The Oklahoma Model Tribal Gaming Compact will become eligible for renewal or adjustment in 2020, if not earlier.

Politicians, gaming experts, bureaucrats and lobbyists have told NonDoc the state of Oklahoma is likely to seek additional “exclusivity fee” revenue from the industry, which announced Tuesday that it makes more than $4 billion in total tribal revenue each year.

“I don’t think the tribes would be surprised if the state asked for more money, particularly under the current economic climate,” said William Norman, an attorney who represents multiple tribes. “But I think what tribes are concerned about is making sure that there is accountability with respect to the funds that they are providing to the state.”

Norman spoke to NonDoc at an Oklahoma Indian Gaming Association luncheon where the association released an “impact report” showing that gaming institutions have now paid $1 billion in “exclusivity fees” to the state since the Oklahoma State-Tribal Gaming Act took effect in 2005.

Follow NonDoc:

Those fees are paid for Class Three gaming — think card games and traditional slot machines — and are calculated thusly: 4 percent of the first $10 million in net-win revenues, 5 percent of the second $10 million and 6 percent of anything above $20 million.

As an example, the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes paid the state $488,105 in FY 2015, meaning their total net-win gaming revenue was somewhere above $12.2 million. Norman said he represented the Wichita tribes, the Absentee Shawnee and others.

“Education is where they want the money spent,” Norman said. “They’ve committed to it, the state’s committed to it in the compact. So, if anything, there might be room for discussion about defining and having some accountability for where those funds go — maybe returning some of those to a more local level.”

‘We are absolutely preparing for it to come up again’

Government officials — some speaking on the condition of anonymity — confirmed there will almost certainly be a battle over renewing and/or renegotiating the compact.

“I think whoever the governor is (in 2020) would have to try to do that,” said a sitting Republican legislator. “I almost believe that the tribes know they have been doing very well. They have an exclusive agreement. We can’t put a casino in Edmond.”

Rep. Jerry McPeak (D-Warner) is an active member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. When reached by NonDoc on Wednesday, McPeak said he was sitting in a room discussing the gaming compact with two other tribal members at that very moment.

“If the sun rises in the east (in 2020), there will be action taken (on the compact),” McPeak said. “Wearing my Indian hat today, we are absolutely preparing for it to come up again.”

‘Don’t blame that on the Indians’

McPeak spoke critically of Oklahoma’s budget problems and pushed back against the notion that tribes should offer a bigger percentage of their gaming revenue to fix state problems.

“Since they have screwed up their own finances and since the tribes have been so successful — and it appears the tribes have been much better caretakers of their success — I’m sure they would like to capture more of that success for their own use,” he said. “It isn’t the tribes’ fault that the last 11 years of control of a Republican legislature has driven us into debt and an unbalanced budget (that is) funding our schools at the lowest level of any state in the union.

“Don’t blame that on the Indians, and don’t be jealous because the Indians have been successful in their business ventures.”

Very successful.

Michael Odle, director of public affairs for the National Indian Gaming Commission, said his federal agency regulates tribal gaming by region.

“We have 242 tribes across 28 states operating 450 gaming establishments,” he said. “We also conduct site visits to the individual casinos. It varies from one or two to five or six per year. They are random and not necessarily scheduled.”

He said 29 percent of the country’s Indian gaming facilities are in Kansas, Oklahoma or Texas.

“In 2014, the OKC region (including western Oklahoma and Texas) showed the largest portion of growth at about 7.5 percent, which was roughly $141 million,” Odle said. “But Tulsa was no slouch either. They still had a 1.8 percent increase, which was nearly $38 million. So we’re seeing a lot of growth in that region.”

Regulatory rigmarole

All of that gaming is mostly regulated in two ways: self-regulation from tribes’ individual gaming counsels, and NIGC oversight.

The state of Oklahoma, however, does have a Gaming Compliance Unit under the Office of Management and Enterprise Services, but some people believe it is understaffed considering the magnitude of state casinos paying exclusivity fees on a monthly basis.

