Two of the most powerful figures in Oklahoma have formally requested that Gov. Mary Fallin stay the controversial planned execution of prisoner Richard Glossip.

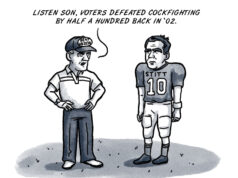

Former U.S. Sen. Tom Coburn, former OU football coach Barry Switzer, two attorneys and the co-director of the Innocence Project authored the letter sent to the Oklahoma governor. Friday, it surfaced on Huffington Post, though the version posted did not contain a date.

Glossip is jailed in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester for the murder of motel owner Barry Van Treese in 1997, and he is facing a Wednesday execution by lethal injection. Van Treese was beaten to death with a baseball bat by a motel maintenance worker named Justin Sneed, who is serving life in prison for the killing.

While Glossip did not hit Van Treese himself, prosecutors relied on testimony from Sneed to convict Glossip of first-degree murder in 1998 for agreeing to pay Sneed for killing Van Treese. That conviction was overturned on appeal, but Glossip was subsequently convicted again of the crime in 2004 and sentenced to death. He has appealed, unsuccessfully, all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and his defenders argue the 2004 conviction was too reliant upon the testimony of Sneed, who avoided the death penalty himself by pointing the finger at Glossip.

I don’t know whether Richard Glossip was involved in this murder. That may be the understatement of the year, but the fact is that 99.9 percent of the population does not know. Even Van Treese’s closure-seeking family members do not know, though they were likely as convinced as two juries were that Glossip is guilty.

We would all like to think that the U.S. criminal justice system works in these toughest and most awful of circumstances. Glossip has had his days in court, Gov. Fallin has noted, and he exercised his constitutional right to confront and challenge his accuser’s testimony. Each time, however, juries found him guilty anyway.

But what I do know is that juries have been wrong before — many times — and a growing number of criminal-justice system and anti-death-penalty advocates have been rushing to Glossip’s corner in a last-minute attempt to avoid killing a potentially innocent man. The relative of another murder victim in Oklahoma even wrote into NewsOK to tell the story of DNA evidence overturning the convictions of two men in her family member’s case. One of those men had been sentenced to death.

A study released earlier this year estimates that about 4 percent of people on death row may not be guilty of the crimes for which they were convicted. Those numbers are chilling.

While a basketball player successfully making 96 out of 100 free throw attempts in practice is phenomenal, such a rate of accuracy in state-sanctioned death sentences is far less cause for celebration. In fact, it’s a good reason to look around and wonder whether we are doing the right thing as a society.

In Connecticut, the state Supreme Court did just that over a two-year review period before determining that, in their opinion, we are not.

In August, the court announced Connecticut’s death penalty “no longer comports with contemporary standards of decency and no longer serves any legitimate penological purpose.”

What will happen in the next 48 hours in Oklahoma? I sure do not pretend to know.

But somehow it seems odd that Glossip’s best remaining chance at life is tethered to a popular former politician and an extremely popular former football coach putting enough public pressure on a sitting governor to make her change her mind.

Meanwhile, the Van Treese family remains committed to the notion that executing Glossip will provide “a sense that justice has been served.”

On the one hand, I can understand their position. Heinous crimes deserve punishment.

But on the other hand, what if there is a 4 percent chance Glossip’s execution will be the exact opposite of justice?

What if the State of Oklahoma executes an innocent man?