The Oklahoma Board of Corrections heard a 90-minute staff presentation Tuesday that described a state corrections crisis defined by enormous financial and operational challenges.

Beyond dozens of grim statistics concerning Oklahoma’s overcrowded prison system, board members heard tangible examples of a struggling institution: broken air conditioning systems; unmet mental health care needs; a prison water tower full of holes plugged by a mop handle and a toothbrush.

“At some point in time, somebody is going to have to step up,” Mack Alford Correctional Center warden Kameron Harvanek told the board, despite a staff member ushering him from the podium owing to time constraints for the presentation.

Harvanek, who said his prison features the precarious water tower, received applause from the 40 or so people who attended Tuesday’s meeting at the Kate Barnard Community Corrections Center in northeast OKC.

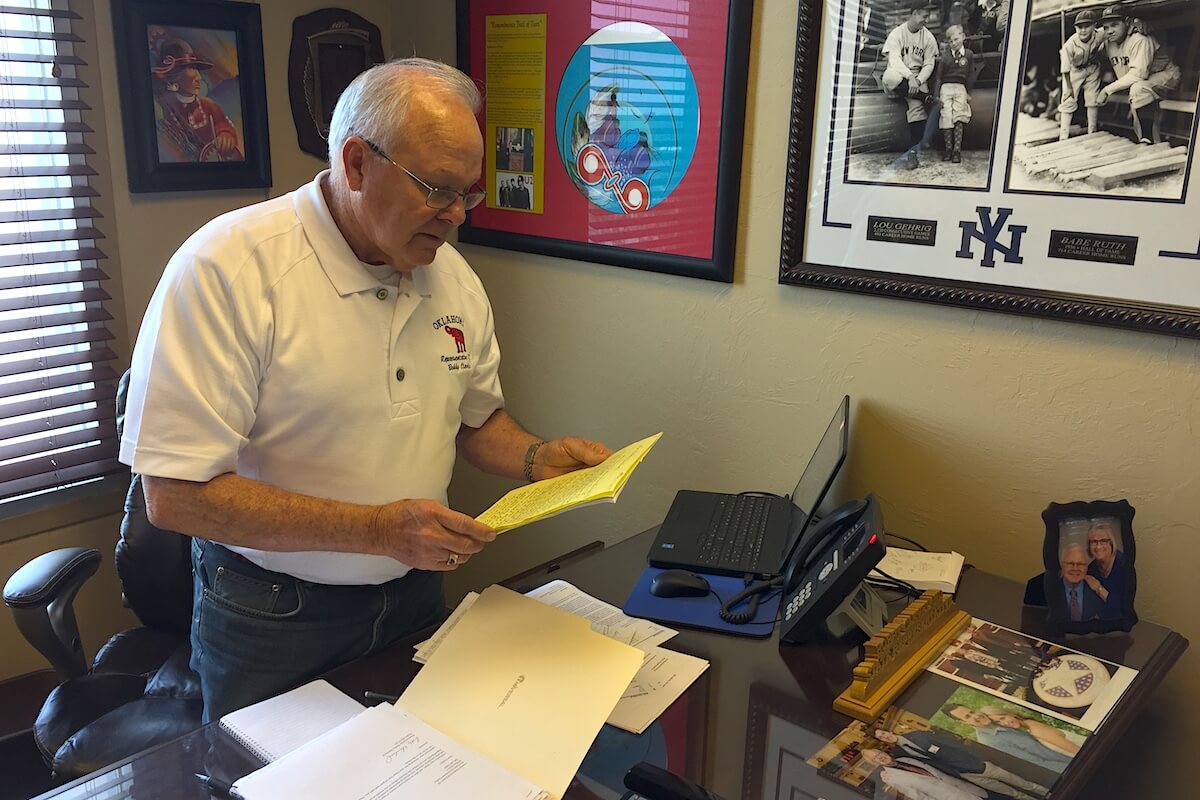

One of those people — and the only state lawmaker in attendance — was Rep. Bobby Cleveland (R-Slaughterville).

“Everything I heard was accurate. I didn’t think anything was exaggerated. Our prison system is in a terrible, terrible condition, and we’ve got to do something,” said Cleveland, who has made dozens of visits to prisons in recent years. “The people of Oklahoma have got to wake up. They’ve got to understand. It takes everybody. They’ve got to be calling up there at the Capitol and demanding something has to be done. We cannot continue like we’re doing right now.”

Corrections crisis: ‘It’s a story that tells itself’

Cleveland has been a harsh critic of the state’s district attorneys and powerful GOP lawmakers who stalled several criminal justice reform bills in the Legislature this year. But he was far from the only loud voice calling for change at Tuesday’s meeting.

RELATED

Criminal justice reform: ‘We’re making them meaner in prison’ by William W. Savage III

“We will continue to be out there beating the bushes and educating all the stakeholders in the criminal justice sector,” said Department of Corrections director Joe Allbaugh. “It’s a story that tells itself. We have no place to put these folks. So that you know, the 1,716 individuals in county jail backup cost us (…) $16.6 million per year.”

Allbaugh offered the board his blunt and concerned assessment after more than half-a-dozen staff members highlighted different problems the department faces. One noted a severe lack of educational programming, which is particularly exacerbated any time the agency has had to create “temporary beds” in the day areas of overcrowded prisons.

“If we’re not the Department of Corrections, what are we? The Department of Warehousing? That’s a problem,” Allbaugh said. “That’s a problem to each and every one of us in our state. That’s a problem for our elected leaders, and it’s time for them to wake up and make the tough decisions.”

Allbaugh outlined his agency’s three core functions:

- Protect the public, protect employees and protect inmates.

- Provide constitutional levels of confinement and care.

- Operate within the appropriated budget.

The former Federal Emergency Management Agency director who assumed his DOC post in early 2016 said the third function “is difficult to do.”

“I showed up about 18 months ago and feel like I inherited the Titanic that has already been ruptured,” he said. “What you’ve seen today is just the tip of the iceberg.”

‘We’re in serious danger of running out of time’

Allbaugh said the agency receives only about one-third of the money it truly needs, and he reiterated past arguments for the need to build two new medium-security prisons for male offenders and one new facility for females. Those price tags would require $1.2 billion to build and $700 million to operate, though Allbaugh implied he would rather do so than pay private prison companies to house more than 5,000 inmates annually.

“It is not our job and the Department of Corrections’s job to support the private prison industry,” Allbaugh said. “Historically, this agency has balanced the budget on the backs of our employees. As long as I’m the director, we’re not going to do that anymore.”

Staff noted that initial pay for an Oklahoma correctional officer is less than $13 per hour, which falls below that which someone could make at a 7-11 entry position.

“I know this has been a very long meeting, but it is extremely important for members of the board, the public, and for our employees to understand what is at stake,” Allbaugh said.

Board members appeared dismayed by the presentation, which they had heard previously and decided the public needed to see as well.

“I think we’re in serious danger of running out of time on this issue, and we’re going to have a major incident,” said board member Kevin Gross. “We’re all going to be challenged by that.”

Board chairman Michael Roach agreed.

“I think we’re very fortunate that there hasn’t already been an issue in one of these facilities,” he said. “I don’t know. I don’t have any idea.”

Board member Adam Luck felt similarly.

“What do we do? If the only answer is letting people out on the back end, somehow that doesn’t seem good enough,” Luck said. “I hope people begin to understand the implications of what their elected officials are choosing to do during the legislative session.”