have been a licensed practicing attorney or judge of a court of record, or both, in Oklahoma for five years preceding his election or appointment and shall continue to be a duly licensed attorney while in office to be eligible to hold the office.

Unfortunately, Wyrick’s status as a “qualified elector” for at least one year in southeastern Oklahoma’s second district sits in doubt.

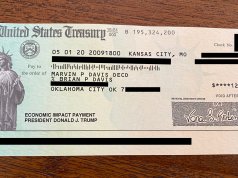

OKC Fox’s Phil Cross reported Wednesday that Wyrick, who has served as solicitor general under Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, registered to vote in Atoka County on Oct. 12, 2016. Election Board data used to populate the local site www.BadVoter.org show the same thing.

Cross also reported that Oklahoma Election Board information shows Wyrick having voted in Cleveland County since at least 2000.

Wyrick’s judicial application includes contradiction

Wyrick’s “application for Oklahoma judicial vacancy” was submitted Oct. 27, just more than two weeks after he changed his voter registration. As part of the application, the former GableGotwals associate had to answer a question about his “length of residency in the district.”

On the PDF embedded below, Wyrick said he has lived in the district, “Since birth,” and he listed his “residence address” as Atoka.

Six questions later, however, Wyrick was asked to list his “places of residence” over the past 10 years. He listed previous addresses in Norman, Broken Arrow and Moore, while noting that he has lived in Oklahoma City from “2016-now”.

That answer conflicts directly with Wyrick’s answers to question seven.

The application concludes with Wyrick signing in affirmation of the following statement: “I have read the questions in the foregoing application and questionnaire and have answered them truthfully, fully and completely.”

Beyond the application’s own contradictions, multiple public documents show Wyrick has resided outside of district two for more than a decade.

A search of the Cleveland County assessor’s website shows that Wyrick and his wife own a house near Moore-Norman Technology Center. They purchased the house in November 2015, according to records.

And while a 2002 Garfield County speeding ticket noted Atoka as a residence for Wyrick, the OSCN documentation listed Norman as his “current” residence circa 2004.

Wyrick also married his wife in 2004 in Oklahoma County.

Precedent protection?

While the Fallin administration does not appear to have pushed back publicly on Cross’ story, a source with knowledge of the situation said precedent with other justices’ residencies could support Wyrick’s appointment, if challenged.

The individual also pointed to an Attorney General’s opinion regarding the definition of “qualified elector.” Article 3, Section 1 of the Oklahoma Constitution states:

Subject to such exceptions as the Legislature may prescribe, all citizens of the United States, over the age of eighteen (18) years, who are bona fide residents of this state, are qualified electors of this state.

By interpreting that language to mean an individual must simply meet the general eligibility requirements for voting in Oklahoma rather than actually voting in a specific jurisdiction, Wyrick could qualify as the appointee.

But, lawyers being lawyers, some might argue that Wyrick has not been “in the district” as prescribed in the court-eligibility requirements.

One case to verdict

The nomination, appointment and potential legal challenge of Patrick Wyrick as an Oklahoma Supreme Court justice could become yet another bumbling faux pas for a Fallin administration largely defined in public perception — fairly or not — as incompetent and/or duplicitous.

NonDoc has received several complaints about Wyrick’s qualifications for the Supreme Court post. Aside from his residency, onlookers have questioned his limited courtroom experience.

On the application embedded above, Wyrick said he has taken only one civil case to verdict on a bench trial.

He said he has taken no criminal or civil cases to verdict in front of a jury.

A bad look for the governor

That the governor would select an attorney who has never been a judge and who holds limited trial experience was bound to rub some of Oklahoma’s legal community the wrong way, but the major questions about Wyrick’s basic eligibility to serve his post have become yet another symbolic headline that undercuts the public’s confidence in its government.

Oklahoma has seen a slew of such headlines over the past six years, everything from disposal-well drama to revenue failures to teacher shortages and botched executions.

On that last topic, Wyrick actually represented the State of Oklahoma in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015. His argument to the court proved effective in yielding a 5-4 affirmation of lower-court opinions that Oklahoma’s use of midazolam as a pre-execution anesthetic does not violate the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

In his argument, however, Wyrick was sternly challenged by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who said Wyrick had misrepresented multiple statements in his brief, including the FDA’s labeling of midazolam.

Sotomayor said Wyrick’s brief made claims of fact that were “directly contradicted” by the citations he offered.

“So nothing you say or read am I going to believe, frankly, until I see it with my own eyes,” Sotomayor told Wyrick.

KFOR described that interaction as Wyrick “facing critics” in a recent online story, but the station hardly explained how the attorney’s argument before the SCOTUS unfolded. (The transcript of that case’s oral arguments is actually quite fascinating, and it offers a substantial look at Wyrick’s rhetorical abilities.)

Unlike Cross’ report, KFOR’s story on Wyrick did not mention concern over his residency.

‘The rule of law’

While it’s less sexy than the implication that he tried to mislead the U.S. Supreme Court, Wyrick’s potential ineligibility to serve on the Oklahoma Supreme Court (from district two) should raise red flags.

Why? Because the apparent violation of constitutional requirements would seem far more cut and dry, despite what lawyers defending Wyrick’s appointment might argue. Remember, justices often must interpret constitutional intent when determining how specifically to apply legal prescriptions.

Ironically, Pruitt offered the following quote about Wyrick’s appointment last week: “Serving as Oklahoma’s first Solicitor General, he has played an integral role in the state’s effort to defend the rule of law.”

The rule of law, eh?

Whether any litigious Oklahomans file suit to see whether Wyrick’s appointment violates Article 7, Section 2 of the state constitution should be interesting to watch.