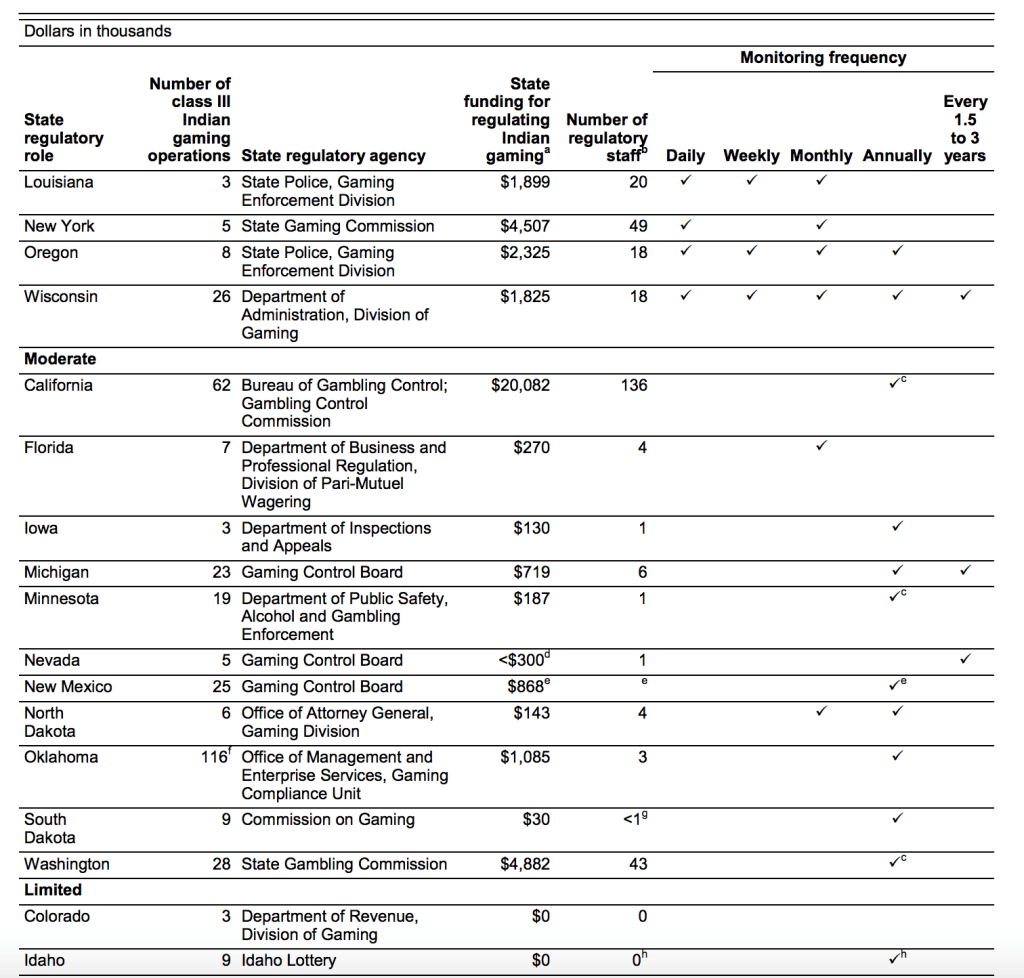

“When you look at other states, they have larger gaming-compliance divisions than we do,” said Preston Doerflinger, Oklahoma secretary of finance and revenue.

Indeed, while Doerflinger’s agency has only three staff members dedicated to gaming compliance for more than 100 casinos, Wisconsin has 18 people for 26 casinos. Michigan has six people for 23.

Norman and other people with ties to tribal gaming argue a superlative that is hard to prove or disprove: that tribal gaming is “one of the most highly regulated industries in America.”

“The regulatory environment we have right now is by design. We actually talked about this when we negotiated the compact,” he said. “The tribes have regulated gaming for over a decade. The state was brand new to it. They didn’t understand the regulation, so we were in a little different position than other states because we had the understanding, we had the education, we had the experience, and the state said, ‘Well, we appreciate that and we’re not going to try to expend a lot of effort to create a new bureaucracy to do that.’”

‘Steak, steak, roulette’

Norman also said that, moving forward, tribes would like to have more certainty that fees paid to Oklahoma are being used accountably to fund education, as the compact notes. He said that is the case whether the base fee rate remains at 4 percent or is pushed for a raise.

Lucian Tiger, a tribal council member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, minced fewer words.

“We would like to know as a Nation where our gaming revenue that is going to the state is going,” Tiger said. “Because those dollars cannot be going where they’re supposed to [if] our schools and education system are in the condition they are in.

“How were the schools funded before the gaming monies?”

McPeak, who was first elected when the gaming compact took effect in 2005, reflected on the notion that tribes are now being defined in Oklahoma by gaming wealth.

“When I was a little kid, they would say things — that didn’t hurt me — but they’d say, ‘How do you speak Creek Indian?’ They’d say, ‘Cheese, cheese, bingo.’ Well, that might have been a slam,” McPeak said. “No one says that now. They would say, ‘Steak, steak roulette,’ maybe. So if you think that Indians are going to feel bad about moving from cheese to steak or bingo to roulette, I think that would be a misnomer.”

Tiger said he thinks increasing the exclusivity fees is an unlikely outcome.

“Why would the tribes want to do that?” he asked. “In my opinion, the tribes just want to be left alone.”